In Jack Finney’s novel Time and Again, the protagonist Simon Morley is taken to a top-secret government facility where time travel is made possible through self-hypnosis. Simon views what seem to be a series of historically accurate movie sets—complete with live actors performing everyday activities—and through extreme concentration he “travels” to the era depicted in those sets.

I read the novel when I was about ten years old, and subsequently attempted the trick myself, building shoebox dioramas and concentrating on the contents in hopes that it would be a portal to some great adventure.

It didn’t work.

I’ve since found another way to access the past through the The New Yorker magazine’s digital archive. By reading every issue—every article, every advertisement starting with Issue No. 1, Feb. 21, 1925— and blogging about it, I am hoping to gain a better sense of how one slice of America was living and thinking in the interwar years and beyond.

The New Yorker, Issue No. 1, Feb. 21, 1925. Many of magazine’s elements familiar to today’s readers were in place from the beginning, including the magazine’s distinctive typography and its famous cartoons. (The New Yorker Digital Archive)

This approach is similar to one taken by writer Laura Hillenbrand when she wrote a bestseller about the racehorse Seabiscuit. In an excellent essay in the July, 7, 2003 New Yorker, she described how a chronic illness forced her to conduct much of the book’s research from home, and in a recent interview with The New York Times Magazine (Dec. 18, 2014), she further related how the research included buying old newspapers on eBay and reading them in her living room as though she were browsing the daily paper. “I wanted to start to feel like I was living in the ’30s,” she told the magazine. “That elemental sense of daily life seeps into the book in ways too subtle and myriad to count.”

The New Yorker’s digital archive doesn’t provide the same tactile experience as newsprint, but each issue is nevertheless an exact scan of the original, some even bearing a past reader’s penciled notes, dog-eared corners, or the shadow of cellophane tape hastily applied over a tear.

My blog, A New Yorker State of Mind, is by no means a comprehensive survey of The New Yorker, but I hope my selections and observations give readers a sense of what was important to the magazine’s editors and writers. In addition to citing actual articles and illustrations from each magazine, I provide some context through research and images gleaned from various sources.

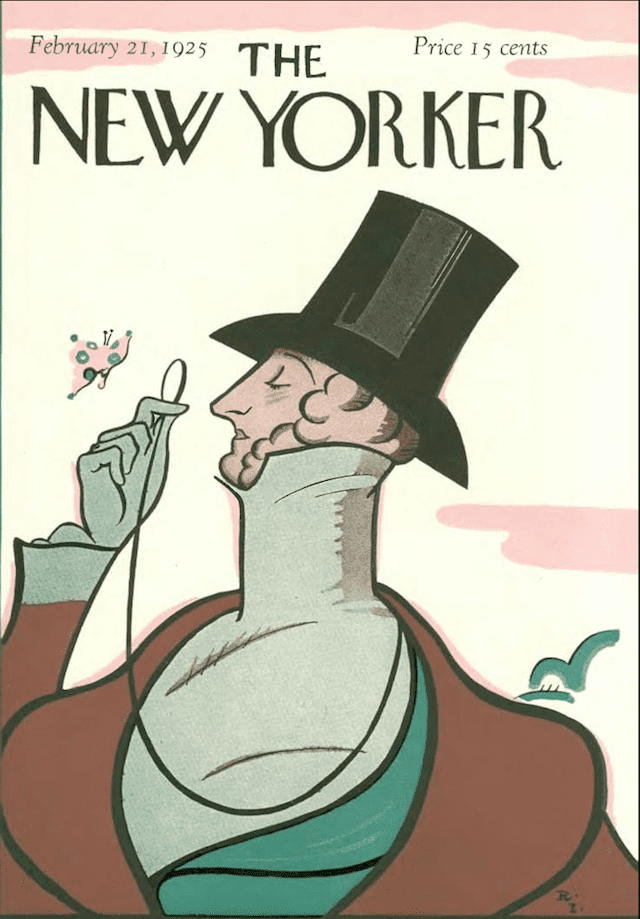

Famously droll cartoons were a New Yorker staple from the very beginning, including this illustration of President and Mrs. Coolidge by Miguel Covarrubias. The president was a frequent target of the magazine for his frugality and bland demeanor. March 14, 1925 (The New Yorker Digital Archive)

The magazine archive not only offers a glimpse into the lives of upper-middle class Gotham strivers, but it is also offers a point of reference to a particular time, and to all of the historic digressions to which it is connected.

For example, the May 2, 1925 issue’s “The Talk of the Town” notes the rapidly changing face of the city—Fifth Avenue mansions are giving way to commercial interests and architectural landmarks, such as architect Stanford White’s Madison Square Garden, are falling to the wrecking ball. In “The Sky-Line” section of the magazine, architecture critic R.W. Sexton noted, in reference to the Garden’s demise, how critics, including foreign visitors, often taunted New Yorkers about their “rabid commercialism.” The following week’s issue (May 9) told of the removal of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ nude “Diana” sculpture from atop the Garden’s tower (which White fashioned after the Giralda of Seville), and an oblique reference was made to Stanford’s White’s scandalous demise, noting that although the manner of the architect’s death put him “in a poor light among his puritanical countrymen,” he was nevertheless courageously defended by the likes of Saint-Gaudens. That sent me back to 1906 (though various scans of tabloids from that time) to briefly revisit how the architect of Madison Square Garden was murdered by the husband of his lover, the actress Evelyn Nesbit, in the rooftop theatre he built in the shadow of his Giralda tower. I returned to 1925 with the understanding that the wrecking ball would be taking away far more than brick and stone.

Photo of Evelyn Nesbit, whose affair with the architect Stanford White led to his death on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden in 1906. Via Wikipedia.

That is what makes this exercise so engaging: one can read the magazine as a contemporary while moving back and forth across the timeline. The blog is also informed by other contemporary readings—newspapers, other magazines, and books such as Patrick Leigh Fermor’s unfinished trilogy recounting his 1933 journey on foot across Europe. Following the Rhine and the Danube on his way to Constantinople, the 19-year-old Fermor occasionally noted in his journal the rumblings of fascism in Germany and Austria, but mostly describing the faded glories of collapsed empires and the many places that retained old ways of life.

However, Fermor did not start writing his trilogy until the 1960s, and didn’t publish the first book in the series, A Time of Gifts, until 1977. It is an account of what a young man hears and sees in 1933, but the omniscient hand of his future self guides his pen. Young Fermor gives us fresh-eyed descriptions of villages and the homely charms of the people, while the older Fermor knows (and occasional notes) that much will be obliterated by the war to come.

So before one gets too carried away, one must be mindful of this “older self” that can haunt a serial reading of The New Yorker. Although I attempt to read the articles and advertisements as though I am living in that time, this is not possible since I possess the foreknowledge of an omniscient reader. When I come across a cheeky account about two buffoons named Hitler and Mussolini, I know a horrible truth awaits my fellow readers.

Foresight and hindsight: A reader of this ad in the May 8, 1937 issue of The New Yorker would be well advised not to book passage on the Hindenburg, because it will not be making the return trip to Germany. (The New Yorker Digital Archive; Wikipedia)

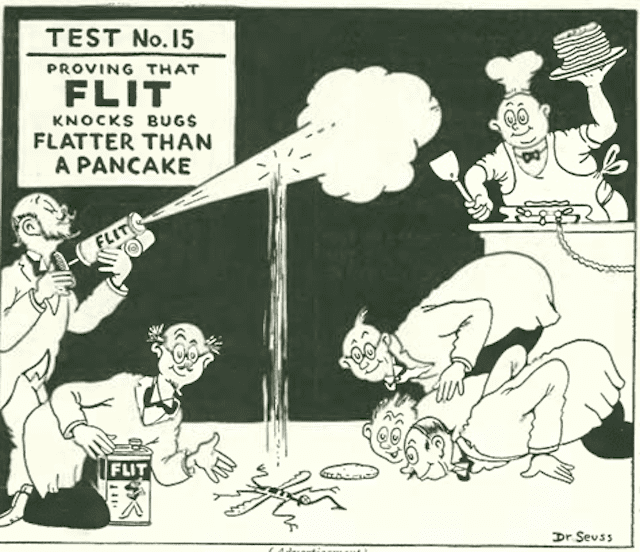

Then there are the advertisements, such as the series that urges indiscriminate spraying of FLIT insecticide (with whimsical drawings by Theodore “Dr. Seuss” Geisel), or the quarter-page ad in the May 8, 1937 issue that invites readers to book a flight on the Hindenburg, which was destroyed on May 6, 1937, claiming 36 lives. The following year Germany would annex Austria, and soon after Czechoslovakia, and the rest is, um, history.

The indiscriminate spraying of FLIT insecticide was encouraged in a series of ads merrily rendered by Dr. Seuss. (The New Yorker Digital Archive)

Which begs the question I often ask myself during my readings: In the midst of the Roaring Twenties, did the New Yorker writers or readers have any idea of what was to come?

The answer so far: No more than we do today.