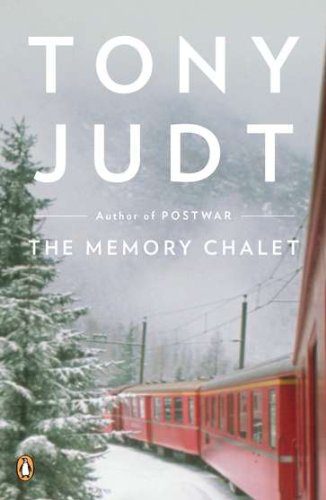

The Memory Chalet stands apart from most memoirs. Written by Tony Judt, renowned British historian, best known for his work Postwar (2005), after becoming quadriplegic as a result of Lou Gehrig’s disease, the memoir began as a memory exercise meant to distract himself from the discomforts of insomnia. While lying in bed, Judt sifted through thoughts and memories until encountering people, events, or narratives he could “employ to divert [his] mind from the body in which it [was] encased.” Soon he discovered that whole stories started to emerge during these nighttime sessions. Unable to write, Judt used the mnemonic device known as the “memory palace” to store these recollections in his mind, though he opted to house them in the quainter, cozier Swiss chalet he remembered from childhood visits to the Alps. Only later did he dictate these stories to an assistant, resulting in the beautifully composed and insightful memoir of an indomitable historian.

The memoir spans Judt’s entire life, combining autobiography with social history. Each chapter focuses on a certain moment from his past, explains its significance, and situates it in the broader history of postwar Europe. For instance, his father’s obsessive compulsion to buy cars reflected the intrinsic nature of his generation (those born in the interwar years) to find solace in the individualism and freedom one experienced in driving on the freeways of postwar Europe, a sentiment Judt’s generation never quite shared. Judt also touches on various other memories from his childhood: living in austerity in postwar England, spending entire Saturdays exploring the London Underground, learning German from a terrifyingly misanthropic teacher everyone in school called Joe. Judt recounts each episode with remarkable ease and carefully explains the importance of each in his life. For example, Joe’s highly disciplined approach to learning German, however terrifying it might have been, helped Judt discover a method for learning languages, which came in handy when he decided to study Czech in his forties.

Londoners walk by the University College Hospital in 1948, where officials had to defuse an unexploded 2,500 lb. German bomb that originally fell in 1941. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The most interesting moments in his memoir come from Judt’s criticism of beliefs he held throughout his life. In his youth, he enthusiastically supported left-wing Zionism, spending three summers in the 1960s volunteering at an Israeli kibbutz and proselytizing Labour Zionism as an official of its youth movement. At the same time, Judt embraced Marxism and participated in the student-led revolutions of 1968 in London and Paris. However, communal life in the kibbutz strained his need for individualism and his experiences in the aftermath of the Six-Day War furthered his falling out with Zionism. Years later he would recant Marxism as well, stating that the real revolutions were happening in Prague and Warsaw. Both revolutions sought to topple the very ideology that Judt’s generation embraced. Distracted by grandiose theories of history, Judt concluded, they had “missed the boat.”

Piccadilly Circus, London, 1966 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The Memory Chalet offers a glimpse into Tony Judt’s development as an historian and as an exceptional thinker. Reading such a unique memoir will surely leave readers with a new appreciation for a greatly missed historian.

Jacob Troublefield is a fourth year History major. Last year he participated in the Normandy Scholars Program. He is currently working on his History Honors thesis about the Congo Reform Movement in Great Britain between 1895 and 1910. His thesis will focus on the various people who led the movement and their influence on the changing character of the movement.