by Benjamin Griffin

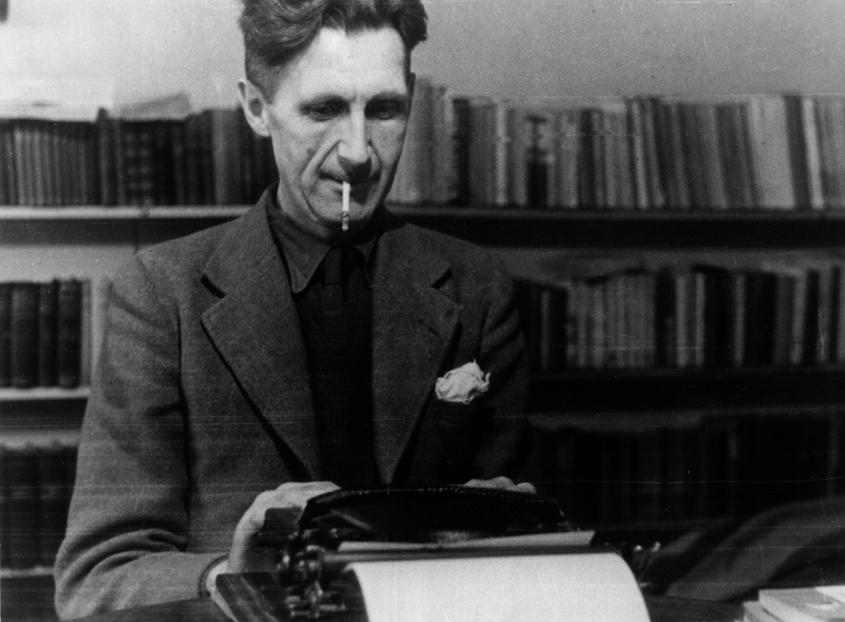

Peter Davison’s careful selection and annotation of George Orwell’s personal correspondence in provides an engrossing autobiography of a man whose work continues to resonate globally in significant ways.  A Life in Letters covers the breadth of Orwell’s life and provides an intimate and detailed look at his personality, influences, and beliefs. Davison is enormously successful in allowing the letters to improve our understanding of a broadly misunderstood man and to tell the story of a truly remarkable life.

A Life in Letters covers the breadth of Orwell’s life and provides an intimate and detailed look at his personality, influences, and beliefs. Davison is enormously successful in allowing the letters to improve our understanding of a broadly misunderstood man and to tell the story of a truly remarkable life.

Orwell’s letters are of particular value in depicting the changing way the world defined communism and socialism. Orwell’s dispatches from Spain show his personal, if accidental, involvement in the battle between Stalin and Trotsky. The ideological purge of the International Brigade forced him to depart Spain or face execution by Soviet proxies. Upon return, his letters demonstrate frustration with the refusal of traditional socialist journals to publish his works due to this perceived ideological taint. Later, Orwell finds he is unable to publish Animal Farm during World War II in part due to the British desire to maintain the positive image of Stalin and the Soviet Union, who were allies against Hitler. Despite finding success with Animal Farm and 1984, his letters also reveal a frustration with those who feel he is defending the status quo of western life, which is a perception of his work that still exists. Orwell claims that these people are “pessimistic and assume that there is no alternative except dictatorship or laissez-faire capitalism.” Elements of Orwell’s alternative democratic socialism are scattered throughout his correspondence, and the reader comes away from A Life in Letters with a good sense of how Orwell defined the responsibilities of government. Orwell’s letters reinforce his other writings that advocate political reform to eliminate class-based inequalities, such as access to education and medical care, while still guaranteeing individual freedoms.

Throughout the letters the mundane sits in close proximity to the profound. A notable example comes in a letter to working-class novelist Jack Common, in which Orwell first advises him on the proper thickness of toilet paper for use at Orwell’s country home before delving into a withering criticism of the “utter ignorance” of left wing intellectuals who believed they could use the upcoming Second World War to start a violent revolution in Britain. It is the mundane details that reveal Orwell’s personality. He was generous to friends and strangers alike, but was generally pessimistic about himself, his writing, and the future, and his chauvinism destroyed several friendships. Contrasts like these serve to humanize Orwell, and separate the man from the prophet.

Davison works diligently throughout A Life in Letters to ensure that the reader never loses track of the context in which Orwell wrote. Many of Orwell’s letters are indecipherable without Davison’s frequent and detailed footnotes identifying literary references, personal connections, and world events. Likewise, the inclusion of brief biographies of recipients in the bibliographical summary illuminates the broad variety of people with whom Orwell corresponded. The division of Orwell’s life into eight eras, and inclusion of a brief overview ahead of each part also helps shape the readers focus and makes finding specific letters easy. The main flaw in A Life of Letters is one of repetition. Davison often includes multiple letters from a brief period which contain the same content. There is also little correspondence from Orwell’s time in Burma, a key period in the development of his anti-imperialism. Whether this is due to a lack of available content or editorial decision is unclear.

Orwell’s writing in letters is as thoughtful and enjoyable as his prose. They show Orwell as unwilling to merely comment on the injustice he sees and his focus on tangible actions keeps the readers’ interest as easily as any thriller. The result is a detailed and intimate account that touches on the defining issues of international relations in the twentieth century and questions on the role of the state which remain topics of intense debate.

Photo Credits:

1950s dustcover for George Orwell’s 1945 novel, Animal Farm (Image courtesy of Michael Sporn Animation)

Orwell at his typewriter (Image courtesy of Getty Images)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines

***

You may also like: