From the Editors: From There to Here is a new series for Not Even Past in 2021. It builds off a past initiative but expands its focus to document the journeys taken by individual graduate students to Garrison hall and the University of Texas at Austin. In this powerful first article in the series, Ilan Palacios Avineri, who is completing his PhD in History, shares his story with us. For more about Ilan, see his spotlight here.

My Guatemalan father was born in the middle of a civil war. His childhood house was built from corrugated metal and adobe brick. He grew up clinging to my abuela’s back wrapped in a blanket as she weaved to sustain the family. He did not have shoes until he was 8 years old. He dropped out of school after the second grade. Before he reached my age, he was nearly murdered by the army three times. He worked as a trench digger and then as a laborer before fleeing his home in Huehuetenango.

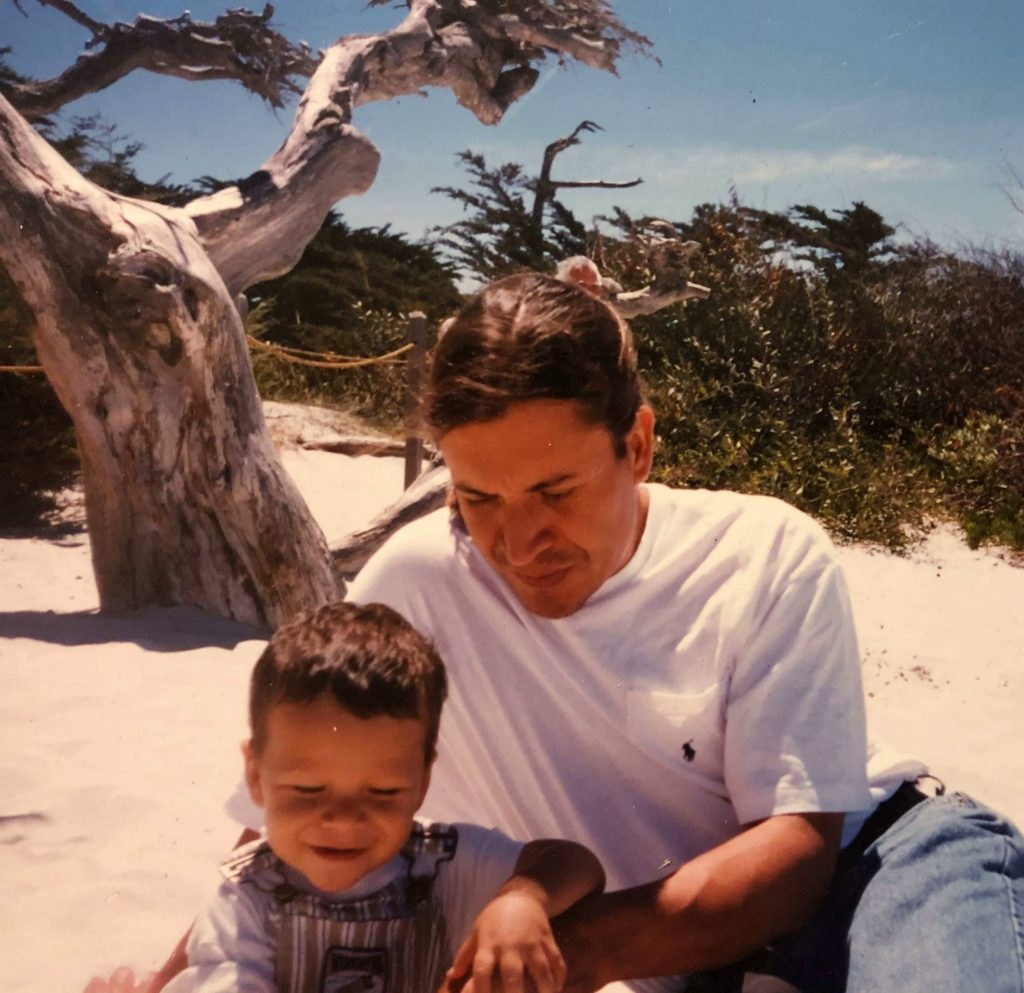

When I was a kid growing up in Los Angeles, my father never told us this history. Instead, I occasionally followed this familiar stranger to work and watched him demolish drywall. He would hold his sledgehammer tightly and swing with precision. His hands would often bruise, scab, or scar. We would break for tamales and he would make me promise never to do construction. He would then quietly return to demolition. Even so, I would watch his body as though it were my own.

Our collective forgetting continued until I arrived at university. There I finally uncovered a usable past. I found books about the dispossession and militarization of his country. I read that the Guatemalan army routinely monitored, terrorized, and murdered people in Huehuetenango with impunity. I learned that they did so with the support of the United States, the country whose flag I was compelled to pledge allegiance to as a child. And I learned how people in Guatemala resisted in ways both small and large.

I returned to Los Angeles and started speaking to my father’s silences. He began unearthing the stories of his war. He trusted me with the memories etched in his skin, the trauma buried between his bones. He recalled the fear he felt when soldiers placed a muzzle to his back. He described being extorted by the Mexican police on his way to the US. This familial unforgetting was deeply painful and, at the same time, sustaining. Our lack of funds, our family’s struggles, our very condition was given cause. Our collective shame dissolved in the process. The dialogue set us free.

Through these conversations, I learned that love, justice, and understanding were one and the same. Each could only be realized when suffering was allowed to speak. Speaking truth required listeners. I arrived at UT, principally, to hear the histories of Central Americans. To listen to stories not only of suffering and despair, but of joy, happiness, and triumph. To participate in the healing dialectic.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.