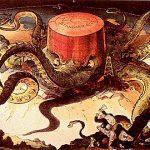

The U.S. Civil War gave new scope to revolutionary currents that ran through the Mississippi River Valley, between St. Louis and New Orleans. This talk focuses on two of the most powerful: African American Conjure and European American Communism. These occult plebeian powers challenged the national ontology of U.S. exceptionalism and the despotism of white supremacy and private property that it entailed. Drawing on Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s 2013 The Undercommons, this talk highlights the intellectual and political work of the self-emancipation enslaved people in the United States.

Andrew Zimmerman is Professor of History and International Affairs in the Columbian College of Arts & Sciences at The George Washington University. He studies revolutions, political thought, imperialism and capitalism. Originally a historian of Germany and Europe, his geographical focus now also includes the United States and West Africa. His teaching and research explore decolonizing approaches to history, including transnational archival research and the use of social and political theory.

His recent research has focused on the global history of the US Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South. He is the author of Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German Empire, and the Globalization of the New South (Princeton, 2010) and the editor of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Civil War in the United States (International Publishers, 2016). He is currently writing a history of the Civil War as an international working-class revolution with roots in Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. It will be called “A Very Dangerous Element.” His first book, Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Chicago, 2001), studied imperialism, science, and popular culture. His scholarship has been supported by organizations including the American Council of Learned Societies, the Guggenheim Foundation, and the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Many of his publications can be found here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.