By Nakia Parker

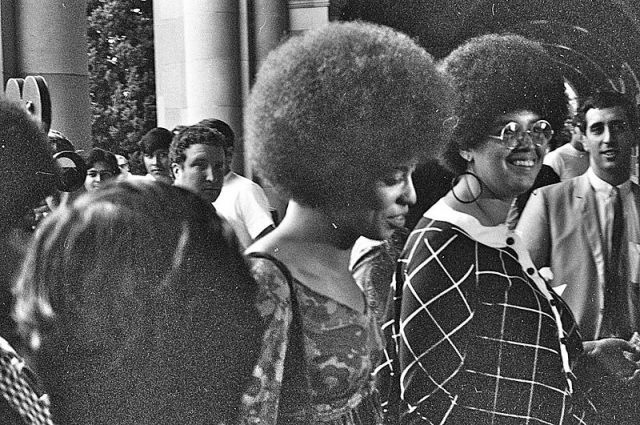

Popular culture can be a powerful tool in helping students understand history. Music, film, TV, fiction, and paintings offer effective and creative ways to bring primary source material into the classroom. Last fall, I gave a lecture on Black Power and popular culture in an introductory course on African American History. We discussed the influence of Black Power ideologies on various forms of popular culture in the 1960s and 1970s. For example, we compared album covers, such as the Temptations’ 1967 album In a Mellow Mood, which has an image of the group in tuxedos and close-cropped haircuts on the cover, singing Broadway standards like “Man of La Mancha,” with another album cover during the Black Power era with the group wearing dashikis, Afros, and singing socially conscious songs, such as “Ball of Confusion” and “Message from a Black Man.” We listened to James Brown’s “Say It Loud! I’m Black and I’m Proud,” and Nina Simone’s “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” and discussed how artists such as Aretha Franklin, who normally did not take a public stand on social issues, would support causes affecting the black community. For example, Franklin posted bail for activist and professor Angela Davis when she was arrested for murder and kidnapping charges. We also talked about how conditions in urban areas and Black Power ideology in the late 1970’s influenced the birth and evolution of rap music and hip-hop culture, from acts such as Run DMC to Tupac to Kendrick Lamar.

The students were engaged and responded well to the lecture. Many of them commented that considering the Black Power Movement through the lens of popular culture changed stereotypes or misconceptions they previously had of the movement and its proponents. When I asked the class before the lecture what words or phrases came to mind when I said the phrase “Black Power,” some students mentioned the iconic image of John Carlos and Tommie Smith during the 1968 Olympics or they associated the movement primarily with violent rhetoric. In addition, many students’ conception of what constitutes primary sources was expanded. Many were pleasantly surprised to find out that songs and film could be used as primary source material. In fact, for the final project, creating a historical time capsule, many of the students used a song as one of their primary document choices.

Film and literature are useful in teaching history as well. In the same guest lecture, I showed the students brief clips of how African-Americans were portrayed in the films Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind, and then compared the two movies’ portrayal of black people as docile and subservient to the scene in the 1975 film Mandingo of the slave Cicero defiantly giving a speech before his execution for leading a slave rebellion. Additional useful films include Saturday Night Fever, which covers more than just disco, addressing topics such as racism, class tensions, religion, and gender dynamics. Apocalypse Now and Born on the Fourth of July encourage students to ponder popular artistic conceptions of the Vietnam War during the 1970s and 80s.

Hattie McDaniel became the first African-American woman to win an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role in Gone With the Wind (via Logo).

For American history before 1865, literature and art can be used as pedagogical tools. When teaching about the formation of “American” identity during the early republic, for example, students might read the short story “Rip Van Winkle” by Washington Irving. Key moments in the story, such as when Rip Van Winkle wakes from his sleep and is confused when he is chased out a tavern and called a spy after he declares his loyalty to the British king, can highlight the upheaval and changes in the new nation after independence as well as the emergence of “American” literature. When discussing the institution of slavery, listening to slave spirituals or work songs can give students a sense of every day life for the enslaved. Finally, when teaching about how Native Americans were portrayed and stereotyped during the late 18th and early 19th centuries before the period of Indian removal, a good painting to analyze would be The Murder of Jane McCrea (1804), by John Vanderlyn, or reading sections of James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans. Both of these sources demonstrate two opposite, but common, views of the time about Indians: as bloodthirsty warriors (Murder of Jane McCrea) or as noble beings, communing with nature (Last of the Mohicans). These images can be supplemented with sources that how Native American life was not static, but adapted to their changing circumstances.

Poster from Last of the Mohicans, a 1920 movie based on James Fenimore Cooper’s novel (via Wikimedia Commons).

As teachers and scholars of the humanities, we constantly need to emphasize the relevance of subjects like history. Using past and present aspects of popular culture as a pedagogical tool is a useful and fun way to remind students why history matters.

![]()

Read more by Nakia Parker on Not Even Past:

Reforming Prisons in Early Twentieth-century Texas

Confederados: The Texans of Brazil

Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South, by Barbara Krauthamer (2013)