In the 1980s, the United States experienced a new disease that seemed to target young, gay men living in New York City and San Francisco. From the beginning, those doctors and scientists willing to treat members of the gay community remained perplexed as to why these men, their ages ranging from their early twenties to their thirties, were falling ill with rare diseases that would not ordinarily affect someone their age. The earliest name given to this new epidemic was gay related immune deficiency (GRID) before it took the name acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), which was caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The push for scientific advancement and treatment was not readily available to these young men, and many government officials at the state and national levels refused to acknowledge the epidemic that soon spread across the United States and affected groups other than gay men.

In the 1980s, the United States experienced a new disease that seemed to target young, gay men living in New York City and San Francisco. From the beginning, those doctors and scientists willing to treat members of the gay community remained perplexed as to why these men, their ages ranging from their early twenties to their thirties, were falling ill with rare diseases that would not ordinarily affect someone their age. The earliest name given to this new epidemic was gay related immune deficiency (GRID) before it took the name acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), which was caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The push for scientific advancement and treatment was not readily available to these young men, and many government officials at the state and national levels refused to acknowledge the epidemic that soon spread across the United States and affected groups other than gay men.

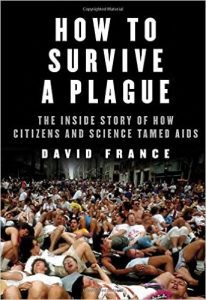

David France’s How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS is a complementary work of history to the 2012 documentary of the same name that documented the early years of the AIDS epidemic to the successful discovery a decade later of combination drug therapies that brought people with AIDS from the brink of death back to life. The main actors in France’s sweeping narrative are a group of men and women who formed the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT-UP, devoted to demanding action from the government and pharmaceutical companies for treatment. Their initiatives were influential in saving thousands of lives by the early 1990s.

ACT-UP began as an informal group of gay men who were dying of opportunistic infections related to the compromised immune systems associated with AIDS. However, as time went on, the epidemic took more lives and the government remained silent, so they took it upon themselves to learn about their illnesses in order to demand government intervention and the development of medical treatments. In this way, many of them became citizen-scientists. They compiled the scientific data made available to them by competing scientists and used it to educate one another and the government officials that they lobbied. They pushed for medications that would treat their opportunistic infections, as well as the virus that causes AIDS once it was discovered. They were also first in realizing the safe sex might lessen the chances a person had for catching this new and mysterious disease.

AIDS activists in the 1980s (Curve Magazine via the Odyssey Online).

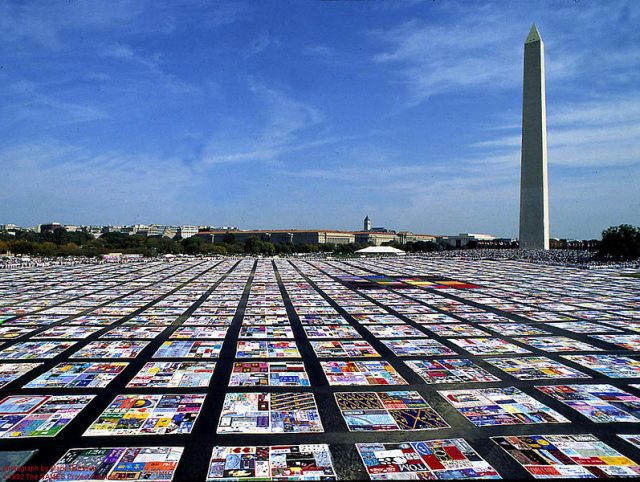

France recounts the activism necessary to win visibility not just for gays, but also for other populations who became affected, such as intravenous drug users and women. ACT-UP’s activism undertook public demonstrations as a means of demanding more scientific research, access to drugs, and lower prices for those drugs once they were identified as possible treatments. In its earliest years of activism, the group modeled itself on the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s by practicing nonviolent civil disobedience and going into traditionally conservative parts of the United States to educate people. ACT-UP petitioned members of Congress for AIDS funding for research, fought with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to allow lifesaving drugs onto the market faster, set up needle exchanges for intravenous drug users, and protested on Wall Street. The early stages of ACT-UP’s activism included using the infamous symbol of the pink triangle with SILENCE = DEATH written beneath it, which was made into bumper stickers and posters that could be plastered all over the city, as well as hats and T-shirts. One of the enduring symbols of their activism is the AIDS Memorial Quilt, which was created in San Francisco to remember the lives lost in the epidemic. It made its first appearance on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1987 when it included more than 1,900 panels.

David France’s book is a great achievement in that he details the events and lives of the people who lived through the AIDS epidemic over the course of approximately thirteen years. France achieves this not simply as a researcher with an eye for historical detail, but also as a person who lived through those events as a journalist. His ability to document the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s resulted in the ability to keenly observe developments while still keeping a certain level of objectivity. France uses extensive archival research, including the papers of the most visible activists and he draws on his own experience. Where possible, France conducted oral interviews with members of ACT-UP who are still alive today. France captures the emotion and frustration of the members of ACT-UP who pushed for access to life saving drugs while negotiating alliances and feuds among members of the group and the scientific community. How to Survive a Plague is essential reading, not only for members of the LGBTQ community, but for everyone who may have been too young or not have been alive during the 1980s and early 1990s when the fight for visibility and medication was still happening. How to Survive a Plague is an excellent example for understanding how activism works, how advocacy for those marginal members of society can be effective, and to show government and public health officials how not to handle a plague.

![]()

You may also like:

Joseph Parrott reviews The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government by David K. Johnson (2006).

Chris Babits explores the Dallas Gay Historic Archives.

Blake Scott reviews AIDS & Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame by Paul Farmer (1992).

![]()