Matthäus Schwarz of Augsburg was, in many respects, a rather typical (if unusually successful) early modern merchant: he worked his way up from an apprentice clerk to a chief accountant in the powerful Fugger banking dynasty, he married, went to war, had children, and, in 1574, he died.  Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

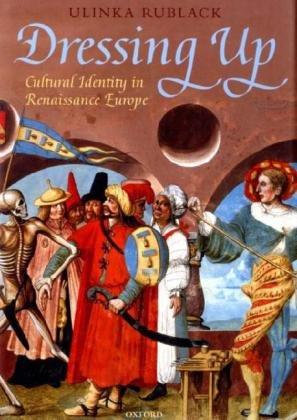

In her brilliant study Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe, Cambridge professor Ulinka Rublack uses Schwarz’s book and other largely unexplored visual evidence to argue that clothes matter in history. In the early modern period, the focus of her study, Rublack sees clothing as comprising a “symbolic toolkit through which people could acquire and communicate attitudes toward life and construct visual realities in relation to others.” Personal adornment could create communities and assert individuality; it could display wealth, express political allegiances, proclaim nationality, and visualize inner emotional states. Indeed, owing to harsh “sumptuary laws” forbidding commoners from wearing luxury goods such as pearls, silks or cloth-of-gold, clothing choices could even be a matter of life or death.

Perhaps the most admirable aspect of Dressing Up is the manner in which Rublack combines sophisticated theoretical arguments about the role of clothing in the “self-fashioning” of Renaissance individuals with concrete, lively details and startlingly vivid illustrations (there are one hundred and fifty six in all, many in color). Rublack has a particularly discerning eye for interesting anecdotes. In the introduction alone, we learn that a gang of youths known as the “Leather Trousers Group” terrorized the streets of 1610s Kyoto, that the French essayist Montaigne hated codpieces, and that medieval contemporaries blamed the defeat of the French knights at the Battle of Crécy on their passion for “clothing so short that it hardly covered their rumps.”

Mathhäus Schwarz’s Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” documented the Augsberg merchant’s personal adornment from infancy to old age. In the image at left, he stands proudly as a youth of nineteen; at right, we see him in the more sombre dress of a middle-aged man.

Jan van Eyck’s 1433 Man in a Turban, a probable self-portrait, forever immortalized a flamboyant fashion choice in the then-new technique of oil paint.

The book’s illustrations range equally widely. Rublack revisits famous self-portraits by Albrecht Dürer and Jan van Eyck to show how Renaissance artists employed their own bodies to exemplify their creative gifts, and uses evidence from a number of well-chosen woodcuts and etchings to demonstrate how clothing choices expressed national and religious allegiances. Particularly interesting — because they are so rarely used as historical evidence — are the photographs of actual clothing from the medieval and early modern periods. Rublack analyzes an incredibly closely-fitted silk doublet once owned by a medieval French duke, for instance, to argue that the rise of tight-fitting male clothes in the fourteenth century “reinvented masculinity and femininity, as well as a sense of what critics regarded as effeminate.”

Dressing Up draws much of its evidence from the German-speaking lands of the sixteenth century, and a notable secondary argument running through the book is that early modern Germany was far more connected to the wider world than has typically been admitted. Banking houses like Matthaüs Schwarz’s employer, the Fuggers, played an especially important role as financiers of long-distance trading voyages, and Rublack’s book shines in its exploration of how German printed texts made sense of the sartorial choices of indigenous groups beyond Europe (Chapter Five, “Looking at Others”). Throughout, Rublack’s clear writing style admirably balances intellectual heft and archival expertise with a spritely and quietly humorous authorial voice.

Like the “Book of Clothing” of Matthaüs Schwarz, this book is much more than a catalogue of obsolete clothing styles. It is an exploration of human nature, and of how human beings throughout history have expressed their inner lives through their exterior coverings.