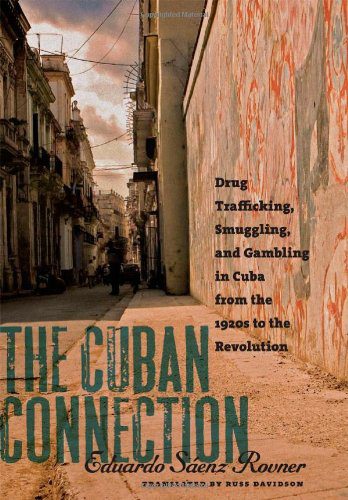

In The Cuban Connection, Eduardo Saénz Rovner rethinks Cuba’s position as a hotbed of drug trafficking, smuggling, and gambling and he considers how these illicit activities shaped Cuban national identity from the early twentieth century through the rise of Fidel Castro. Prior scholarship has largely attributed the growth of narco-trafficking in Cuba to widespread poverty and close proximity to the United States. But Saénz Rovner shows that Cuba’s well-established integration into international migration, commerce, and transportation networks, combined with political instability, judicial impunity, and official corruption, facilitated the consolidation of drug trafficking on the island. He rejects earlier portraits of Cuba as a “victim” of international drug trafficking, arguing instead that native Cubans, as well as immigrants living on the island, played active roles in the development of drug trafficking networks. Finally, he suggests that the “drug problem” fueled the Revolution’s anti-yanquí propaganda machine while simultaneously framing Washington’s efforts to topple the Castro government.

Saénz Rovner examines the influx of Spanish immigration to Cuba and subsequent U.S. capital investment in the island’s sugar industry as catalysts of the social fluidity and economic growth that greatly expanded Cuba’s underground economy in the early twentieth century. Havana, with its cosmopolitan character, dynamic economy, and privileged geographic position, attracted both native and foreign-born drug traffickers who built sophisticated networks that linked Cuba to international chains of supply and demand. The 1940s and 1950s saw the expansion of cocaine and heroin trafficking within a triangle connecting the Andean region, Cuba, and the United States. These illegal drug networks operated in a manner that paralleled Cuba’s trade in legal goods and flourished under the umbrella of an economy tied closely to international commerce and to the infusion of people from abroad. Meanwhile, drugs were not only exported from Cuba, but were also consumed locally. Members of the elite favored cocaine, but their privileged place in society generally afforded them protection from authorities. On the other hand, black and mulatto marijuana smokers and Chinese opium addicts were frequently arrested and prosecuted to the full extent of Cuban law.

Saénz Rovner examines the influx of Spanish immigration to Cuba and subsequent U.S. capital investment in the island’s sugar industry as catalysts of the social fluidity and economic growth that greatly expanded Cuba’s underground economy in the early twentieth century. Havana, with its cosmopolitan character, dynamic economy, and privileged geographic position, attracted both native and foreign-born drug traffickers who built sophisticated networks that linked Cuba to international chains of supply and demand. The 1940s and 1950s saw the expansion of cocaine and heroin trafficking within a triangle connecting the Andean region, Cuba, and the United States. These illegal drug networks operated in a manner that paralleled Cuba’s trade in legal goods and flourished under the umbrella of an economy tied closely to international commerce and to the infusion of people from abroad. Meanwhile, drugs were not only exported from Cuba, but were also consumed locally. Members of the elite favored cocaine, but their privileged place in society generally afforded them protection from authorities. On the other hand, black and mulatto marijuana smokers and Chinese opium addicts were frequently arrested and prosecuted to the full extent of Cuban law.

During the Prohibition era in the United States, Cuba became both a source of contraband alcohol for its northern neighbor and a popular tourist destination for North American tourists who flocked to its mafia-run hotels, casinos, and nightclubs. But mobsters did not introduce gambling, drinking, or even drug consumption to Cuba. Rather, casino construction coincided with Cuban government policies to stimulate tourism and compensate for the fluctuations in sugar prices on the international market. Moreover, Saénz Rovner argues that the expansion of narco-trafficking in Cuba was not the result of mafia entrepreneurship, but was instead a consequence of political instability, a climate of permissiveness, and judicial impunity that hampered the efforts of the Cuban government to suppress the drug trade.

Saénz Rover also considers how drug trafficking advanced political ends during the Cold War. While Henry Anslinger and his Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) falsely accused Fidel Castro of promoting the international drug trade, Cuban revolutionaries accused North Americans of having corrupted the island country by engaging in illicit activities in the pre-revolutionary era.

Eduardo Saénz Rovner challenges studies that tied drug trafficking in Cuba to local poverty and its physical proximity to the United States. Instead, he argues that Cuba’s relative prosperity and success in attracting people and goods from abroad made the island nation an ideal hub for a trans-national drug trafficking industry. He discredits recent works that allege Fulgencio Batista’s personal involvement in the drug trade, exploring how pressure from the United States in fact compelled Batista to pursue large-scale drug dealers. Saénz Rovner shows that drug traffickers took advantage of the worsening security situation in Cuba, slipping away as the Batista regime focused on quelling the civil war and suppressing political opposition. Saénz Rover not only sheds light on drug trafficking in Cuba, but also highlights the multinational character of the “drug problem” by linking illicit industries in Cuba to those in North and South America, Europe, and beyond. But while Saénz Rovner provides a groundbreaking, transnational approach through which to explore narco-trafficking, his study of Cuba is hampered by several historical inaccuracies. In particular, he exaggerates the degree to which post-revolutionary trials and executions discouraged U.S. tourism to Cuba in the wake of the guerrillas’ victory, when in fact tourism had already been on the decline in the twilight of Batista’s rule. Finally, Saénz Rovner frequently mentions the activities of various drug traffickers and Mafioso’s, but does not provide a sufficient historical context so that the reader can understand the significance of these actors to the international drug trade.

Photo Credits:

Old Havana, 2008 (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)

Cuban military dictator Fulgencio Batista and his wife meeting with a US official in Washington, 1938 (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)

You may also like:

Brian Stauffer’s review of Foundations of Despotism, which examines revolution and state formation in the Dominican Republic