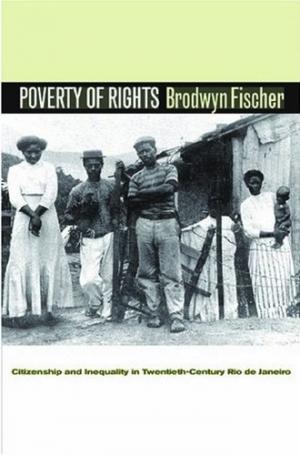

Brodwyn Fischer’s A Poverty of Rights: Citizenship and Inequality in Twentieth-Century Rio de Janiero explores the heterogeneous class of the urban poor in Brazil’s national capital from 1920 to 1950. At the center of the book are the favelas, Rio’s infamous shantytowns, where the majority of the urban poor resided. Although the favelados engaged the legal and political system to win property rights for their makeshift neighborhoods, they failed to achieve full civil rights, which compounded the problems they faced as impoverished city dwellers. Using a wide array of sources such as criminal court cases, oral histories, samba lyrics, newspapers, legal codes, and the correspondence of presidents, prefects, bureaucrats, and governors, the book presents several paradoxes and contradictions. Most twentieth-century Brazilian laws were written in a universal language, yet the urban (and rural) poor were excluded from full citizenship. Marginalized, Rio’s poor still played a crucial role in city politics. City ordinances outlawed favela settlements, but the residents of the shantytowns, in many cases, gained recognition of their neighborhoods and remained anchored to Rio’s hillsides. Informality, however, became critical to the poor’s pursuit of rights. Civil rights in twentieth-century Rio de Janeiro became privileges of social and economic class, not universal entitlements.

From the beginning, the capital’s poor residences were left out of the city’s planned development. Sanitation campaigns in the early 1900s pushed the destitute to the city’s fringes – the hillside and suburbs.

The Rocinha favela, one of the largest and oldest in Rio.

These neighborhoods were outlawed because of sanitary conditions and building codes, and then received little or no public sanitation, running water, paved roads, electricity, or public transportation. Yet in-migration to Rio in the 1930s and 1940s caused a housing crunch to turn into a housing crisis as the population of the illegal city reached some one million inhabitants. The favelados demanded public services, and politicians at least paid lip service to the causes of Rio’s poorest residents. Illegality, in other words, became a cheap form of political currency.

The culture of the poor and their ideas of work and family differed from those of President Vargas, the so-called “father of the poor,” which further marginalized them. The Vargas regime in the 1940s-50s, extolled workers as vanguards of economic progress and national identity, but rarely dignified occupations such as washerwomen, janitors, and servants. While the regime idealized women as housewives, poor women often worked all day to sustain their families and lived in informal unions with their partners.

Rio’s Vidigal favela viewed at dusk.

Furthermore, the majority of poor workers were excluded from Vargas’s labor legislation because they could not meet the requirements or obtain the numerous official documents necessary to gain labor benefits. The documents were expensive, the bureaucratic red tape was complex and the process slow, and many poor people did not even have birth certificates to begin the whole process.

Documents, in other words, became passports to citizenship. But the kinds of work the poor performed were not even reflected in the worker legislation, which favored industrial labor.

In the courts as well, Brazilians received differential treatment based on social and economic standing. Middle class defendants were more likely to have their cases dismissed, while the poor were more likely to receive guilty verdicts and harsher punishments. Again, the fact that the poor lacked documents to prove their citizenship undermined their judicial identity status.

By honing in on the diverse group of the urban poor and their relation to the state through civil rights, Fischer explains why and how the destitute of Rio de Janeiro remained only partial citizens. The book is a fascinating read for anyone interested in the connections between politics and economics and anyone concerned with democracy in twentieth- and twenty-first-century Brazil.

Further reading:

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.