In January 2023, I traveled nearly three hundred miles from my apartment in Buenos Aires to meet a stranger in Paraná, Argentina. We had chatted sporadically via WhatsApp, but I had agreed to spend a long weekend in her home months before we ever met. As I stepped off the bus, I had little sense of what awaited me, yet I was excited to finally meet Luz.

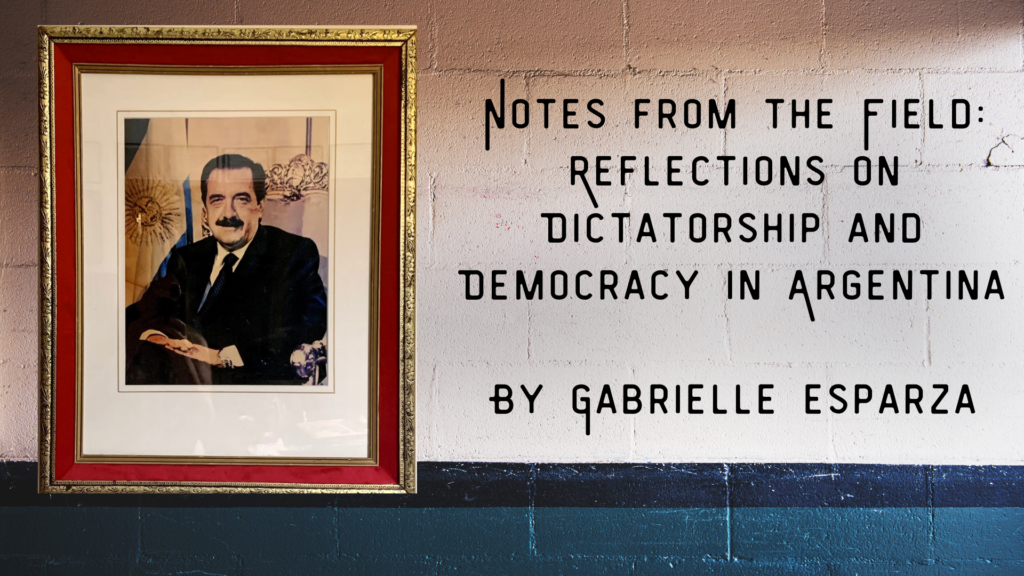

Our meeting happened by chance. A few months earlier, I started research in the Archivo General for my dissertation on President Raúl Alfonsín. He had led Argentina’s 1983 democratic transition, following the country’s longest and most brutal dictatorship. Between 1976 and 1983, the military junta forcibly disappeared an estimated 30,000 people. I had mentioned this project to Álvaro, another doctoral student working in the archives. That weekend he texted me from his friend’s home. “You’ll never believe this,” he said, “but my friend’s parents were friends of Alfonsín.” Accompanying his text was a photo of Luz, walking alongside the president. Álvaro said that he had told Luz about my project, and she had invited me to visit.

Luz’s invitation was unexpected and unusual but also very exciting. I quickly followed up by WhatsApp. She promised to share books and photos from her late husband Enrique’s personal archives. Enrique had held local political office for Alfonsín’s party, la Unión Cívica Radical (the Radical Civic Union, UCR). He had also spent thirty years writing a history of the UCR and its important figures. After Enrique’s death, Luz had undertaken the process of editing and publishing his life’s work. Now she offered to share these materials and her memories of Alfonsín’s presidency with a curious historian from the United States.

Arriving in Paraná in January, I immediately felt overwhelmed. The bus ride from Buenos Aires lasted a little over eight hours, and Luz greeted my tired face with a flurry of questions. I worried that my Spanish would sound rough or that she would regret inviting me. On the way to her home, I tried to organize my thoughts. I had never collected interviews in such an intimate way, and I was anxious not to overstep or offend my host. Luz, on the other hand, seemed eager to begin sharing her stories.

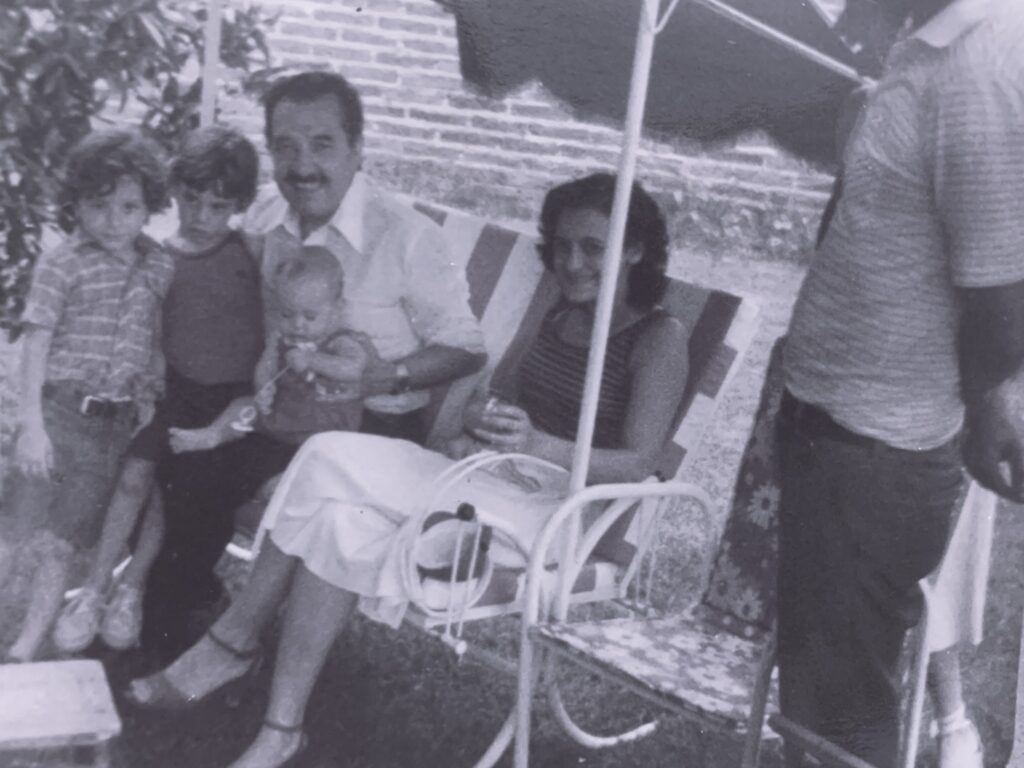

I spent the first full day in Paraná sorting through Enrique’s papers and photos. As I read his work, I gained a better sense of his life and career. Luz helped fill in the gaps—the tiny details that remained outside of her husband’s papers. She remembered difficult years under the military dictatorship. Prior to 1976, Luz and Enrique had participated in local politics and labor unions. The military regime would criminalize these activities, and those who participated risked arrest, torture, or disappearance. Despite the high levels of repression, Luz and Enrique continued to engage in their old social circles and to organize secret political meetings.

A palpable sense of fear permeated Luz’s memories. She spoke of how the couple navigated the constant threat of repression. “We thought one of us should stay . . . stay alive to take care of the children,” Luz said. Often this meant that she stayed home while her husband attended meetings. Other times the couple ignored their fears and opened their own home as a space for political gatherings. They hosted a talk by future president Raúl Alfonsín at their home in 1981—two years before the dictatorship’s end. Luz explained how they had carefully instructed guests to arrive at varying times and in small groups to avoid suspicion. “The only one who wasn’t afraid was Alfonsín,” recalled Luz.

Later, I asked Luz why she agreed to host meetings in her home despite her fears. “I always liked open doors,” she replied. Perhaps that also explained why she willingly invited a stranger to spend the weekend in her home. This openness struck me as remarkable, and our conversations enriched my project. Luz’s recollections might not become the focus of my dissertation, but her stories echo throughout its pages. Often overshadowed in the official narratives, experiences like those of Luz and Enrique are a powerful reminder of the everyday courage and resilience that quietly shaped Argentina’s path toward democracy.

Gabrielle Esparza is a Ph.D. candidate in Latin American history, with a focus on twentieth-century Argentina. Her dissertation revisits President Raúl Alfonsín’s democratic project to examine the intersection of welfare policy and democratization in post-dictatorship Argentina. She holds a B.A. in History and Spanish from Illinois College and received a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship to Argentina in 2017. There she taught at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Gabrielle graduated with her M.A. in History from the University of Texas at Austin in 2020. Her master’s thesis The Politics of Human Rights Prosecutions: Civil Military Relations during the Alfonsín Presidency, 1983-1989 examines the evolution of President Raúl Alfonsín’s human rights policies from his candidacy to his presidency, which followed Argentina’s most repressive dictatorship.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.