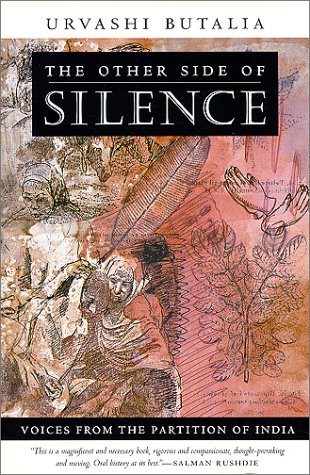

Urvashi Butalia’s remarkable book on India’s partition emerged out of the terrible violence that gripped Delhi, not in 1947, when the partition took place, but in 1984. In the wake of Indira Gandhi’s assassination by her Sikh bodyguard, the citizens of Delhi unleashed a murderous campaign of violence on the Sikh community as a whole. Delhi-ites were horrified to discover both the inaction of the local authorities to provide safety and security for citizens, and the failure of the media to report the atrocities taking place.

In response, South Asian scholars began to see for the first time, the holes in the official narratives of India’s 1947 partition into independent Pakistan and India. In this book, Urvashi Butalia turns to oral histories to tell the real story of the violence in Delhi and across North India in 1947. In Butalia’s oral histories both perpetrators and victims of the violence in Punjab reveal amazing stories of complicity and action. She contextualizes the stories by also narrating an official history of partition that covers the major events, including the story of her own divided family. Linking varied narratives illuminates facets of the partition story that are often obscured by concentration on political histories.

Butalia’s revelation that violence against women during the partition was not always connected to the narrative of religious identity gone awry is an important step in creating a gendered history of partition that shows how women became pawns in a national game about honor and community. The bodies of women came to represent the strength of different communities and their vulnerability exposed the weakness of male protectors.

Throughout these explorations, Butalia’s own concerns about the relationship between nation-building and violence come to the fore. Her oral histories consistently point to violence as an “outsider” act, perpetrated on communities by people from outside those communities. Butalia explains, “as long as violence can be located somewhere outside, a distance away from the boundaries of family and the community, it can be contained. It is for this reason, I feel, that during Partition, and in so much of the recall of Partition, violence is seen as relating only to the ‘other.’”

Many of Butalia’s partition narratives are surprising and touching. They reveal the difficulties of remembering violence and speaking about it aloud. Some of Butalia’s brave narrators remember their own complicity in actions that sharply defined religious difference and marginalized religious minorities, which became one of many reasons the subcontinent was divided.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.