“Señor Presidente,” Lyndon Baines Johnson said via a long-distance telephone call from the Oval Office. “We are very sorry over the violence which you have had down there but gratified that you have appealed to the Panamanian people to remain calm.” President Johnson often talked politics on the phone but seldom with foreign leaders. Johnson, who had just succeeded to the presidency of the world’s most powerful country, was speaking to the head of state of one of the smaller nations of the Western Hemisphere. The call marked the only time that Johnson spoke to a Latin American counterpart by telephone during his presidency—a fact that demonstrates how serious he considered the situation. This unique president-to-president phone conversation occurred on January 10, 1964, following the first full day of riots by Panamanian youths along the fence line between Panama City and the U.S. occupied Canal Zone. It was the first foreign crisis of the Johnson presidency. Johnson’s call was translated by a Spanish-speaking U.S. Army colonel, transcribed by the White House staff, and preserved in the archives of the LBJ Presidential Library and Museum.

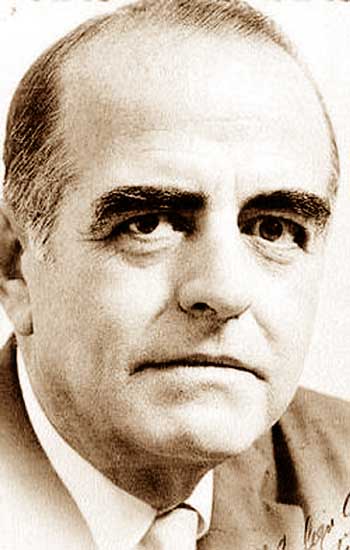

Remarkably, Panamanian President Roberto F. Chiari, more than held his own in this conversation between unequal powers. “Fine, Mr. President,” responded Chiari, “the only way that we can remove the causes of friction is through a prompt and thorough revision of the treaties between our countries.” Johnson answered that he understood Chiari’s concern and said that the United States also had vital interests connected to this matter.

But Chiari did not relent. “This situation has been building up for a long time, Mr. President,” said the Panamanian head of state, “and it can only be solved through a complete review and adjustment of all agreements. . . . I went to Washington in [1962] and discussed this with President Kennedy in the hope that we could resolve the issues,” the Panamanian chief executive explained. “Two years have gone by and practically nothing has been accomplished. I am convinced that the intransigence and even indifference of the U. S. are responsible for what is happening here now.”

Anti-American protests and violence occurred frequently in the decade of the 1960s. Why did President Johnson consider that this riot in Panama amounted to an international crisis that he had to handle personally?

A number of factors explain the importance of Panama to American foreign policy during the early days of the Johnson Administration. He had just assumed office following the assassination of the popular John F. Kennedy, who successfully faced down the Russians in the October 1962 missile crisis. Johnson undoubtedly felt that he also needed to prove his toughness in foreign affairs. His presidential legitimacy was at stake.

Moreover, the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and its challenge to American hegemony in the hemisphere posed a threat that Communism might take over another Latin American nation. No sitting president would win reelection if a “second Cuba” occurred during his watch, and exaggerated reports from Panama were pouring into the White House warning of Communist agents active in the violence. President Johnson already had his eye on the 1964 presidential election coming in just ten months.

Finally, the existence of the U.S.-controlled Canal Zone was becoming a prominent issue in Inter-American relations. The zone itself consisted of ten-by-fifty-mile swath of land surrounding the inter-oceanic canal in which about five thousand English-speaking administrators, operators, and military personnel lived. It divided the Spanish-speaking nations of Mexico and Central America from those of South America. To many, the Panama Canal symbolized U.S. domination over the entire hemisphere.

The Zone also nurtured a colonial mentality among its civilian workers, many of whom had spent most of their adult years there. Surrounded by impoverished Panamanians, the three thousand American citizens operating the Panama Canal tended to be exceptionally patriotic, even jingoistic. Some had never ventured into Panama City. Time magazine once called the Zonians “more American than America.” Many households had Panamanian or West Indian maids and gardeners. Yet the Zonians disdained the Panamanians and refused to fly their national banner. According to canal treaty dating from 1903, the United States occupied the Canal Zone but the Republic of Panama retained sovereignty of the strip of land that split the nation into two parts. Panamanians were demanding that the Americans also raise the flag of Panama too. Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and Kennedy agreed, and each had ordered the joint display of both national banners in the Canal Zone.

However, the Zonians and their school kids disobeyed the presidential mandates. American residents of the Canal Zone, who voted absentee in US elections, enjoyed strong support on Capitol Hill and Senators and Congressmen encouraged their opposition. Congress refused to increase the payments to the government of Panama for the lease of the Canal Zone lands and the Senate stymied the renegotiation of the 1903 treaty.

After six decades of American intransigence, Panamanian students had had enough. On January 9, 1964, they entered the Canal Zone throwing bricks and smashing windows. Arsonists set fire to automobiles and buildings. Fidel Castro’s revolution in Cuba and his anti-American speeches inspired some of the rioters. Others reacted to the nation’s shame about its dependency on foreigners and the presence of the U.S. Armed Forces and the civilian Zonians.

Under these circumstances, American troops stationed in Panama were called out to defend the Canal Zone with small arms fire. During the several days of rioting, twenty-one Panamanians and four American soldiers lost their lives. The wounded numbered in the hundreds. In the final analysis, President Lyndon Johnson’s extraordinary phone call to the Panamanian head of state marked the beginning of a long process of negotiations that ended up, thirteen years later, in the treaty ceding the inter-oceanic canal to control to Panama. President Jimmy Carter and the popular Panamanian dictator General Omar Torrijos signed this agreement at the White House in 1977, and the final stage of the process of transmission came in 1999.

Permit me to add a personal postscript. This research forms part of one chapter of my book manuscript on United States-Latin American relations in the turbulent decade of the 1960s. I myself played a minor role in the drama. During the 1964 Panamanian flag riots, I was an undergraduate student and cadet in the Reserve Officer Training Corps at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Later, as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army, I took up my first foreign assignment at Fort Amador on the Pacific side of the Panama Canal. I arrived in December of 1968, just two months after the coup d’état, by which Lieutenant Coronel Torrijos had seized power. Now I am writing the history through which I have lived.

You can read a full transcript of the conversation here and listen to the audio in the video below (it begins after a brief intro):

[jwplayer mediaid=”4976″]

You may also like:

Mark Atwood Lawrence’s piece about LBJ’s 1964 conversation with George McBundy on Vietnam.

Photo Credits:

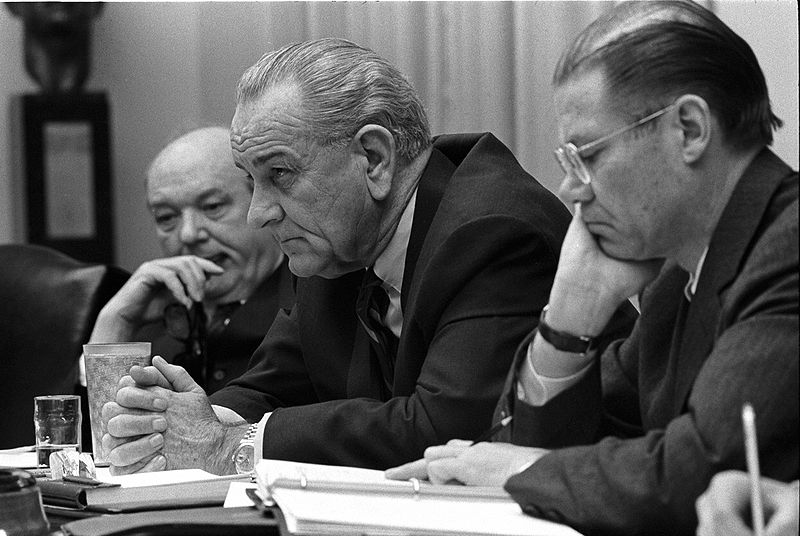

Secretary of State Dean Rusk, President Lyndon B. Johnson, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara at a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House, 1968 (Image courtesy of the United States Federal Government)

Panamanian President Roberto F. Chiari (Image courtesy of La Estrella)

The U.S. battleship Missouri traveling through the Panama Canal, October, 1945 (Image courtesy of the United States Navy)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines