Austin’s creation of what today we call its “creative class” was made possible by developments that hived the city into two realities: A pleasant, well-groomed and very White West side, and an out-of-sight, out-of-mind East side for those who would never be in any promotional brochures

This article first appeared in Urbanitus, a new media project co-founded by Jeremi Suri. The original can be accessed here.

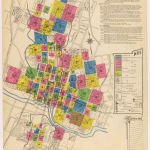

Among famous dates that defined everything that came afterward, there’s 1776 for the Declaration of Independence, 1789 for the French Revolution, 1914 for the assassination that sparked World War I, or 1989 for the collapse of communism. For Austin, that seminal moment is 1928.

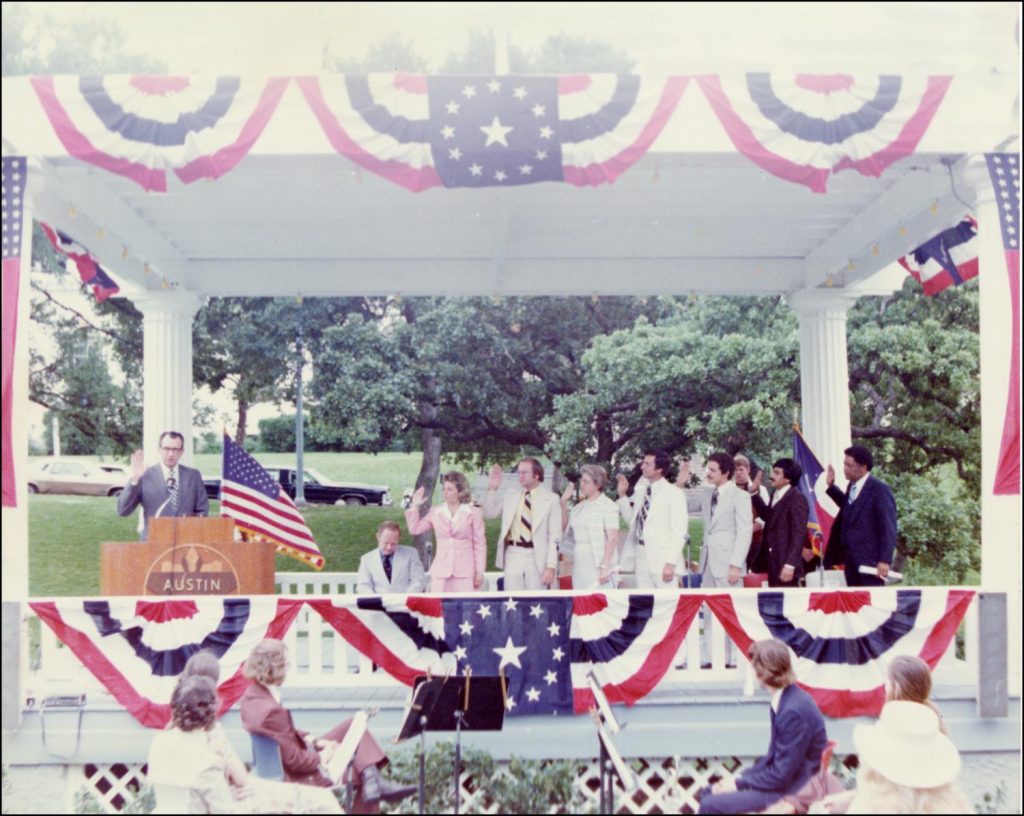

Following the character-setting City Plan in that year, Austin continued to develop as the state capital and home of Texas’ flagship university. The culture of the small city, the majority of its budget, and the employees in town were associated with either government or university. Although the economy solidified and the cultural landscape grew, the city government remained the same. The city council maintained its at-large structure, but expanded from four to six councilors plus the mayor in 1969. Austin’s city government, however, was by then already long outpaced by modernism, and many areas of town were underrepresented, if at all. As other cities — even throughout the Deep South — reformed local government to reflect the changing world throughout the Civil Rights movement to make accommodations for historically underrepresented minorities, Austin’s council remained unrepresentative of large swaths of its residents. African Americans and Latinx communities were acknowledged by incorporating a single representative in a “gentlemen’s agreement” made in the 1970s that did little to reform the Progressive Era’s open invitation for business interests and “decent” (read, White) people to dominate the government’s agenda long after civil rights legislation was passed throughout the nation.

The effects of the Progressive Era-influenced changes to Austin’s government system, which gave us the at-large council and a city manager in charge of much of the city’s executive business, outlasted the Progressive Era itself. The Progressive insistence that local government resemble an apolitical service provider endures in many cities; this is not an Austin-specific phenomenon. Motivation behind “running the city like a business,” as it’s often explained, comes from the fear of political parties dominating service provision and politics in cities, which have the potential to be anti-democratic and to inconvenience big segments of the population. In the 19th century, when these ideas were fomenting in urban politics, this fear had serious material effects. For example, reformers cut the infectious disease mortality rate by 75 percent between 1900 and 1940 due to the development of water and sewer systems, built by cities with minimal partisan patronage.

Then and now a city well run — and well segregated

Beyond breaking the patronage politics that prevented sensible development of city services, Progressive reformers were concerned with the outsized influence of political parties on city politics as well. Parties are national organizations that have state and local offices. In the 19th century, even the people at the top of the parties, U.S. presidents, used patronage to install friendly local administrators and ensure partisan influence in local operations with post offices. During the Progressive Era, counties where the president’s party led in politics got more post offices than others. It may not sound like a big deal in the era of email and 5G internet, but in the 1800s post offices were a vital institution, the lifeline to the outside world. Reformers sought to change the political system, dependent on patronage. But, their sentiment for good governance did little to provide services to the poor or communities of color themselves. It was still mostly about party influence and corruption of individuals.

Urban problems like segregation and later, gentrification, are not unique to Austin of course, but they have been unusually far from the civic mind of a city priding itself as a model. And despite persistent problems like segregation’s lingering influence, the city has always been efficient and well run by the standards of those in charge. The at-large council and manager system that was created early in the 20th century really set the stage for Austin’s progressive reputation. At the end of World War II, the city government began to recognize that along with that reputation its potential comparative advantage resided in what was soon to be known as the burgeoning knowledge economy. For this was the era that birthed “The Bomb,” a Cold War moment when science, electronics and defense-related spending captured both the public imagination and the budgets of Washington.

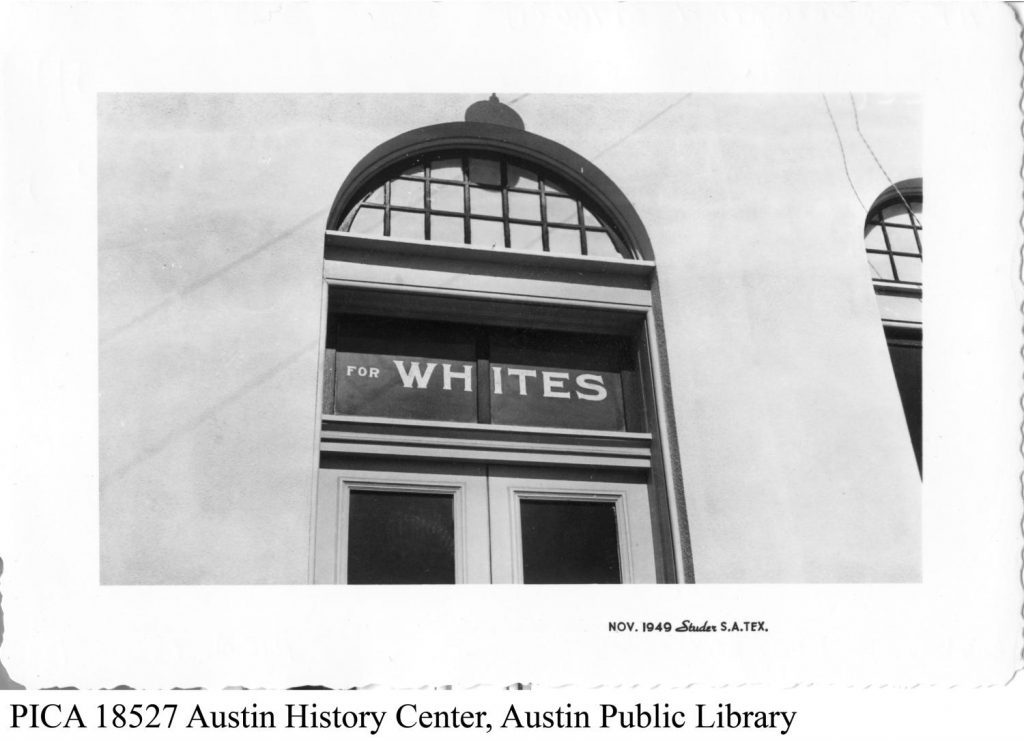

At the same time the contours of the city’s economic character were being reshaped, notions of social justice were largely frozen in the era of Jim Crow of which Austin was still very much a part. Throughout the Civil Rights and Chicano movements, the city’s formal institutions largely remained unchanged and ultimately in service to its White business community. Aside from a few notable exceptions, such as the city council’s first woman representative Emma Long, the city’s Progressive Era government continued to apply the same aging solutions to rapidly changing and emerging problems.

While the first iteration of progressivism was really about smooth, depoliticized local civics, it did carry in its train the beginnings of the consciousness we now associate with today’s progressive ethos, the Civil Rights Movement of course but also immigrants’ rights, a modicum of attention to the poor, the expansion in Texas and elsewhere of educational opportunity. But Austin was a latecomer. Even its community college was not founded until 1973, decades after the idea of universal access to higher and continuing education spread through the nation. Before the height of its “weird” culture, the city grew for a small group of Austinites. With the exception of a few councilors along the way, the local government’s perspective on booster policies was to get out of the way, and allow for the cooperative innovation to take place.

The enduring if forgotten legacy of a consultant named Wood

Emblematic of the start of this evolution was the plan put forth by Richardson Wood, a New-York based planner hired by the city’s chamber of commerce in 1948 to consult on economic development. His recommendations would lay the foundation for Austin’s full embodiment of its character, and for the lasting effects of Progressive Era segregation in gentrification.

It was an era of city development characterized by specialization. Around Texas, other cities took varied routes to specialization: petrochemicals in Houston, military in San Antonio, and banking and commerce in Dallas. In City in a Garden: Environmental Transformations and Racial Justice in Twentieth-Century Austin, Texas, author Andrew Busch detailed Wood’s plan that depended on skilled personnel in the knowledge economy. Under the direction of Wood, Austin continued growing into its identity as a small university town and state capital.

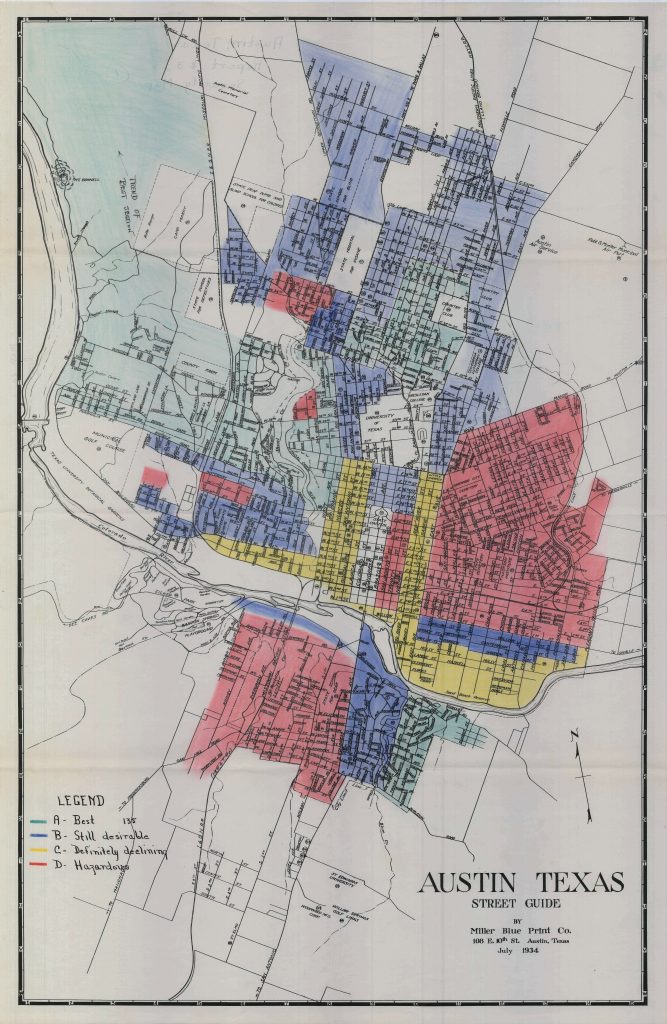

As a proto-“creative class” argument in the language we might use today, Wood suggested the advantage the city should consider was its human resources — and its potential to enhance those resources through development that further hived the city into two distinct realities: A pleasant, well-groomed and White West side and an out of sight, out of mind East side for those who would not be in any promotional brochures. Throughout this time, the city council adhered to Wood’s suggestion to capitalize on its existing comparative and competitive advantages: its people and engineered natural beauty.

“Wood wisely foresaw the university as the primary locus of economic potential, both because of its ability to facilitate business and as a producer of the increasingly sought-after commodity, human capital,” wrote Busch. And Wood was right. Busch connects the need for research and development spurred by the Cold War to the incentives and funding given to universities by federal and state governments around the country. Financial incentives for cities like Austin to increase funding for research in its academic centers united the three levels of government in coordination. Wood’s plan, readily embraced by the city council, fit seamlessly with the goals of Austin’s progressive reform-minded government.

Critics have long argued whether the negative impacts of many Progressive Era policies for racial minorities were intentional. Whether it favored majoritarian policies for the sake of democracy or White supremacy, at-large became notorious for forcibly keeping Black and Latinx people out of political decision-making. Austin may be “weird,” but it is also a southern city with a legacy of racial oppression and segregation. After the 1928 charter enshrined segregation, Interstate 35 locked it in place three decades later, splitting the city in half to create today’s racialized border, with Austinites of color to the East, Whites to the West.

The decades following the enthusiastic reception of Wood’s plan by Austin’s city leaders were marked by civil unrest around the country. As a southern city, Austin was deeply segregated through its laws and norms, organized in its infamous City Plan of 1928. The “race segregation problem” addressed in the plan was unchanged by the Civil Rights Movement, although there were active movements for racial justice and civil rights.

Students from the city’s universities participated in protests against the segregation of lunch counters. African American leaders appealed to government leaders to desegregate public facilities and make the city more equitable for its communities of color.

Separate and unequal even in the Austin of 2020

Largely, as in its government systems, the city followed national trends and desegregation court decisions. In 1954, the year of the first of the landmark Supreme Court decisions in Brown vs. Board of Education, the local NAACP chapter created a petition for the immediate abolition of segregation in public schools. Then, in 1955, the University of Texas Board of Regents voted unanimously to admit African American undergraduate students, and the Austin School Board desegregated high schools. The first Black students to integrate the city’s school would enter Stephen F. Austin, William B. Travis, and McCallum High Schools in 1956. These “firsts” were all met with counter-mobilization from Whites who were committed to uphold the myth of White supremacy, and the city wasn’t forced to comply fully until the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Of course, even this wasn’t the end. Protests against integration and busing continued through the 1970s until the policy was ended in 1987, and the city was continuously sued for its very slow “deliberate speed” in desegregating public spaces and schools. As for school desegregation today, schools here continue to be the most segregated in the entire state of Texas.

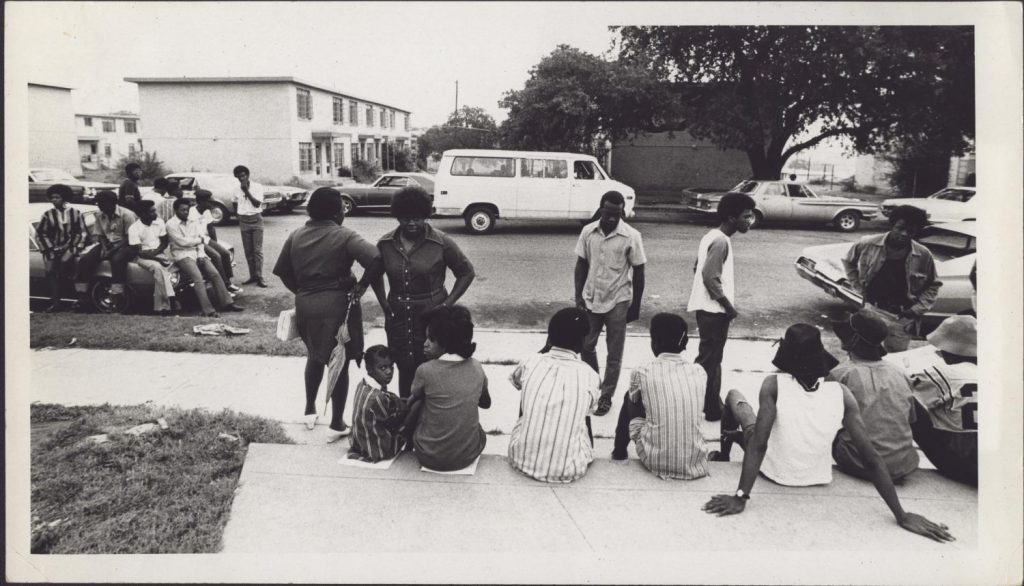

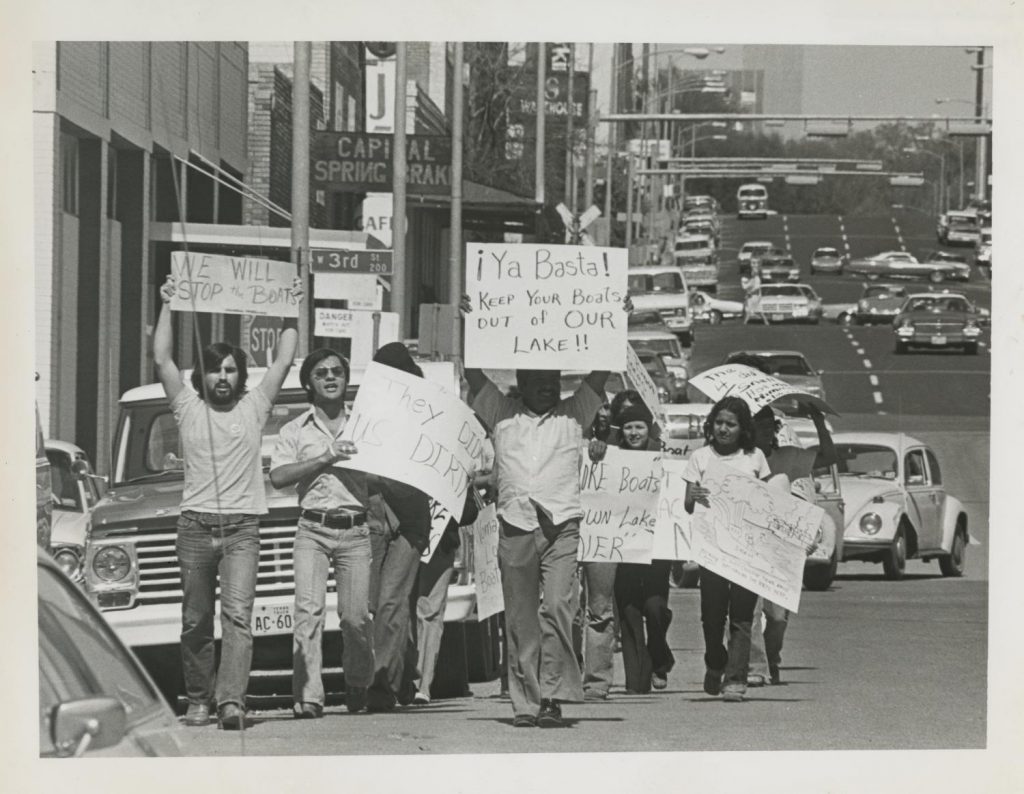

The divisions between Austin’s government and its communities of color were well illustrated in the infamous Aqua Fest boat races, held on the shores of Lady Bird Lake in the early 1960s. The event was popular with the larger population, drawing a crowd of 150,000 at its height in 1968. The Mexican American community, led by the Brown Beret community organization (A Chicano group inspired by Chicago’s Black Panthers), pushed back against the problems brought from the festival. Traffic congestion, noise, and safety concerns were raised by Chicanos, all going unheeded by the organizers and city leaders.

Joseph Martinez, community leader and President of the Guadalupe Community Development Corporation, said of the boat races, “They didn’t care. There was no opportunity East of Interstate 35. It was, ‘whatever we could do to take advantage of and dump on them.’ The high noise levels and so many people coming on to the East side, for what purpose? For money to be made and to be taken out of the community. It was yet another injustice, bad treatment to minorities.”

Poor treatment of communities of color was the consistent downside to the first progressive movement, which Austin continued to embody long after the demise of the movement itself. Events like Aqua Fest were not one-off but cumulative and communities of color demanded among other things, representation on the council. This wasn’t achieved until the 1970s for both the city’s African American and Chicano communities.

The first seeds sown for a true progressivism

Among the seeds of new progressivism in Austin that were planted long before the 21st century, and long before the first councilors of color were elected, were those sown by Emma Long who became the first (White) woman on council. First elected in 1948, her agenda was progressive by the standards of any era and ultimately endeared her to the city, which later renamed City Park as Emma Long Park in 1987. But in her time Long’s pioneering had many Austinites calling her a communist. As councilor, she sponsored policy to revamp the city’s charter and to integrate the golf course and library.

Note that she is referred to as, “Mrs. Stuart Emma Long.” Source: Austin History Center

At the time, Austin politics reflected the rest of the South; a small number of White businessmen led the council, preferring to run the city like a business. City policies at the time were particularly friendly to business interests and strengthened Austin’s reputation as a booster city. Long, however, sponsored ordinances on public administration and civil rights, including an ordinance to prohibit racial discrimination in housing sales. In a city like Austin, with a history full of racist policies such as redlining to deny mortgages to non-White homebuyers, this was a big deal. Long was a true progressive, not only by virtue of breaking the gender barrier. Her tenure represented a push forward in expanding democracy in many ways.

Between the Progressive Era and when the city’s status was cemented as the “weird” oasis deep in the heart of Texas, the seeds were planted. Through the Richardson Woods plan encouraging the city to emphasize its comparative advantage rather than become a military town or petrochemical center, Austin settled into its identity as a university town with the asset of a knowledge economy. And it was from here that the economy would grow into the familiar cluster of technology companies, the “Silicon Hills,” that define much of Austin today.

It would be decades, however, before the city government was reformed to keep up with the city’s more progressive needs.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.