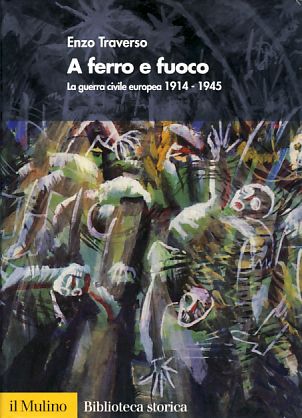

by Alexander Lang

The period from 1914-1945 has sometimes been called a “European Civil War,” but that concept has rarely been put to a systematic examination. Fortunately, Italian historian Enzo Traverso’s recent work A Ferro e Fuoco, which can be loosely translated as Put to the Sword, offers some intriguing proposals for understanding the period as a continental civil war. For Traverso, this larger perspective is important as Europe continues to struggle with the memory of the violence unleashed by two world wars. Only by entering the moral and psychological world of the actors of the time, he claims, can we comprehend the ever increasing systems of violence that culminated in the Holocaust.

One of the focal points of the book is how conceptions of legality changed during the period. Traverso employs the ideas of the German legal scholar (and Nazi supporter) Carl Schmitt to explain how the pre-1914 liberal order fell to the harsh legality of civil war. According to Schmitt, in a civil war, the two opposing sides each represent a different legal order, which requires that each place its enemy in a state of illegality. Before 1914 this ability of a sovereign to declare enemies illegitimate had been reserved to domestic civil wars and to the colonies. But when the Bolshevik Revolution challenged the legal structure of nation-states by representing an idea rather than a political entity, many Europeans sought to not only crack down on domestic supporters of communism, but to help overthrow, and then quarantine, the Bolshevik “virus.”

From the beginning of the Russian Civil War (1918) until the end of the Second World War, both fascists and communists, and sometimes liberal-democrats, denied the legal legitimacy of certain groups and individuals (such as political opponents, immigrants, ethnic minorities, and others) in order to either protect the sovereignty of the state or to provide the state with tools to construct a new legal order based not on the past, but on ideological imperatives. This culminated in Germany’s invasion of Russia in 1941, a war conceived by the Nazis as an existential struggle of annihilation. It is therefore not surprising that the Allies demanded that Germany surrender unconditionally, and later executed Wilhelm Keitel, who had represented the German armed forces at the surrender. Such actions would have been inconceivable in earlier wars between nations, but the European Civil War could only be resolved through the elimination of an opponent deemed illegitimate by the victors.

Traverso suggests that our modern liberal-democratic sensibilities are offended by the ease with which many leftists and rightists turned to the legal exclusion and violent targeting of groups seen as a threat. He fears that the consequent valorization of those who stayed neutral and “above” the fray will lead us to forget how discredited the liberal order was, and how the often violent means of revolutionaries and resistance fighters were the only realistic response to the threat of Nazism and Fascism. Furthermore, Traverso argues that while not all of these leftists were communists, only the strength and conviction of communists could have spearheaded the anti-fascist movement that would grant the opportunity for aimless socialists and liberals to regain their sense of strength.

Russian POWs being marched to a German prison camp, 1941 (Image courtesy of The People’s Republic of Poland)

Traverso’s argument is not only legal, as he describes the evolution of violence during the period, as well as the psychological phenomena of fear and hysteria. Within each he shows how the catastrophe of World War I and its aftermath laid the foundations for the greater tragedy that would follow, though he does not go so far as to say that the Second World War was a necessary conclusion to the first. More work will have to be done to demonstrate the continuum of violence and instability linked to the fear and competing legitimacies unleashed in 1914. With that said, Traverso’s work pushes us to place local violence in the broader context of an international struggle, and to place the critical moments of that struggle (the Russian Civil War, the Spanish Civil War, World War II and all of its small civil wars) in a single period marked by constant structural and psychological crisis.

A destroyed farmhouse in Belarus or Ukraine after the German invasion of 1941 (Image courtesy of The People’s Republic of Poland)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines