From the editors: NEP Faculty Features are a new series at Not Even Past designed to celebrate the achievements of faculty and to showcase their wide-ranging work. They are a companion to NEP Author Spotlights which focus on graduate students. In this, the first in the series, we feature the work of Dr Ashley Farmer, who was recently awarded tenure and promoted to Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. This article highlights Dr Farmer’s groundbreaking scholarship while also showcasing her work on Not Even Past.

Dr. Ashley D. Farmer, is a historian of Black women’s history, intellectual history, and radical politics. She was recently awarded tenure as an Associate Professor in the Departments of History and African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Her book, Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (UNC Press, 2017), is the first comprehensive study of black women’s intellectual production and activism in the Black Power era. She is also the co-editor of New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition (NUP Press, 2018), an anthology that examines four central themes within the black intellectual tradition: black internationalism, religion and spirituality, racial politics and struggles for social justice, and black radicalism.

Dr. Farmer’s scholarship has appeared in numerous venues including The Black Scholar and The Journal of African American History. Her research has also been featured in several popular outlets including Vibe, NPR, and The Chronicle Review, and The Washington Post.

Dr. Farmer has received fellowships from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). The Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University, the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Research on Women and Politics at Iowa State University, and the American Association of University Women (AAUW) have also supported her research. She has also been a leader of the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS) and a regular blogger for Black Perspectives.

Dr. Farmer earned her BA from Spelman College, an MA in History and a PhD in African American Studies from Harvard University. She is also the Co-Editor and Curator of the Black Power Series with Ibram X. Kendi, published with NYU Press.

Books

Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era

In this comprehensive history, Dr. Farmer examines black women’s political, social, and cultural engagement with Black Power ideals and organizations.

Complicating the assumption that race and gender constraints relegated black women to the margins of the movement, Dr. Farmer demonstrates how female activists fought for more inclusive understandings of Black Power and social justice by developing new ideas about black womanhood. This compelling book shows how the new tropes of womanhood that they created–the “Militant Black Domestic,” the “Revolutionary Black Woman,” and the “Third World Woman,” for instance–spurred debate among activists over the centrality of gender to Black Power ideologies, ultimately causing many of the era’s organizations and collectives to adopt a more radical critique of patriarchy.

Making use of a vast and untapped array of black women’s artwork, political cartoons, manifestos, and political essays that they produced as members of groups such as the Black Panther Party and the Congress of African People, Dr. Farmer reveals how black women activists reimagined black womanhood, challenged sexism, and redefined the meaning of race, gender, and identity in American life.

Reviews and Praise for the Book

Farmer challenges the basic assumptions of this period that the main role of women was marginal or custodial within Black Power formations, or that black women simply left Black Power organizations to form their own groups in reaction to intransigent sexism during the era. Instead, Farmer describes black women as engaged in intense ideological struggles to shape the political interventions and priorities of the organizations in which they were involved.

American Historical Review

Remaking Black Power is an indispensable triumph. Painstakingly researched, artfully organized, crisply argued, utterly insightful, Ashley Farmer has remade Black Power scholarship like the black women she chronicles. This book unveils and dissects what has been hidden from the Black Power–era for far too long: the black woman as theorist.

Ibram X. Kendi, National Book Award-winning author, Stamped from the Beginning

“Farmer offers students of twentieth-century U.S. history a marvelous gift: an intellectual genealogy of radical black women’s black power activism, grounded in their political theorizing and cultural production and spanning the post–World War II years through the 1970s.”

The Journal of American History

New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition

From well-known intellectuals such as Frederick Douglass and Nella Larsen to often-obscured thinkers such as Amina Baraka and Bernardo Ruiz Suárez, black theorists across the globe have engaged in sustained efforts to create insurgent and resilient forms of thought. New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition is a collection of twelve essays that explores these and other theorists and their contributions to diverse strains of political, social, and cultural thought.

The book examines four central themes within the black intellectual tradition: black internationalism, religion and spirituality, racial politics and struggles for social justice, and black radicalism. The essays identify the emergence of black thought within multiple communities internationally, analyze how black thinkers shaped and were shaped by the historical moment in which they lived, interrogate the ways in which activists and intellectuals connected their theoretical frameworks across time and space, and assess how these strains of thought bolstered black consciousness and resistance worldwide.

Reviews and Praise for the Book

. . . New Perspectives makes an important contribution to the field of intellectual history. Adding African Americans into the larger narrative, using non-traditional sources, and expanding focus beyond well-known black men pushes readers to expand their ideas about the definition of intellectual history and the place of the black intellectual tradition within it . . . It could be used in either upper-level undergraduate or graduate classes about African American history or intellectual history.

The Journal of African American History

This is a marvelously insightful collection featuring contributions by a diverse array of rising stars in our field. In these pages you will learn not only where Africana Studies is headed, but about Intellectual History more generally.

Gerald Horne, author of The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy and Capitalism in 17th Century North America and the Caribbean

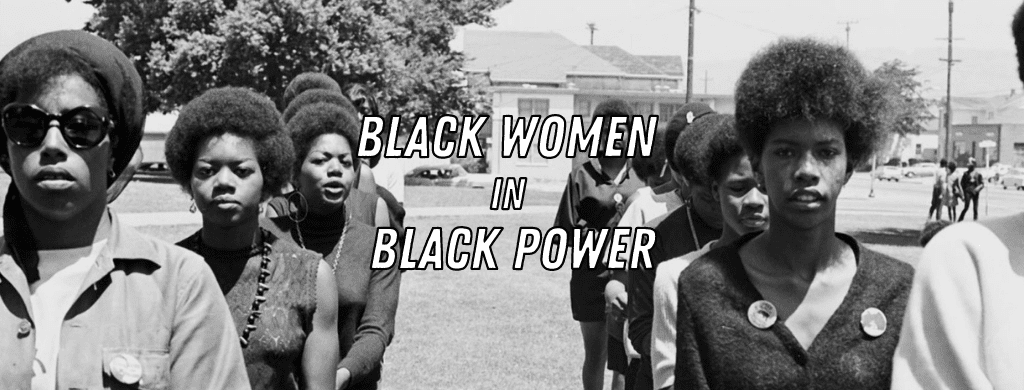

Publications on Not Even Past

One has to only look at a few headlines to see that many view black women organizers as important figures in combating today’s most pressing problems. Articles urging mainstream America to “support black women” or “trust black women” such as the founders of the Black Lives Matter Movement are popular. Publications, such as Time, laud black women’s political leadership—particularly when they mount a challenge to the status quo such as Stacey Abrams’ victory in the Georgia Democratic Governor primary. At the core of these sentiments is the recognition that black women have developed and sustained a liberal democratic politics that is conscious of and responsive to the interconnected effects of racism, capitalism, and sexism and that their approach can offer insight into current socio-political issues. The media often frames these and other women’s efforts as a manifestation of the current political moment divorced from the longer tradition of black women agitators and organizers to which they belong. Many of the black women making headlines today for their work in advancing civil rights and social justice ideals draw from these earlier traditions, including from the Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 70s.

Read the full article here.

Q: This is a large lecture class but you don’t start each class by lecturing. Instead you write that you cede “the floor for the first five minutes of class to a student who wants to raise an issue about campus, Austin, or the national climate.” Can you tell us more about this?

A: I like to always get to the classroom a little bit before class starts. I set everything up and then we just kind of talk informally as a class. I ask what’s going on campus? Or if they saw a certain topic in the news? To give an example around Halloween time, we talked about costumes. I know students are aware of conversations about racism, sexism, and cultural appropriation around costumes, so I will say something along the lines of: did you see this costume I saw online? Does anybody know what’s happening with costumes on UT’s campus? And usually that will allow for someone to speak up about something that they have been thinking about.

I start that way at the beginning of the semester and I find it by mid semester students come in with something they want to talk about. One day, I arrived a bit late, so I didn’t get to do this. And I had one student stop me and say: “What are we talking about today? Because we always talk about stuff before we get started. So what’s our topic today?” They wanted me to go back and do our informal discussion first before we got started with our lesson plan for the day. It made me laugh, but also showed me that they value these conversations that we have together. I think beginning class this way is important for a couple of reasons. Typically, students bring up things that are happening in the world that are related to class. We learned about something, say, the prison industrial complex in class. Students will then bring up an article they have seen about prisons in Texas. Or, we talk about the historical context of policing and then students will want to talk about the school’s relationship to policing or something like that. So these conversations help students connect what’s happening in the classroom to the real world. Also, in the spirit of consciousness raising, it also shows students that I believe that I’m not the only person in the room that can offer valuable information or perspectives or who has something to teach or raise awareness about. We all can contribute to helping each other understand what’s happening on our campus, in the world, around us. And truth be told, because the students live and work and learn on the campus in a way that faculty members don’t, this is honestly where I get a lot of my news about what is happening on campus. So it’s mutually beneficial

Read the full interview here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.