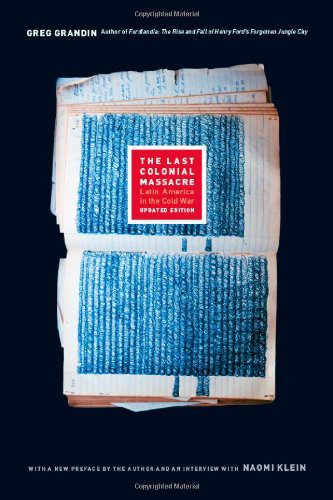

The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War combines incisive analysis of Cold War repression in Guatemala with a history of the country’s century-long mobilization leading up to the 1978 Panzós massacre that resulted in the deaths of Q’eqchi’ Maya men, women, and children. The Panzós massacre launched an intense and brutal escalation of violence, the effects of which continue to reverberate in contemporary Guatemalan society. Grandin’s purpose is manifold. First, he attempts to draw connections between individual identity and political activism. Second, he refutes the North American scholarship that views the Maya as impressionable bystanders caught in the crossfire between the military and the guerrilla. Finally, he historicizes the Cold War, nullifying attempts to naturalize the violence and repression it engendered throughout Latin America.

Alta Verapaz, an important coffee-growing region in northeast Guatemala, has historically been at the center of land disputes between majority Q’eqchi’ Maya and ladino and European settlers. Through the lives of four important figures—José Angel Icó, Alfredo Cucul, Efraín Reyes Maaz, and Adelina Caal—Grandin traces the struggle for land reform there, the end to forced labor, and greater social democratization. Icó, for instance, led a “seditious life” because he rebelled against the authority of the landowning elite by not following traditional paths to male power, though acquiring it nonetheless. He held considerable rural power, stemming from much the same sources as those of the state. Icó wielded his power to weaken a system that reinforced the social and political supremacy of Ladino and foreign elites. Each of these individuals gained new insights concerning their individual roles in the world around them, due in part to their participation in mass politics. Their political development (which was not unique given that many Guatemalans, indigenous and ladino, rural and urban, increasingly mobilized around social causes from at least the 1950s on) dispels analyses that rob Maya of their agency.

Alta Verapaz, an important coffee-growing region in northeast Guatemala, has historically been at the center of land disputes between majority Q’eqchi’ Maya and ladino and European settlers. Through the lives of four important figures—José Angel Icó, Alfredo Cucul, Efraín Reyes Maaz, and Adelina Caal—Grandin traces the struggle for land reform there, the end to forced labor, and greater social democratization. Icó, for instance, led a “seditious life” because he rebelled against the authority of the landowning elite by not following traditional paths to male power, though acquiring it nonetheless. He held considerable rural power, stemming from much the same sources as those of the state. Icó wielded his power to weaken a system that reinforced the social and political supremacy of Ladino and foreign elites. Each of these individuals gained new insights concerning their individual roles in the world around them, due in part to their participation in mass politics. Their political development (which was not unique given that many Guatemalans, indigenous and ladino, rural and urban, increasingly mobilized around social causes from at least the 1950s on) dispels analyses that rob Maya of their agency.

Panzós, a municipality of Alta Verapaz, is the location of what Grandin dubs, “the last colonial massacre.” In 1865, a group of Maya peasants appealed to the local government of Carchá, a few miles away from Panzós, for protection against the landed elite. Their demands were met with violent repression. In 1978, a large group of Q’eqchi’s suffered a similar end when they attempted to present their demands to local administrators. Both of these events seem to be by-the-book peasant revolts, but there is something unique about what happened in 1978. This twentieth-century massacre marked the beginning of a new type of counterinsurgent violence that soon spread to other Latin American nations. In tracing the intentionality and premeditation behind Cold War counterinsurgency tactics that transformed the protective power of the state into one that suppressed an internal enemy, Grandin convincingly exposes the “Cold War’s most important legacy”: the destruction of democracy.

Perhaps the greatest contribution of this book is its presentation of a history of individuals neither privileged in life nor in the historical record who have had a lasting effect on other politically active Guatemalans. We know from the outset that Grandin seeks to understand how Q’eqchi’ Maya reformers developed a political consciousness, an identity. This is, among many things, an exploration of how people mold ideology to fit their particular world, their struggle, and what they believe to be their role as engaged citizens.

The wealth of primary and secondary source material used is truly impressive and is another significant contribution of this work to the historiography of repression and state violence in Latin America. Notably, Grandin employs truth commission reports as proper historical sources, which does much to counter critiques of the truth commissions and their reports, Critics contend that these fell short of their lofty goals, to recover the history of state violence and to ensure that history never repeats itself. Maybe it is more precise to say that, in the Guatemalan case at least, the purpose of the truth commissions and their reports was not to ensure that “it” would never happen again; rather, that the point was to preclude a post-civil war, post-Cold War “democracy” from forgetting. The Last Colonial Massacre is a testament to many things, not least of which, is the long life and far-reaching impact of this aspect of the Guatemalan peace process.