La Dra. Nathaly Rodríguez Sánchez estudia la historia feminista de género, con un interés específico en la heteronormatividad y las intersecciones entre teoría política e historia. Investigando ese tema en contextos modernos y coloniales, ella se describe como una “migrante entre siglos, buscando entender la construcción de las estructuras de pensamiento en torno a los cuerpos y los deseos modelados sobre el largo y mediano tiempo de la historia.” Formada como politóloga en Colombia, se apasionó con la historia mientras trabajaba con investigadores especializados en la violencia política en su país, una experiencia que además de llevarla a los archivos también le reveló la ausencia de mujeres en la producción de conocimiento y en las narrativas históricas, las cuales parecían ocultar constantemente a las mujeres bajo la idea de lo general, lo común, o lo masivo. Después de recibir su doctorado en historia por El Colegio de México, empezó a trabajar como Académica Investigadora en el Departamento de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla. Su primer libro, De sedientes seres, abordó la historia del homoerotismo masculino en la Ciudad de México entre 1917 y 1952. En la conferencia magistral que dará para cerrar la XVI Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México (Austin, 30 de octubre-2 de noviembre), elucidará las dinámicas de la hegemonía de género y la heteronormatividad en México y en la mirada de la Historia, destacando la capacidad de maniobra de los actores y sus espacios para la resistencia.

La formación que recibió en la facultad de Ciencias Políticas de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia tenía su fuerte en la teoría política, pero como notó la Dra. Rodríguez Sánchez en nuestra entrevista, generalmente las investigaciones politológicas se enfocan en el presente o en las décadas más recientes, y enfatizan las acciones del gobierno. En su caso, al terminar su carrera tuvo la oportunidad de trabajar como asistente de investigación para académicos especializados en el asunto de la violencia política y también en cuestiones teóricas. Fue esta introducción al trabajo archivístico la que le motivó a interesarse “por las fibras, los hilos que constituyen mundos sociales en nuestro presente, que tal vez pueden sorprendernos por su complejidad.” La experiencia de revisar material archivístico del siglo XIX y XX con el lente de la teoría política, le mostró la capacidad que tiene la Historia para ayudarnos a entender los problemas de “nuestro presente. Pues la historia nos pueda ayudar a salvaguardar dignidades, y también animar espíritus, a dar sentido a la finalidad de las actividades educativas, para ver sus dimensiones políticas.” En la Historia descubrió una herramienta para aumentar y profundizar el entendimiento de cuestiones pertinentes del presente, dando profundidad a las estructuras analíticas ya establecidas en la Ciencia Política.

En el curso de sus investigaciones históricas, la Dra. Rodríguez Sánchez empezó a notar una gran ausencia de mujeres en las reconstrucciones históricas de su país. Aparecían en algunas historias de la vida cotidiana, o se representaban como “una masa anónima de víctimas” en la literatura sobre las guerras civiles de Colombia, pero aún “parecían muy pocas, y entonces empiezo a buscarlas, a buscar cómo hacer esa historia.” La minimización de la presencia femenina en la literatura histórica también la interpeló a revisar sus propias experiencias educativas—en su formación como politóloga, solo tuvo una profesora, y la mayoría de las lecturas fueron escritas por hombres. Mientras tomaba conciencia de esta invisibilización de las mujeres en la historia, la teoría política, y la producción del conocimiento, leía más ampliamente en las Ciencias Sociales y las Humanidades, incluyendo a autoras feministas internacionales, y fue en esa búsqueda que encontró la producción académica de El Colegio de México. Allí conectó con investigadores e investigadoras interesados en asuntos similares, y decidió aplicar para el programa doctoral. Esta institución le atrajo no solamente por sus fuerzas académicas, sino también por su influencia en la opinión pública, y su legado histórico como un lugar de refugio para intelectuales exiliados de países autoritarios.

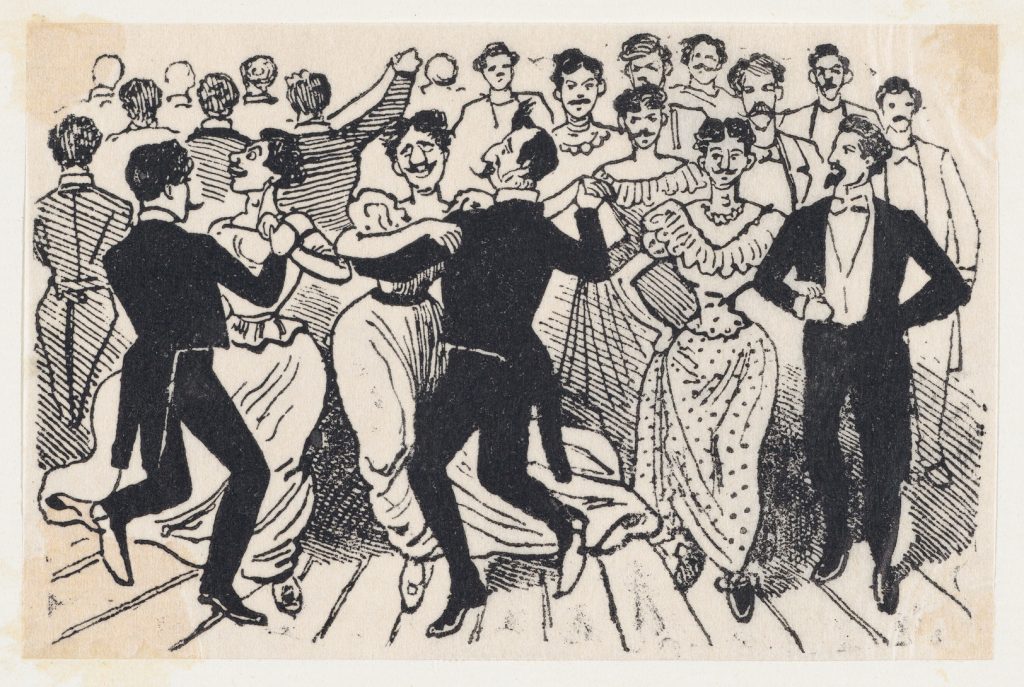

Partiendo de este interés en “recuperar la historia de las mujeres,” en el curso de sus estudios doctorales notó que las historiadoras feministas de género habían enfatizado las experiencias de mujeres, sin investigar demasiado la estructura más amplia de género—por ejemplo, la masculinidad, los homoerotismos o las experiencias de personas no-binarias y transexuales. Además, percibió que la literatura aun cuando entendía el deseo como parte fundamental de esta estructura hegemónica, tendía a analizarlo solamente en torno a las relaciones entre hombres y mujeres. Este acercamiento heteronormativo había borrado la existencia de otras formas de deseo y de amor. La falta de estudios sobre estos aspectos de la historia refuerza un mito—popular entre sectores reaccionarios—según el cual las personas queer no existían en el pasado, o si bien existían, escapan siempre a los historiadores. Ella me explicó que, “quería rescatar las experiencias de muchos que han sido excluidos o permanecen así, y demostrar que existía una tradición falsa que decía que la ‘buena tradición de las familias en México’, del amor de parejas en México, era solamente de la forma heterosexual.” Cuando empezó a trabajar este tema, la mayoría de los estudios históricos ya existentes se concentraban en dos eventos—el Baile de los 41, evento de 1901 que provocó un escándalo y formó parte de una leyenda urbana durante décadas, y el movimiento para la liberación sexogenérica de la década de los 1970. Enfrentando este espacio ambiguo en la literatura, ella se esforzó a entender cómo la comunidad LGBT transita desde el Baile de los 41 en los inicios del siglo XX a la conformación del movimiento en tiempos más recientes.

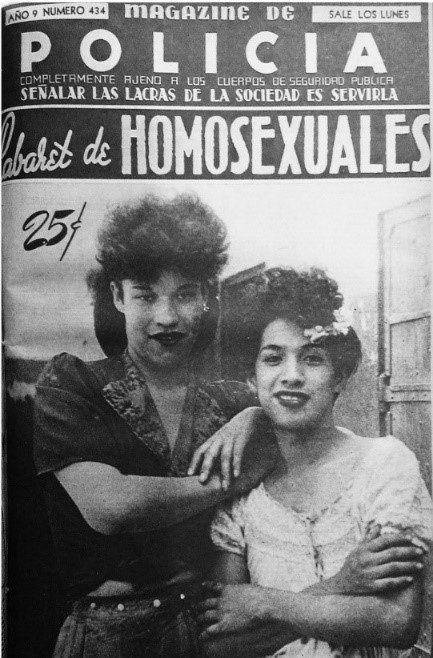

Portada de Magazine de Policía (21 de abril de 1947), año 9, no. 434 (Hemeroteca Nacional de México)/ Cover of Police Magazine (April 21, 1947), year 9, no. 434 (Hemeroteca Nacional de México).

Perderse en los archivos era toparse con muchos mitos y narrativas simplistas. Por ejemplo, muchos historiadores y periodistas habían contado que se encarcelaba a los hombres homosexuales en México, tal y como se hacía en los EEUU o el Reino Unido; pero cuando ella consultó los fondos documentales de las cárceles encontró que la homosexualidad no fue criminalizada de esta manera, por lo menos no en la Ciudad de México. Ella atribuyó este hecho a los impulsos de secularización que se dieron en México a finales del siglo XIX y durante la posrevolución, impulsos que reforzaron una distinción entre los actos inmorales (pensados desde una perspectiva religiosa) y los delitos. Encontró que los hombres con deseos homoeróticos llegaban a la cárcel por otros delitos y no por sus prácticas homoeróticas. En todo caso, las autoridades los separaban de otras poblaciones encarceladas designándolos como “pederastas,” término que, a principios del siglo XX en México, no tenía el significado actual en lo que se refiere a relaciones entre adultos y menores de edad. Ella notó entonces las diversas capas de significados que puede tener un término, y los simbolismos que se van sedimentando en ellos. Dar con esta terminología legal y científica le permitió ir tras otras fuentes históricas—a partir de allí, pudo identificar a personas específicas y localizar los lugares que frecuentaban sus actores históricos, un acercamiento microhistórico informado por el trabajo del Carlo Ginsburg. Este trabajo resultó en su primer libro, De sedientos seres, publicado en 2020, con su título que retoma un verso de un poema homoerótico del escritor mexicano Xavier Villaurrutia.

Mientras terminaba su primer libro, veía que en México era casi nulo el trabajo histórico sobre el homoerotismo femenino. Como ella me explicó, la mitología heteronormativa, que ha oscurecido la presencia del homoerotismo o las identidades de género fuera del binarismo estricto entre mujer y hombre, funciona como “sentido común” para muchas personas hasta el presente. Para llegar a este punto, una idea necesita pasar “por siglos de socialización, por muchas bocas de párrocos, de educadores de infancia que lo han repetido al punto de no ser siquiera pensado como sentido de actuación.” Este hecho la compeló a desviar su mirada hacia el periodo colonial. Utilizando fuentes de la Inquisición y otros archivos de Puebla, ha buscado casos que hacen constar la imposición que tiene lugar en la transmisión de ideologías hispánicas de género y de sexualidades. Su estudio actual se enfoca en comunidades mestizas en Puebla con poblaciones altamente blanqueadas, considerando no solamente las dinámicas de la imposición comentada sino también los “espacios ciegos” y lugares donde se permitía hacer resistencia. Este trabajo entrará en diálogo con otras obras en la historiografía latinoamericana, como Gay Indians in Brazil: Untold Stories of the Colonization of Indigenous Sexualities por Estevão Rafael Fernandes y Barbara Arisi; y Femestizajes: cuerpos y sexualidades racializados de ladinas-mestizas por Yolanda Aguilar. Ella basará su primer discurso al Congreso este octubre en esta investigación, atravesando los conceptos e ideas que había perseguido desde su formación doctoral sobre la hegemonía del género y los elementos disidentes que habían resistido la heteronormatividad desde los tiempos de la Nueva España.

En su trabajo en el Departamento de las Ciencias Sociales en la Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla, la Dra. Rodríguez Sánchez colabora con otros colegas para formar una “ecosistema de formación en los estudios críticos de género.” Este ecosistema promueve acercamientos que no solamente repiten las teorías de género “canónicas”, sino que son aproximaciones “situadas” que puedan profundizar y aumentar el entendimiento del género y la sexualidad como estructuradores de desigualdad social y por ende como ámbitos para seguir pensando la transformación social en nuestros contextos—los del Sur global—. Sin embargo, su labor como historiadora y politóloga nunca ha sido crear conocimiento solamente para especialistas—quiere que su trabajo ayude a enfrentar problemas sociales urgentes, como la violencia contra mujeres o personas LGBTQ+. Consciente de la importancia que tienen los espacios de socialización y pedagogía para la formación de nuevos conceptos sociales, ella ha contribuido a los esfuerzos institucionales para crear espacios seguros para mujeres y personas de la diversidad sexogenérica, abogando al mismo tiempo contra las estructuras institucionalizadas en los planes de estudios y en la producción de conocimientos que fomentan la violencia basada en el género. En esta área, me contó que, “la universidad ha estado con oídos abiertos para entender que los espacios educativos también reproducen violencias con base en el género y que tenemos que cambiar nuestros modelos educativos para fijarnos en ello.” Estos temas tienen una resonancia con las dinámicas actuales en Austin, capital de Texas y lugar del congreso donde va hablar sobre su trabajo, ya que el gobierno estatal ha implementado políticas contra la comunidad LGBTQ+ y contra los derechos de las mujeres a la autodeterminación corporal. Es de esperar que sus ideas y teorizaciones interesen a un público diverso, no limitado solamente a los historiadores de México.

Nathaly

Rodríguez Sánchez dará la conferencia magistral, “Entre

chantajes policiales y capacidad disruptiva: geografía homoerótica masculina en

la Ciudad de México de la posrevolución (1917-1952),” en la XVI Reunión

Internacional de Historiadores de México, Austin. Programa e informes: https://xvireunion.utexas.edu/programa/

Entrevista: Timothy Vilgiate (estudiante de doctorado, UT-Austin)

The Spaces of History: An Interview with Nathaly Rodríguez Sánchez

Dr. Nathaly Rodríguez Sánchez studies feminist gender history, with a specific interest in heteronormativity and the intersections between political theory and history. Researching that topic in modern and colonial contexts, she describes herself as a “migrant between centuries, seeking to understand the construction of thought structures around bodies and desires that have been modeled over the long and medium term of history.” Trained as a political scientist in Colombia, she became passionate about history while working with researchers specializing in political violence in the country of her birth, an experience that besides leading her to the archives also revealed to her the absence of women in knowledge production and in the historical narrative, where women were constantly hidden under the idea of a general, common, or mass history. After receiving her PhD in history from El Colegio de México, she began working as a Research Scholar in the Department of Social Sciences at the Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla. Her first book, De sedientes seres, dealt with the history of male homoeroticism in Mexico City between 1917 and 1952. In the keynote lecture she will give to close the XVI Meeting of International Historians of Mexico (Austin, October 30-November 2), she will elucidate the dynamics of gender hegemony and heteronormativity both in Mexico and in the gaze of History, highlighting the maneuverability of the historical actors and their scope for resistance.

The training she received at the Political Science Faculty of the National University of Colombia had its forte in political theory, but as Dr. Rodríguez Sánchez noted in our interview, generally political science research focuses on the present or on more recent decades, and emphasizes the actions of government. In her case, after finishing her degree she had the opportunity to work as a research assistant for academics specializing in the issue of political violence and also in theoretical issues. It was this introduction to archival work that motivated her to become interested “in the fibers, the threads that constitute social worlds in our present, which can perhaps surprise us by their complexity.” The experience of seeing 19th and 20th century archival material through the lens of political theory showed her the capacity of history to help us understand the problems of “our present. For history can help us to safeguard human dignity, and also to enliven spirits, to give meaning to educational activities, to see their political dimensions.” In History she discovered a tool to increase and deepen the understanding of the issues of the present, giving depth to the analytical structures already established in Political Science.

In the course of her historical research, Dr. Rodríguez Sánchez began to notice a great absence of women in the historical reconstructions of her country. They appeared in some histories of daily life, or were represented as “an anonymous mass of victims” in the literature on Colombia’s civil wars, but still “they seemed very few, and so I begin to look for them, to look for how to write their history.” The minimization of the female presence in the historical literature also challenged her to review her own educational experiences––in her training as a political scientist, she only had one female professor, and most of the readings were written by men. As she became aware of this invisibilization of women in history, political theory, and knowledge production, she read more widely in the Social Sciences and Humanities, including international feminist authors, and it was in that search that she encountered the work of El Colegio de México. There she connected with researchers interested in similar issues, and decided to apply for the doctoral program. This institution attracted her not only for its academic strengths, but also for its influence on public opinion and its historical legacy as a place of refuge for intellectuals exiled from authoritarian countries.

Building on this interest in “recovering women’s history,” in the course of her doctoral studies she noticed that feminist gender historians had emphasized women’s experiences, but without much investigation into the broader structure of gender––for example, masculinity, homoeroticisms, or the experiences of non-binary and transgender people. Moreover, she perceived that the literature, while understanding desire as a fundamental part of this hegemonic structure, tended to analyze it only in terms of male-female relationships. This heteronormative approach had erased the existence of other forms of desire and love. The lack of studies on these aspects of history reinforced a myth––popular among reactionary sectors––that queer people did not exist in the past, or if they did, that they would always escape historians. She explained to me that “I wanted to recover the experiences of many who have been excluded or remain so, and to show that there was a false tradition that said that the ‘good tradition of families in Mexico,’ of love between couples in Mexico, was only found in the heterosexual form.” When she began working on this topic, most of the extant historical studies focused on two events––the Baile de los 41 (“Dance of the 41”), a 1901 event that provoked a scandal and formed part of an urban legend for decades, and the sex-gender liberation movement of the 1970s. Confronting this ambiguous space in the literature, she strove to understand how it was that the LGBT community transitioned from the Dance of the 41 in the early twentieth century to the changing movement of more recent times.

To become immersed in the archives was to encounter many myths and simplistic narratives. For example, many historians and journalists had said that homosexual men were imprisoned in Mexico, just as they were in the US or the UK; but when she consulted prison records she found that homosexuality was not criminalized in this way, at least not in Mexico City. She attributed this fact to the secularization impulses that were felt in Mexico in the late 19th century and during the post-revolution, impulses that reinforced a distinction between immoral acts (as considered from a religious perspective) and crimes. She found that men with homoerotic desires went to jail for other crimes and not for their homoerotic practices. In any case, the authorities separated them from other incarcerated populations by designating them as “pederastas” (pedarasts) a term that, in early twentieth-century Mexico, did not have today’s meaning denoting relationships between adults and minors. She then noted the many layers of meanings that historical terms can have, and the symbolisms that become sedimented in them. Mastering this legal and scientific terminology allowed her to go after other historical sources––from here, she was able to identify specific historical actors and locate the places that they frequented, a microhistorical approach informed by the work of Carlo Ginsburg. This work resulted in her first book, De sedientos seres, published in 2020, its title borrowing a line from a homoerotic poem by Mexican writer Xavier Villaurrutia.

As she was finishing her first book, she saw that in Mexico there was almost no historical work on female homoeroticism. As she explained to me, heteronormative mythology, which has obscured the presence of homoeroticism or gender identities outside the strict binarism between woman and man, functions as “common sense” for many people to this day. To get to this point, an idea needs to pass “through centuries of socialization, through the mouths of many parish priests and childhood educators who have repeated it to the point where it is not even thought of as intentional speech.” This fact compelled her to divert her gaze to the colonial period. Using sources from the Inquisition and other archives in Puebla, she searched for cases that show the imposition occurring through the transmission of Hispanic ideologies of gender and sexuality. Her current study focuses on mestizo communities in Puebla with highly whitened populations, considering not only the dynamics of the imposition discussed above but also the “blind spots” and places where resistance was allowed. This work will dialogue with other works in Latin American historiography, such as Gay Indians in Brazil: Untold Stories of the Colonization of Indigenous Sexualities by Estevão Rafael Fernandes and Barbara Arisi; and Femestizajes: racialized bodies and sexualities of ladina-mestizas by Yolanda Aguilar. She will base her first address to the Congress this October on this research, outlining the concepts and ideas she has pursued since her doctoral training on gender hegemony and the dissident elements that had resisted heteronormativity since the times of New Spain.

In her work in the Department of Social Sciences at the Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla, Dr. Rodriguez Sanchez collaborates with other colleagues to form a “training ecosystem in critical gender studies.” This ecosystem promotes approaches that do not just repeat “canonical” gender theories, but are “situated” approaches designed to deepen and increase the understanding of gender and sexuality as framers of social inequality and thus as arenas for thinking about social transformation in wider contexts––those of the global South. However, her work as a historian and political scientist has never been about creating knowledge only for specialists––she wants her work to help address urgent social problems, such as violence against women or LGBTQ+ people. Aware of the importance of spaces of socialization and pedagogy for the development of new social concepts, she has contributed to institutional efforts to create safe spaces for women and gender-diverse people, while advocating against institutionalized structures in the curriculum and knowledge production that foster gender-based violence. In this area, she told me that, “the university has been listening, in an effort to understand that educational spaces also reproduce gender-based violence and that we have to change our educational models and focus on that.” These themes resonate with current dynamics in Austin, the capital of Texas and site of the conference where she will be speaking about her work, as the state government has implemented policies against the LGBTQ+ community and against women’s rights to bodily self-determination. Hopefully, her ideas and theorizations will interest a diverse audience, not limited only to historians of Mexico.

Nathaly Rodríguez Sánchez will give the keynote lecture, “Entre chantajes policiales y capacidad disruptiva: geografía homoerótica masculina en la Ciudad de México de la posrevolución (1917-1952),” at the XVI International Meeting of Historians of Mexico, Austin. Program and reports: https://xvireunion.utexas.edu/programa/

Interview: Timothy Vilgiate (Ph.D. student, UT-Austin)