You never know. You might be out jogging when your best idea slips into your head. Or one of those random archival documents that you don’t even remember copying turns out to have a key piece of evidence scribbled nearly illegibly along a crumpled margin. Renowned historian Eric Foner just published a book based on a happenstance comment from a student about a rare document she saw in the Columbia University archive.

I was reminded of the accidents of research recently as I was dining at High Table in Trinity College, University of Cambridge. I am fortunate to have a visiting scholarship here this semester to finish a book on the great Russian cinema pioneer, Sergei Eisenstein, and his film about the sixteenth-century tsar, Ivan the Terrible.

And yes, the Trinity dining hall looks just like the one at Hogwarts, with long tables and benches for students running the length of the hall and a more formal High Table along the width. It does, however, have only an ordinary, though impossibly high, ceiling made of wooden beams rather than one that reflects the weather, and while there are plenty of candles, they don’t float in the air. And then there’s Henry VIII. A large copy of Hans Holbein’s famous portrait of Henry, who founded Trinity, watches over diners, as imperious as ever, from above High Table at the end of the hall.

What’s the connection between the accidents of research, a Soviet film about a bloody tyrant of the past –- a film that was commissioned by Joseph Stalin, bloody tyrant of the then-present — and Trinity High Table?

In 1947, when Eisenstein was reflecting back on Ivan the Terrible, which he had recently finished, analyzing the way he tried to convey ideas by triggering all the viewer’s senses, he chose to talk about an unforgettable scene, in which Ivan is mourning his murdered wife, Anastasia, and questioning his own political ambitions. Eisenstein emphasizes Ivan’s doubts and despair by placing him in a dark, shadowy chamber lighted by tall black candles and by using disorienting camera movements and jarring editing. He further conveys Ivan’s inner divisions with sound. From one corner, a priest reads a psalm about isolation, doubt, and loss of faith, while from the other, Ivan’s deputy reads a list of the royal servitors who have abandoned or betrayed the tsar. After listening for a while to this gloomy polyphony and slumping in various anguished positions all around his wife’s casket, Ivan suddenly leaps up. With his energy and determination returning, he reasserts his commitment to seize absolute power and found the modern Russian state: magnificent and ominous at the same time. It’s a powerful scene, where the resolution of Ivan’s inner conflict is made that much more impressive by the wracking pain of the divisions that preceded it.

Writing later about the sensory impact of the scene, Eisenstein suddenly recalled this:

“It was Cambridge.

In 1930.

In Trinity College.

In the huge Tudor dining hall….

On that memorable evening of the late dinner in Cambridge, the voice of the rector [reading a prayer in Latin before the meal] was repeated in response by the voice of the vice-rector.

Candles. Vaults. Two old men’s voices resounding in the boundlessness of the dark hall.

The strange text of the prayer.

The gray heads of the two old men.

The black university gowns. Night all around.

I thought about all this least of all when I was writing the scene of Ivan over the coffin of Anastasia in the screenplay of Ivan.

But now I think this episode of the film is definitely connected with the vivid impressions of that evening long ago in prewar England.”

I had a much more convivial and probably less dramatic dinner than Eisenstein seems to have had.

But you never know.

With thanks to my colleagues, Dominic Lieven and Emma Widdis.

The quoted passage is from Sergei Eisenstein, Nonindifferent Nature. Translated by Herbert Marshall (Cambridge University Press, 1987), p. 311.

You can watch the scene from Ivan the Terrible here: Ivan Grozny (1:19:39)

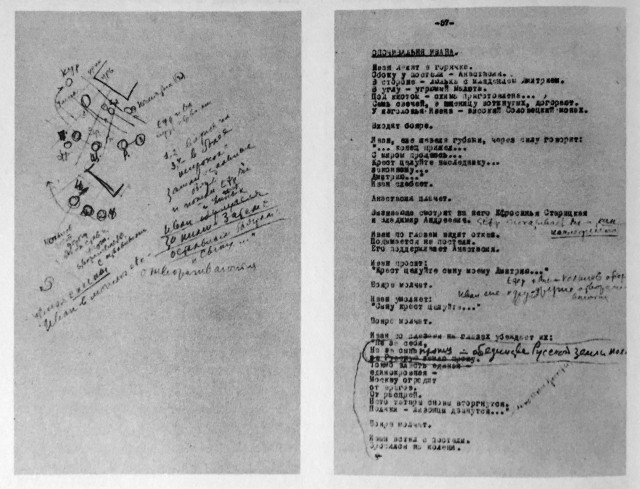

Photo of the script is from Ivan the Terrible: A Screenplay by Sergei M. Eisenstein, transl. Ivor Montagu and Herbert Marshall (New York, 1962), p. 308.