by Christopher Dietrich

Occupy Wall Street has captured national attention for over a month now. In fact, the durable energy of the movement—which has cropped up across the country, including here in Austin—has led some media outlets to argue that it is the most important left-of-center movement of its type since the 1960s.  Commentators from the New York Times’ Paul Krugman to the Daily Show’s Jon Stewart have even compared Occupy Wall Street to the Tea Party, a comparison both groups are sure to shudder at, but one that is valid nonetheless, given the growing public profile of Occupy groups, especially with the success of the “global day of Occupation” on October 15.

Commentators from the New York Times’ Paul Krugman to the Daily Show’s Jon Stewart have even compared Occupy Wall Street to the Tea Party, a comparison both groups are sure to shudder at, but one that is valid nonetheless, given the growing public profile of Occupy groups, especially with the success of the “global day of Occupation” on October 15.

For historians who have commented publicly on the movement, the central question has been whether Occupy Wall Street will have legs. One measure of this may be whether Occupy Wall Street remains atop The History News Network’s “Hot Topics” list. For most historians, the history of dissent and protest has framed this discussion. If academic humanists filled the liberal stereotype into which they are often shoe-horned, one would expect uniform and unmitigated support for the protesters. However, a more cautious consensus has emerged.  Judith Stein, a historian at City College of New York who has visited the movement in Foley Park, expressed most clearly the liberal pessimists’ view in a magazine that, ironically, is called Dissent. “These kinds of endeavors have a long history in the United States,” Stein reminds her readers, “from the creation of utopian communities in the nineteenth century to the formation of communes in the 1960s and 1970s.” However, her point is not to celebrate Occupy Wall Street as the culmination of what came before. Rather, she warns that left-leaning movements’ “track record as a vehicle for change is poor.”

Judith Stein, a historian at City College of New York who has visited the movement in Foley Park, expressed most clearly the liberal pessimists’ view in a magazine that, ironically, is called Dissent. “These kinds of endeavors have a long history in the United States,” Stein reminds her readers, “from the creation of utopian communities in the nineteenth century to the formation of communes in the 1960s and 1970s.” However, her point is not to celebrate Occupy Wall Street as the culmination of what came before. Rather, she warns that left-leaning movements’ “track record as a vehicle for change is poor.”

The editor of Dissent, the historian of the left Michael Kazin, said as much in a recent editorial in The New York Times. “Stern critics of corporate power and government cutbacks,” Kazin believes, “have failed to organize a serious movement against the people and policies that bungled the United States into recession.” Although Occupy Wall Street could dovetail with the demonstrations that roiled Wisconsin earlier in the year, Kazin’s message of warning is as clear as Stein’s. Using a set of historical analogies—the link between the Gilded Age and the rise of organized labor in the 1930s and the link between the proto-conservative movement of the 1970s and the Tea Party—Kazin worries that today’s movements on the left lack the institutional strength to “articulate and fight for the vision of a more egalitarian society.”

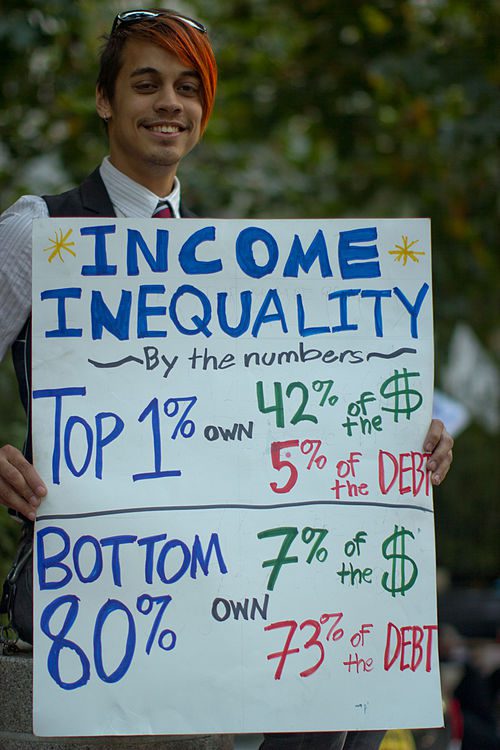

It would be foolish to describe Kazin and Stein’s warnings as cynical. Still some scholars, notably two from a younger generation, seem more optimistic about Occupy Wall Street, though they share the same concerns. In an interview with American Public Media’s Market Place, University of Texas historian Jeremi Suri told Kai Ryssdal, “Unfortunately they’re not offering any cohesive or coherent alternative to the capitalist system as we know it.” However, Suri ended on an optimistic note: “Give them some time.” On NPR’s All Things Considered, Yale historian Beverly Gage also began by noting the lack of coherence in the movement’s message. Historically, “lots of different sorts of people” have been involved in protests, Gage said, “and they haven’t always necessarily gotten together.” Still, like Suri, Gage prefers to look at the possibilities presented by the movement’s momentum. “They’ve pressed questions about inequality, about the role of Wall Street and finance in the American economy, and just big moral questions about what do we want out of our society,” she said.

It would be foolish to describe Kazin and Stein’s warnings as cynical. Still some scholars, notably two from a younger generation, seem more optimistic about Occupy Wall Street, though they share the same concerns. In an interview with American Public Media’s Market Place, University of Texas historian Jeremi Suri told Kai Ryssdal, “Unfortunately they’re not offering any cohesive or coherent alternative to the capitalist system as we know it.” However, Suri ended on an optimistic note: “Give them some time.” On NPR’s All Things Considered, Yale historian Beverly Gage also began by noting the lack of coherence in the movement’s message. Historically, “lots of different sorts of people” have been involved in protests, Gage said, “and they haven’t always necessarily gotten together.” Still, like Suri, Gage prefers to look at the possibilities presented by the movement’s momentum. “They’ve pressed questions about inequality, about the role of Wall Street and finance in the American economy, and just big moral questions about what do we want out of our society,” she said.

Indeed, today’s movement may be similar to the shared critiques of populists, anarchists, and communists at the turn of the previous century, described in Gage’s engaging book on the 1920 bombing of the J.P.Morgan headquarters, The Day Wall Street Exploded. This is especially true in the sense that the protests both reflect a broad sense of frustration shared by much of society and represent the diversity and disjointed nature of that frustration. So, the question follows, how can Occupy Wall Street move beyond these big moral questions and provide coherence? What does history tell us?

The central thread that ties the above historical perspectives together is a warning to the new denizens of the left: if Occupy Wall Street remains disjointed, its chances of having an enduring historical legacy will be slim. At some point in the near future, the leaders of the movement must come together and present a coherent narrative for change. One step towards doing so would be the convening of an Academic Advisory Board. This would do more than lend, in a much-repeated but patronizing phrase, “intellectual heft” to the protests. More importantly, it might also help the movements’ leaders articulate their goals more clearly.

The primary organizers of the movement should realize that the risk of giving up some control of the movement weighs far less than the possibility that it could lose relevancy and slowly peter out. I’m sure the historians above, as well as other scholars who have come out in support of Occupy Wall Street—like New York University economist Joseph Stiglitz, who told protesters at a recent teach-in that they had the right to be indignant—would be happy to comply.

Photo Credits

All via Wikimedia Commons

David Shankbone, Occupy Wall Street, October 5, 2011

Crispin Semmens, Occupy London, 16 October 2011, St. Paul’s Cathedral

Victorgrigas, Sign at Occupy San Francisco, October 13, 2011