by Michelle Reeves

Renowned Russian historian Ilya Gaiduk, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of World History of the Russian Academy of Sciences and author of two monographs on the Soviet role in the Indochina conflict, did not live to see the completion and publication of Divided Together. But he undoubtedly would have been pleased with the result. The book is the first multi-archival English-language exploration of how the politics of the Cold War suffused the functioning and evolution of the United Nations, often to the detriment of the international organization’s fundamental purpose and goals. Though the historical literature on the Cold War is dauntingly vast, not much of it has focused on the United Nations as an arena of superpower conflict.

Renowned Russian historian Ilya Gaiduk, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of World History of the Russian Academy of Sciences and author of two monographs on the Soviet role in the Indochina conflict, did not live to see the completion and publication of Divided Together. But he undoubtedly would have been pleased with the result. The book is the first multi-archival English-language exploration of how the politics of the Cold War suffused the functioning and evolution of the United Nations, often to the detriment of the international organization’s fundamental purpose and goals. Though the historical literature on the Cold War is dauntingly vast, not much of it has focused on the United Nations as an arena of superpower conflict.

Great power disunity in the United Nations often prevented the organization from fulfilling its basic mission. At the heart of the dilemma was the dual nature of the U.N., as both an instrument for negotiating disputes among states and a forum to influence international opinion. Like no other organization that had come before, the United Nations provided a venue for national leaders to appeal to the court of world opinion. Yet the latter function frequently inhibited the efficacy of the former. The use of the U.N. as a Cold War propaganda platform impeded its utility as a mechanism for resolving conflicts. At the same time, however, the United Nations played a key role in de-escalating crisis situations and facilitating their peaceful resolution. The Suez and Cuban missile crises stand out as examples of U.N. efficacy.

Soviet and U.S. views of the U.N.’s utility evolved in response to dramatic changes in the international arena. In the early postwar period, when the creation of the United Nations and the drafting of its charter seemed to many to be dominated by the United States and its Western European allies, the Soviets considered the U.N. to be a mere tool of American foreign policy. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin even went so far as to consider sabotaging the U.N. and replacing it with an organization that would be subordinate to Moscow. The stark bipolarity of the early Cold War period, however, softened in the face of international developments, particularly decolonization, that irrevocably altered the way the Cold War was waged. An influx of members from the newly independent states of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East not only transformed the composition of the U.N., but also sought to influence its agenda. These countries, many of which would later become members of the Non-Aligned Movement, were understandably dissatisfied with the way that the Cold War competition had dominated U.N. proceedings, and sought to redirect the energies of the organization toward easing the transition to independence.

For an academic who was educated while the Soviet Union was still extant, Gaiduk evinces an impressive degree of scholarly professionalism and does not shy away from sharply criticizing Soviet behavior at the U.N. Though the English translation is at times awkward, the content of Gaiduk’s monograph is original, coherent, and persuasive, and successfully bridges the historiography of the United Nations with that of the Cold War.

Photo Credits:

Ambassador Adlai Stevenson displays photos of Soviet missiles to the United Nations, October 1962 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

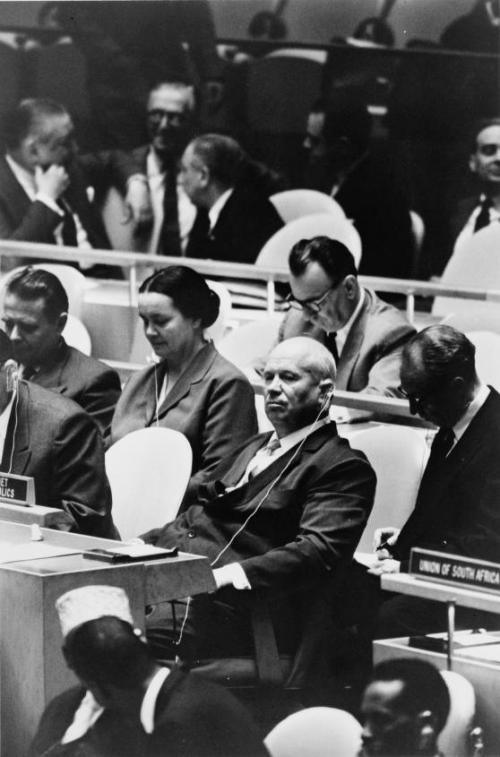

Nikita Khrushchev, leader of the USSR, at a meeting of the UN General Assembly in New York, September 1960 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)