From the Editors: From There to Here is a new series for Not Even Past in 2021. It builds off a past initiative but expands its focus to document the journeys taken by individual graduate students to Garrison hall and the University of Texas at Austin. Gwendolyn Lockman, who is completing her PhD in History, shares her story with us. For more about Gwendolyn, see her spotlight here.

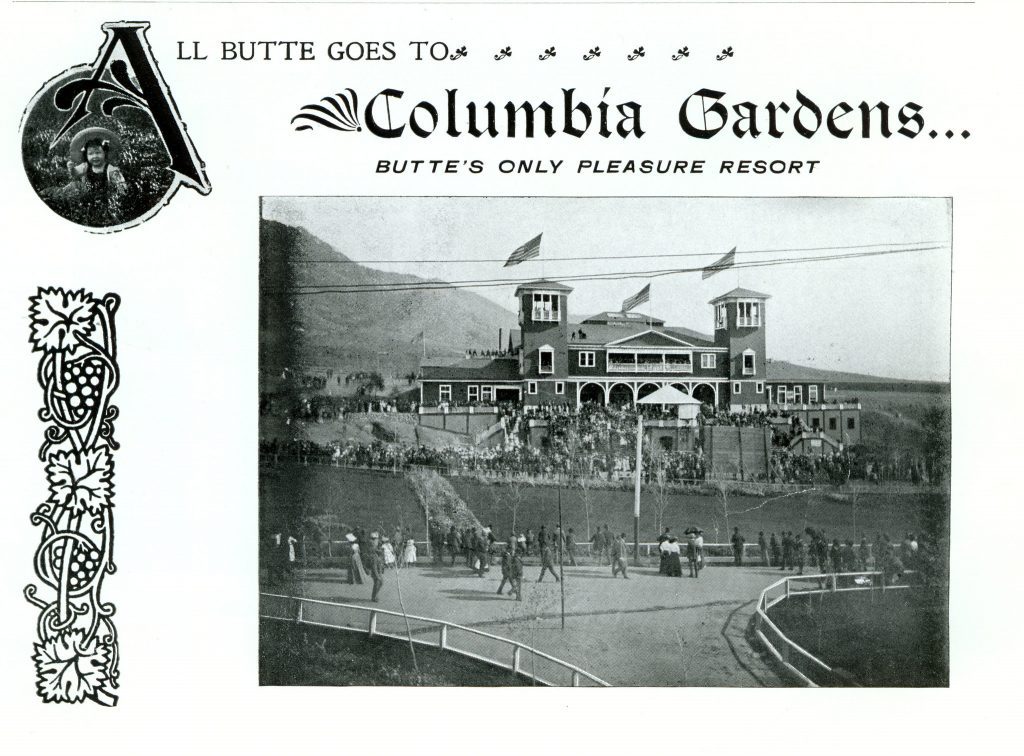

It took one visit to the Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives to fall in love. The archives are in historic firehouse No. 1 on Quartz Street in Butte, the copper metropolis that brought my maternal ancestors to Montana from Ireland, Slovenia, Utah, and Michigan. I decided my experience in the sports industry, prior to grad school, gave me enough background to work on the history of Butte’s amusement park, Columbia Gardens. The park was popularized by copper king William Andrews Clark in the late nineteenth century and maintained by the Anaconda Company after Clark’s death. After nearly a century as one of Butte’s central cultural institutions, the Anaconda Company shut down the Gardens in September 1973 to expand open-pit mining. The pavilion burned down in November of that year.

I asked my relatives about their memories of the park, which they visited for generations, but I did not see this project as what is sometimes described as “me-search.” I am motivated by the history of the park and its role in the relationships between capital and labor, between mining and the environment. In fact, I thought the project had no connection to my ancestors, until newspaper research on the Gardens revealed a long-disappeared great-great-grandfather.

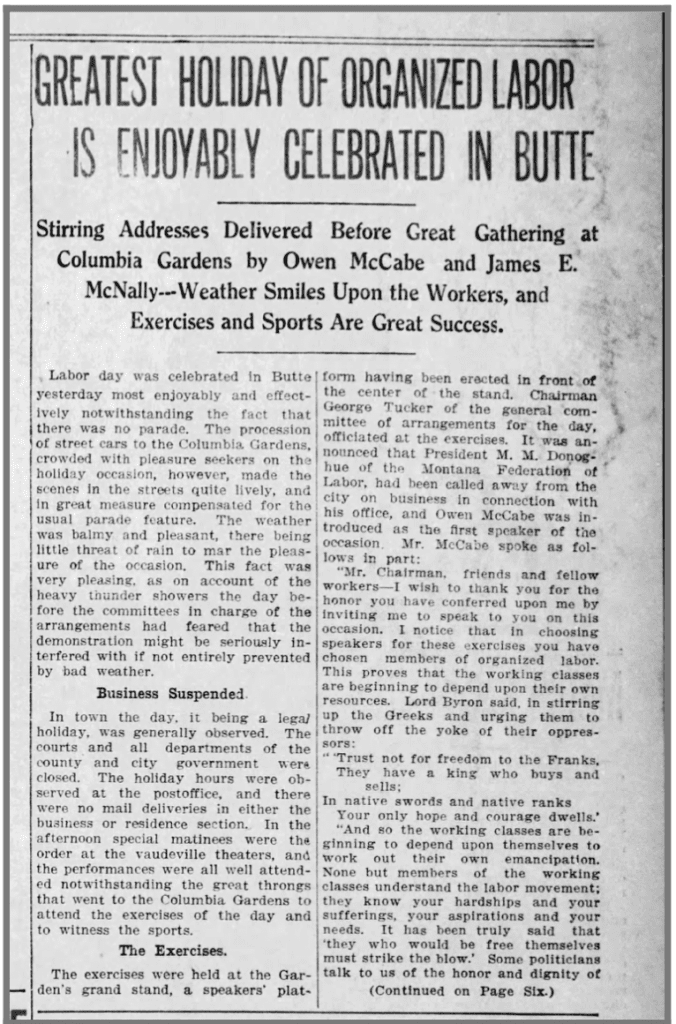

Owen McCabe was a candidate for president of Local No. 1 of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) when he gave a speech on the history of organized labor in the United States for Butte’s Labor Day 1909 celebrations at Columbia Gardens. The WFM election occurred the next day: Owen came in third.

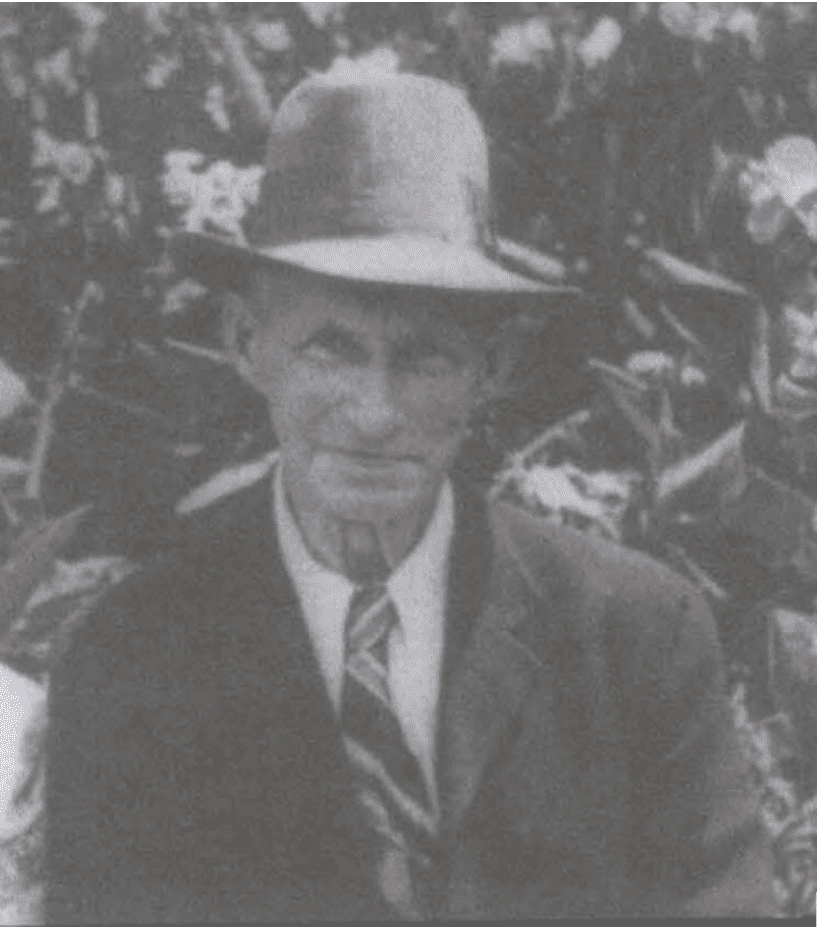

Owen was my mother’s mother’s father’s father. He was born in County Monaghan, Ireland in March 1873. He immigrated to the United States in the 1890s and settled in Montana. In May 1896, he married Nora Reid, another Irish immigrant to Montana, at St. Paul’s Church in Anaconda, the smeltertown which processed the ore from the Butte mines. Owen and Nora lived in Anaconda, north of Butte in Walkerville, and in Ronan, on the Flathead Indian Reservation, where they homesteaded. Nora and Owen had seven children: Patrick, Joseph, Victor, Mary, John, Frank, and Nora.

Owen was entrepreneurial, charming, intelligent, and fiercely principled. He mined and homesteaded, somehow earning enough money to make multiple return visits to Ireland. He adamantly opposed unbridled corporate power. We have one of his notebooks, in which he copied down labor speeches and songs, and wrote drafts of his own speeches.

Owen’s disappearance is intriguing even now. He left behind Nora and seven children in 1915, though Patrick died that November. Owen sold off all the equipment he had on the homestead in Ronan in March 1915. Someone, likely Owen, posted in the Ravalli Republic newspaper that Mrs. McCabe and her children were leaving for Canada, where they would join Mr. McCabe to live there permanently. Nora and the children never went to Canada. It is likely Owen paid for the notice about moving to Canada and left the family shortly thereafter, regardless of whether Canada was ever a part of his plans.

My great-grandfather, Frank McCabe, was about three years old when his father disappeared. Frank looked for Owen for decades. Nora insisted he was dead, but Frank never believed it. He drove my grandmother and great-grandmother to a remote Nevada mining town where he thought he had traced his father. Owen was not there, alive or dead.

Through recent DNA testing, we found out we were related to a family in New Zealand. Their patriarch, Thomas James Smith, came from Ireland by way of the United States, where he mined copper in Montana. The Smith’s photos of Thomas were unmistakably Owen. They struggled to trace their genealogy back to Ireland but knew that Thomas Smith was probably an assumed name. The mining bosses chased Thomas out of the U.S. because of his union activity. Owen was probably a wobbly, a member of the radical Industrial Workers of the World (I say “probably” because I have not yet confirmed this in the historical record), in addition to a WFM member. Butte’s most infamous lynching took place in 1917, roughly two years after Owen’s disappearance, when parties unknown violently murdered IWW organizer Frank Little. Owen may have left the U.S. to avoid a similar fate.

When I take a break from combing through city planning documents, maps, reports, photographs, and journals, I dig around looking for Owen and my other family members. I spend a lot of time walking historic uptown Butte and thinking about Owen. Until 1914, the Butte Miner’s Union Hall was at 317 North Main Street, around the corner from the Archives today. An explosion destroyed the Union Hall during the fracas of an intra-union fight. My apartment looks out on the Hennessy Building, the former headquarters of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. One ancestor organized against the Company, while another–my great-grandfather, Thomas Arthur Ryan–worked on the sixth floor of the Hennessy as an ACM Co. purchasing agent. He, too, walked these same streets when he got off the Butte, Anaconda & Pacific Railway from Anaconda to come to work. My great-grandmother Mary McCabe (née Bolkovatz) came to Butte from Anaconda to attend the Butte Business College, studying to become a personal secretary. My grandfather and many generations of uncles worked the Anaconda Smelter, processing the ore pulled from the Butte hill.

After work at the archives, I often drive the 26 miles to Anaconda, wishing the train still ran. I think about the land, the millions of years ago the Rocky Mountains formed, the people who inhabited it prior to European settlement, the immigrants who came looking for work. I visited great-grandmothers and great-great aunts and uncles in Anaconda growing up. I attended many funerals at St. Peter’s Church (St. Paul’s is gone) and Mount Olivet Cemetery, the “new” cemetery. I realized this spring that I didn’t know where Nora’s grave was. My family knew we had ancestors in one of the “old cemeteries” in the foothills above Anaconda. I searched by foot until I found them in Mount Carmel, the Catholic cemetery. One family plot includes Nora McCabe, her brothers Thomas and Michael Reid, and Nora’s children Mary, Patrick, and Victor. The Reids and McCabes are buried within 50 yards of relatives through the other side of my mother’s family: my great-great-great-great-grandfather James Ryan, my great-great-great-grandparents Thomas and Mary Ryan, and their daughters, Margret and Geraldine, who died as children. Another fifty yards to the north are my great-great-grandparents Laura and Timothy Ryan, Timothy’s brother, Emmett Joseph, and Laura and Timothy’s son, Timothy Jr.

My friends and colleagues know I am proud of my Montana roots. I feel even more connected to this place as I think of these ancestors as I walk Butte and Anaconda, as I dig through the histories of these places and my family. My dissertation is not about them, but it led me to them.

Gwendolyn Lockman is a Ph.D. candidate in U.S. History. Her dissertation project, “Recreation and Reclamation: Parks, Mining, and Community in Butte, Montana,” investigates the history of outdoor leisure spaces, union identity, and environmental health in an industrial copper mining city. Her work is supported by the Carrie Johnson Fellowship, the Charles Redd Fellowship in Western American History, the Mining History Association Research Grant, and Dumbarton Oaks through the Garden and Landscape Studies Workshop, part of the Mellon Initiative in Urban Landscape Studies. At UT, Gwen is an affiliate of the Center for Sports Communication and Media in the Moody College of Communication, completed a Women’s and Gender studies portfolio, and has contributed to the History Department as a co-leader of the Symposium on Gender, History, and Sexuality, social media manager, History Graduate Student Council Representative, and web news assistant. She earned her MA in History at UT in 2020. Before graduate school, Gwen worked in the legal department for the Washington Nationals. She earned her BA in American Studies from Georgetown University. She is originally from Poplar, Montana, and calls Missoula, Montana home.

Banner Image: Quartz Street Fire Station, Butte, Montana (1901), from Souvenir history of the Butte Fire Department by Peter Sanger, Chief Engineer

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.