In late 1774 or early 1775, a woman named Jeanne Baret became the first woman to have circumnavigated the globe, landing in France after nearly a decade of global travel that took her from provincial France to places like Tierra del Fuego, Tahiti, and Mauritius. Her story, a fellow traveler noted, should “be included in a history of famous women.”

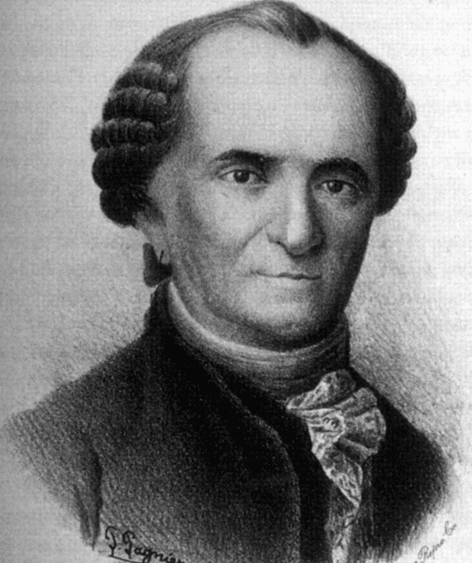

Jeanne Baret had been born in the town of Autun in 1740 to a father was a day laborer, so she grew up poor in a rural area where her family would have worked for the local landlords in the fields. In this environment, Baret became an herb woman, an expert at identifying, gathering, and preparing useful plants to cure illnesses. Her work led her to  meet Philibert Commerson, a naturalist, who relied on her expertise for his own projects and who took her to Paris as his aide and mistress. Baret’s story is fraught with intrigue and deception. She accompanied Commerson around the world on the famous expedition of Antoine de Bougainville, but only by disguising herself as a man. Commerson and Baret collaborated on this endeavor: Commerson left behind a misleading will that named Baret as Commerson’s heir if he died to conceal their journey together.

meet Philibert Commerson, a naturalist, who relied on her expertise for his own projects and who took her to Paris as his aide and mistress. Baret’s story is fraught with intrigue and deception. She accompanied Commerson around the world on the famous expedition of Antoine de Bougainville, but only by disguising herself as a man. Commerson and Baret collaborated on this endeavor: Commerson left behind a misleading will that named Baret as Commerson’s heir if he died to conceal their journey together.

In the late eighteenth century, the French government sent many naturalists like Commerson to the South America, Madagascar, and Indonesia in search of spices and useful plants to be cultivated by enslaved Africans working on plantations in their overseas colonies. Sugar and coffee had already been established as cash crops in colonies like Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), so a new wave of explorers and scientists sought other plants to replicate these successes. In the Indian Ocean, French botanists and colonial leaders sought to transplant spices from the East Indies onto their own colonies of Mauritius and Réunion, undercutting the Dutch spice trade. Baret’s expeditions were part of a global scientific endeavor designed to cultivate profitable commodities like pepper and coffee in order to strengthen the French imperial economy. However, Baret’s story also shows that this wider project was carried out by individuals who applied local knowledge and experience, gleaned from days spent in French fields and forests, to new and uncertain environments many miles away from home.

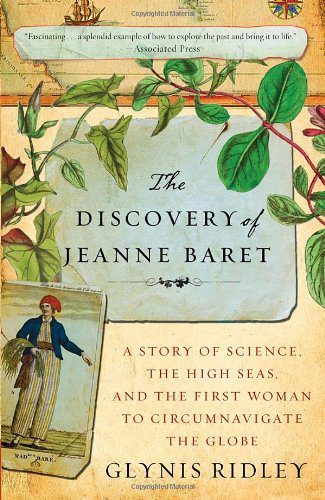

Several journals by members of the Bougainville expedition have survived. They described a variety of supporting characters: the conniving surgeon Vivès (Commerson’s rival and Baret’s possible rapist), the androgynous Prince of Nassau-Siegen, clad in a velvet robe and high-heeled slippers, and Aotourou, the Tahitian who publicly acknowledged Baret as a woman and later accompanied Bougainville back to France. The author of this book about Baret, Glynis Ridley, notes a surprising lack of information about Baret in these journals. The Étoile’s close quarters and long voyage make it difficult to imagine that Baret’s secret could have been kept for long, but only one journalist, the antagonistic surgeon Vivès, mentioned her before the landing in Tahiti.

Several journals by members of the Bougainville expedition have survived. They described a variety of supporting characters: the conniving surgeon Vivès (Commerson’s rival and Baret’s possible rapist), the androgynous Prince of Nassau-Siegen, clad in a velvet robe and high-heeled slippers, and Aotourou, the Tahitian who publicly acknowledged Baret as a woman and later accompanied Bougainville back to France. The author of this book about Baret, Glynis Ridley, notes a surprising lack of information about Baret in these journals. The Étoile’s close quarters and long voyage make it difficult to imagine that Baret’s secret could have been kept for long, but only one journalist, the antagonistic surgeon Vivès, mentioned her before the landing in Tahiti.

In places where the historical trail is broken, Ridley provides plausible speculations. Why did Jeanne Baret sign up to go on the expedition? Without Commerson’s support, Baret lacked a home and an income (she worked as his housekeeper officially). Who first recognized Jeanne Baret as a woman? The official story was that the Tahitian chief Aotourou identified her as a cross-dresser, though Vivès’s diary makes it clear that several crew members suspected that she was a woman much sooner. Most likely, some people realized that Jean was, in fact, Jeanne, but knew that to expose her would invite a violent assault on her. Bougainville determinedly relegated Baret’s discovery to a page, refusing to acknowledge it as more than a passing incident, but Ridley insists that she was gang raped by crew members on the island of New Ireland in the South Pacific in 1768.

Like other early modern French women, Jeanne Baret lived in a society in which men wielded considerable power and women were frequently excluded from historical records. Capable as a botanist, but most likely illiterate, Baret’s story has been preserved through the testimony of men like Commerson and Bougainville who wrote about her alongside journal entries about navigation and botany, though she did leave one manuscript list of medicinal plants behind. Though Baret’s discoveries were noted by the designation of a genus named Baretia, it was later renamed so that now only plants discovered by Commerson remain acknowledged by taxonomy. To understand Baret’s life thus requires readers to follow the complicated and treacherous path she took herself and that Ridley has painstakingly reconstructed.

Louis Antoine de Bougainville’s frigate

Ridley excels at linking together historical evidence to tell Baret’s story through the imagined eyes of Jeanne Baret. The travel journals of Vivès, Commerson, and others are supplemented with information about the geography and politics of the places and people Baret encountered. Ridley weaves together a narrative of Baret’s journey with fascinating tidbits about scientific discoveries like beaked dolphins and the Bougainvillea—a plant that Ridley argues was, in fact, discovered by Baret herself. Fans of travel literature and science writing will appreciate this story, for the description and detail of Baret’s experiences in places like Rio de Janeiro and Tahiti, as well as the many plants and animals she encountered. Readers interested in the history of women will likewise appreciate the way Baret’s story illuminates the opportunities and challenges faced by European women in the eighteenth century.

Photo credits:

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons