By Edward Shore

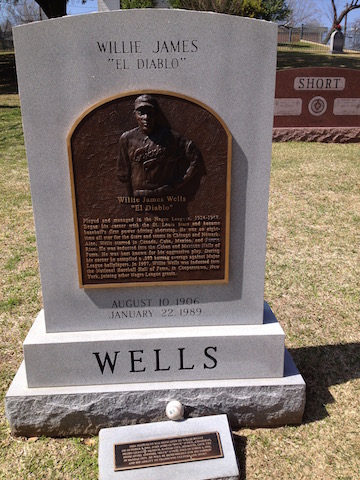

I “discovered” Willie ‘El Diablo’ Wells two years ago on a hot spring afternoon in East Austin. I had decided to skip writing and opted for a stroll down Comal Street, but I was cooked. “Damn it!” I muttered. “It’s too early in the season for this heat!” I took shelter under the pecan trees at the Texas State Cemetery. A bronze headstone caught my eye.

“WILLIE JAMES WELLS, EL DIABLO, 1906-1989. PLAYED AND MANAGED IN THE NEGRO LEAGUES, 1924-1948…BASEBALL’S FIRST POWER-HITTING SHORTSTOP…8-TIME NEGRO LEAGUE ALL-STAR…COMPILED A .392 BATTING AVERAGE AGAINST MAJOR-LEAGUE PITCHING.”

I was enchanted. After all, I’m a massive baseball geek. My morning ritual consists of making coffee, singing along to Mark Morrison’s “Return of the Mack,” and scouring the dark underbelly of the Internet: the fan blogs of my beloved Arizona Diamondbacks. I own a substantial collection of baseball bobblehead dolls. Furthermore, I am an active member of a ten-team Fantasy Baseball Dynasty League. If you don’t know what any of this means, you’re better off for it.

Buried alongside slave owners, the founders of the Texas Republic, and Confederate veterans lay the remains of Willie “El Diablo” Wells, a native Austinite, Negro Leagues standout, and 1997 inductee of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Only I had never heard of Willie Wells before.

“Ignorance is pitiful,” Wells told the Austin American Statesman in 1977. “If you are ignorant and stupid, you are sick- white, black, green, I don’t care.”

I felt ignorant. I felt stupid. I was crushed. Why had Willie Wells fallen through the cracks of my encyclopedic knowledge of baseball?

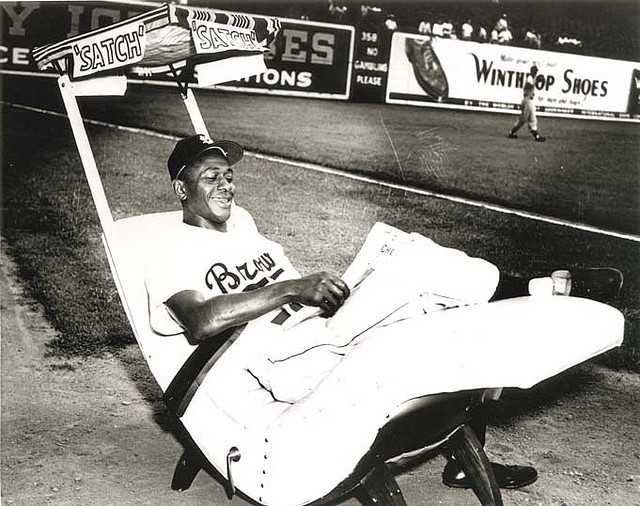

Major League Baseball made black ball players like Willie Wells invisible for over seventy years. A “gentleman’s agreement” among American League and National League owners upheld Jim Crow segregation in the national pastime until 1947. African American stars like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Buck O’Neill earned a living playing for Negro League teams like the Kansas City Monarchs, Homestead Grays, and the Newark Eagles. Between 1923 and 1924, a teenager named Willie Wells starred at shortstop for the Austin Black Senators, a feeder team for Andrew “Rube” Foster’s National Negro League. Wells signed a $300 contract to play for the St. Louis Stars when he turned 18 years old. He chose the Stars over the Chicago American Giants so that his mother could make the day-long train ride from Austin to watch her son play ball in St. Louis.

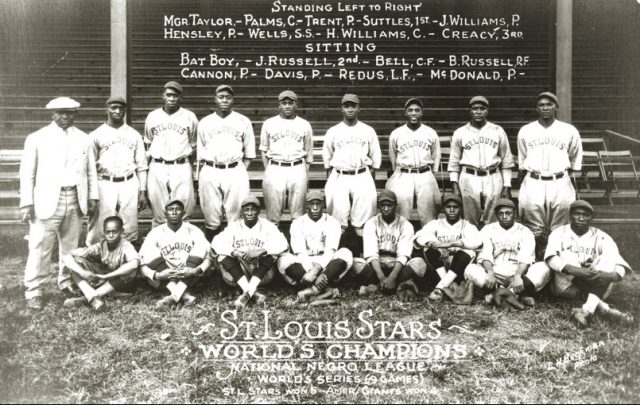

Wells emerged as one of the Negro League’s brightest talents. He and center fielder, James Thomas “Cool Papa” Bell, propelled the St. Louis Stars to the 1928 National Negro League World Championship. The Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) published this photo of the 1928 championship team in celebration of Black History Month. Wells stands third from the right, the only player flashing a smile. His close friend and fellow Hall of Famer, Cool Papa Bell, is seated third from the left.

A terrific base runner and prolific power hitter, Wells honed his craft in the Mexican and Cuban winter leagues, where he earned the nickname “El Diablo” for his ferocious play. He and hundreds of other Negro League players gravitated to Latin America. “One of the main reasons I came back to Mexico is because I’ve found freedom and democracy here, something I never found in the United States,” Wells told the Pittsburgh Courier in 1944. Support for integration grew in the National League in 1946. But Wells was too old to make the jump. Instead, he spent the 1946 season in Montreal coaching Jackie Robinson to master the double-play pivot at second base before his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The story of how Jackie Robinson integrated baseball on April 15, 1947, is well known. MLB has celebrated Jackie Robinson Day since 1997 and all 30 clubs have retired Robinson’s jersey number, “42.” Yet baseball has failed to honor the hundreds of lesser-known African American players like Willie Wells who missed a chance at fame and fortune to segregation. Why? Racism remains embedded in the fabric of our national pastime much like it did in 1887 when Adrian “Cap” Anson, captain of the Chicago White Stockings, refused to play against a Newark, NJ, team with a black pitcher, George Stovey.

Observe the stunning decline of African American major leaguers. In 1986, roughly 20% of the league was African American; in 2015, that number fell to 8%. The unprecedented growth of the NFL partially accounts for baseball’s diminishing popularity. Still, the sport continues to discriminate against people of color in subtle but pernicious ways. Andrew McCutchen, starting center fielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates and the game’s most prominent African American star, recently penned an op-ed that addressed baseball’s failure to attract black youth. He identified the prohibitive costs of year-long youth baseball- equipment, private coaching, tournaments, and travel- as major deterrents for low-income athletes and their families.

Yet the problem runs much deeper. Take, for instance, the exclusionary hiring practices in MLB front offices. Since the “Moneyball revolution” of the late 1990s, many clubs have favored advanced statistical analysis, “sabermetrics,” over traditional scouting to assess player value. Owners have tasked Wall Street executives and Ivy League graduates with backgrounds in finance, management, and statistics with overseeing baseball operations. The result? The rise of a new boy’s club that hires and promotes its own. Owners have flagrantly skirted the “Selig Rule” which requires teams to interview minority candidates for vacancies at general manager and manager. Dave Stewart of the Arizona Diamondbacks remains the lone African American GM in the game. Al Avila of the Detroit Tigers is the only Latino GM. After the Seattle Mariners fired Lloyd McClendon last October, baseball lacked even a single black manager until the Los Angeles Dodgers hired Dave Roberts in December.

Baseball’s discrimination problem doesn’t stop there. The Atlanta Braves will abandon Turner Field in downtown Atlanta for the greener (whiter) pastures of Cobb County in 2017. On the field, players and coaches police a new color line by admonishing African Americans and Afro-Latinos “to play the game the right way.” This vacuous cliché stands as shorthand for “know your place.” In other words, “don’t insult a white pitcher by flipping your bat after launching a majestic home run into the bleachers, or else.” Owners have also taken steps to erase the historical memory of the Negro Leagues. Last year, the Pittsburgh Pirates removed seven statues of Negro Leagues players from “Legacy Square” at PNC Park. One of the casualties was a monument to legendary power-hitter and hometown hero, Josh Gibson. It is no wonder, then, that the story of Austin’s Willie Wells remains unknown to even diehard baseball fans.

Fortunately, the Digital Public Library of America offers an essential introduction to the history of segregation in baseball. Educators can use these and other primary sources in their classrooms to both contextualize and personalize the painful history of Jim Crow. A discussion of the Negro Leagues and race in Major League Baseball in 2016 might also serve as a launching point for students to grasp the pervasiveness of racism in the Unites States. By sharing materials with the public, DPLA will ensure that the tragedy of Willie Wells, Smokey Joe Williams, Monte Irvin and countless others will not easily be forgotten.

To learn more about the Negro Leagues, visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, MO, and the Digital Public Library of America.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.