Dulcinea in the Factory presents a gendered historical analysis of the boom in the textiles industry in Medellín that goes beyond the typical economic analysis of industry-based modernity. It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as Don Quixotes protecting fragile, virginal Dulcineas –their female employees. However, as Farnsworth-Alvear reveals, the real Dulcineas, the mujeres obreras (working women) found clever ways of coping with such fervent guardianship.

It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as Don Quixotes protecting fragile, virginal Dulcineas –their female employees. However, as Farnsworth-Alvear reveals, the real Dulcineas, the mujeres obreras (working women) found clever ways of coping with such fervent guardianship.

Farnsworth-Alvear offers a synopsis of the evolution of industrial work in Medellín by examining the modernizing projects pushed by the technocrat elites who established the first textile factories. As the title implies, this industrial project was an experiment that merged modernity and religion on the factory floor. Housing, recreational facilities, and company-sponsored activities simultaneously monopolized control and granted factory owners opportunities for public display of their protective and affectionate nature toward the female workforce. In the same vein, Catholic rhetoric depicting a vulnerable, virginal, working woman influenced factory guidelines aimed at protecting women from arduous factory work and sexually precarious situations. As the author emphasizes, the close relationship between the factory and religious rhetoric is an important component to consider when evaluating the shifts in factory policy in Medellín.

Yet, these imaginary threats to chastity, painted by the church and reinforced by factory rules, were often challenged by those women who did not consider themselves in need of protection. The author’s interviews reveal that some women were far from afraid of their workingmen counterparts and they often spoke out defending themselves in a variety of ways. Farnsworth-Alvear brilliantly utilizes a combination of statistical sources and oral history that together reveal the ideologies, challenges, and lived experiences of the workers. Oral interviews uncover the secret ways in which both women and men obstructed severe factory regimens: courtships, secret marriages, pregnancies, and even abortions occurred under this strict paternalism.

By focusing on gender relations and by comparing statistical and archival material with interviews of workers, the book offers a rich history of labor, gender, and class relations in Medellín. What emerges in Dulcinea in the Factory illuminates the experiences of those involved in the Medellín modernizing project. For sixty years, workers – whatever their gender and social stratum – had significant power in negotiating their own fate. This book offers an important contribution to the study of labor and gender. More importantly, it effectively incorporates the often-neglected social and cultural component into our understanding of industrial modernity.

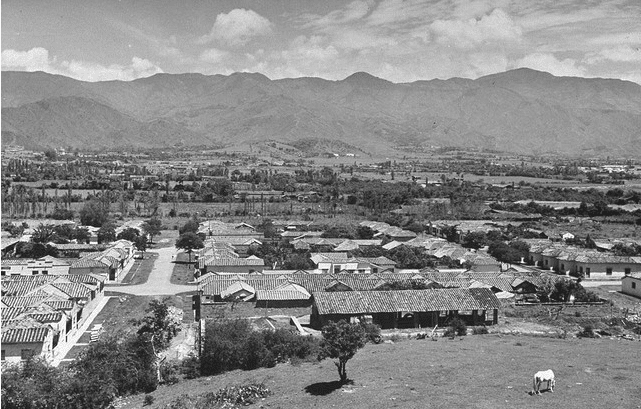

Photo credits:

Dmitri Kessel, “Overhead view of housing project for workers,” Medellin, Colombia, July 1947

LIFE Magazine via Flickr Creative Commons

Dmitri Kessel, “Worker sorting leaves in a tobacco factory,” Medellin, Colombia, July 1947

LIFE Magazine via Flickr Creative Commons

You may also like:

Michelle Reeves’ review of Hal Brands’ Latin America’s Cold War.