by Andrew Straw

Within the span of thirty years, Lev Davidovich Bronshtein (Trotsky) went from living as a revolutionary in exile to being one of the world’s most successful revolutionary leaders, only to spend the waning years of his life back in exile and on the run from the regime whose creation defined his life’s work. In Trotsky: The Downfall of a Revolutionary, Stanford Lecturer and Hoover Archives Fellow Bertrand M. Patenaude provides the definitive account of the events leading up to Trotsky’s assassination by a Soviet agent in August 1940 at his Mexican residence. Patenaude’s work highlights the paranoia, contradictions, ideological stubbornness, cultural intrigues, and violence that led to Trotsky’s eventual exile from the Soviet Union and his tense journey through European exile to Mexico, where Trotsky’s violent past caught up with him.

Few authors bring their extensive archival research to life in the way Patenaude does as he ushers the reader through the last years of Trotsky’s life as if writing a fictional thriller. While thoroughly examining the chronology of events during Trotsky’s exile, Patenaude takes strategic pauses in order reflect on Trotsky’s revolutionary career and give events both global and regional historical context. The author reminds readers how Trotsky lost the power struggle to Stalin, delves into family and sexual matters, addresses arguments made by earlier biographers and examines Trotsky’s influence among Communists and Socialists in the Americas and Europe.

Few authors bring their extensive archival research to life in the way Patenaude does as he ushers the reader through the last years of Trotsky’s life as if writing a fictional thriller. While thoroughly examining the chronology of events during Trotsky’s exile, Patenaude takes strategic pauses in order reflect on Trotsky’s revolutionary career and give events both global and regional historical context. The author reminds readers how Trotsky lost the power struggle to Stalin, delves into family and sexual matters, addresses arguments made by earlier biographers and examines Trotsky’s influence among Communists and Socialists in the Americas and Europe.

Patenaude explores the tensions that Trotsky’s arrival in Mexico created for that country’s leftists and shows how much of his support in the later years came from American Trotskyites from New York to Minneapolis. His friendships with world-renowned artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera mix into the narrative alongside Trotsky’s rivalries with Soviet political contemporaries Stalin, Bukharin, and Kamenev. His relationship with wife Natalia and the sad story of his family both in and out of the Soviet Union is another constant thread. Some of the most intriguing parts of the book examine the assassins and GPU (Soviet secret police) infiltrators whose work eventually led, after one failed attempted, to Trotsky’s mortal wounds.

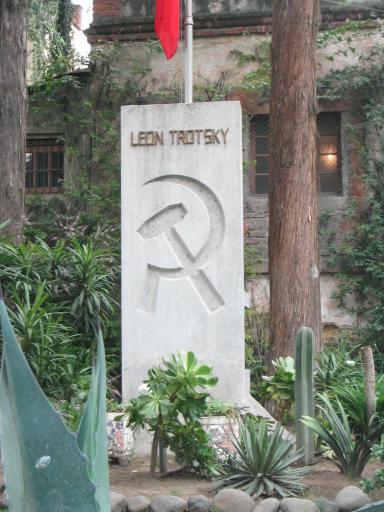

Pantenuade uses his story-telling skills to highlight both the contradictions of Trotsky’s ideological arrogance and portray his real human concerns and sensitivities. Trotsky was an ideologue so stubborn that he could barely agree with many Trotskyites, but he was also talented at seducing women and had a profound love for cactuses. The way in which Trotsky and those around him became increasingly paranoid leads up to the shock and horror of the assassination as it unfolded. One can easily picture oneself standing in the guard’s place and contemplating what steps might have been taken to prevent the inevitable.

Still, the humanization of Trotsky does not necessarily force the reader to sympathize with “the Old Man.” In fact, readers may even be agitated by how such an intelligent and human character could be so stubborn and un-recanting. After all, how could a man who pointed out the dangers in Lenin’s program of centralized terror before 1917 never once question the original Bolshevik revolution, even as the same ideas he once feared were actively hunting him down? Patenaude’s work gives the reader an enhanced understanding of Trotsky’s life and the relevant characters and events leading up to that paradoxical, and bloody fate.

More on Lev Trotsky:

Rare, high quality photographs of Trotsky in Mexico from the Hoover Archives

Bertrand Patenaude discussing his work on Trotsky’s life in Mexico (video)

Trotsky denouncing Stalin (in English) from Mexico (video)