By Zachary Bradley

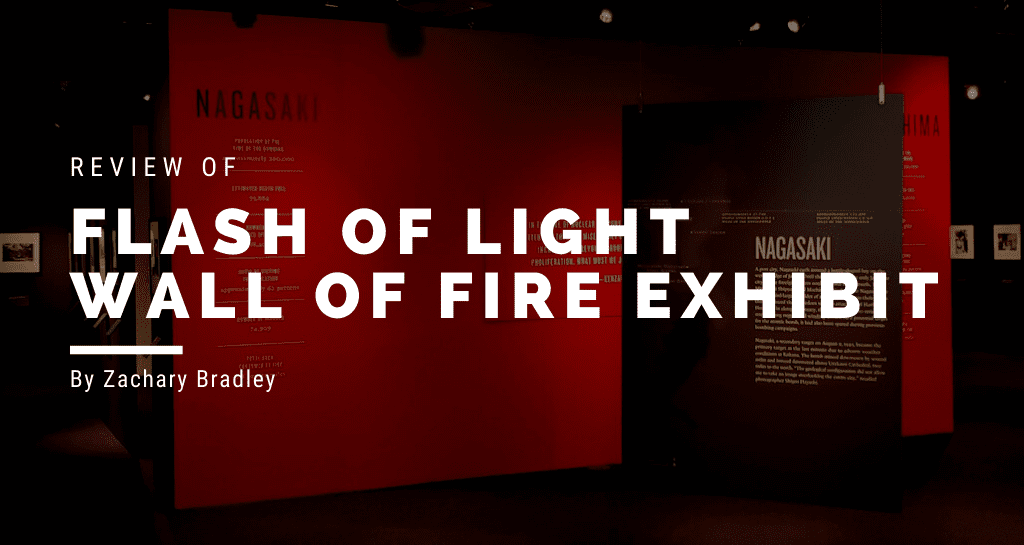

The Flash of Light, Wall of Fire exhibit will be on display at the University of Texas at Austin’s Briscoe Center for American History from August 30, 2021 to January 28, 2022. The exhibit seeks to shows something of the devastation inflicted on the population of Japan by the atomic weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Entering on the right side, the exhibit immediately presents visitors with statistics of the number of households affected, area engulfed in flames, population prior to the bombings, and lives lost. These statistics immediately clarify to the visitor the grave human cost of nuclear warfare.

Between such statistics of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Kenzaburō Ōe, a Japanese writer known for his works dealing with critical political, social, and philosophical issues, in a kind of mission statement for the exhibit, succinctly questions our understanding of nuclear weapons by positing, “In this age of nuclear weapons, when their power gets more attention than the misery they cause, and when human events increasingly revolve around their production and proliferation, what must we Japanese try to remember?”

In line with this statement, the photography of the exhibit does not seek to highlight the bomb, the American decision to use the weapon, or how the bombings have caused nations to hesitate to use nuclear weapons in subsequent conflicts. Equally, the exhibit does not aim to show the weapons itself, but the human suffering caused by humans in their war against other humans and the speed with which we are now able to inflict this suffering.

The photographs of the destruction our sobering. Visitors quickly understand the scale of the destruction through the pictures that display whole city blocks leveled by the shockwave. While this captures the viewer’s attention, even more arresting is the documentation of the suffering of the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Photographs taken from the hospital show the badly burnt citizens of the cities fighting for their lives, shadows of those caught in the initial blast, and rescue forces struggling to respond to the numerous cries for help within their burning city.

The center room, an exhibit of Tsuneo Enari’s photography, offers a unique reflection on the bombing and its consequences. Leaving the world of black and white, Tsuneo Enari’s photography seeks to capture everyday items from the bombing and its victims. Framing the exhibit, a picture of Hiroshima’s Genbaku Dome, the epicenter of the nuclear blast, serves as a reminder of the reality of the destruction. Using pictures of quotidian items such as a dress, melted spectacles, and commuter pass, Tsuneo Enari seeks to capture the humanity of the victims. His work also seeks to explore how victims of the bombing fought for their survival after the bombs dropped. The people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not stop living after the nuclear blast but struggled to find friends, family, loved ones, and new purpose after that day of sudden destruction.

As you exit the center room, visitors once again return to a grim documentation of the bombing. While this return to historical photography might serve to distance the visitors from the lasting consequences of the bombings, the photography serves to solidify the terrible human cost and misery generated by nuclear warfare. As visitors leave the exhibit, a dedication within explains that Flash of Light, Wall of Fire seeks to publicize the work of the Anti-Nuclear Photographer’s Movement. With the ultimate goal of the abolition of nuclear weapons, the organization, founded in 1982, seeks to document, memorialize, and solidify humanity against the use and proliferation of nuclear weapon.

As nuclear weapons far more powerful than those dropped on the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are stockpiled by nations around the world, the essential warning of Flash of Light, Wall of Fire comes at a critical point. While Flash of Light, Wall of Fire is a difficult exhibit to tour as the viewer is forced to confront the immense suffering of the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it serves as an essential reminder and warning against the use of nuclear weapons. A reminder that the destructive power comes with immense human suffering and trauma that even now Japan is seeking to fully understand and overcome.

Zachary Bradley comes from Colorado. He is finishing up as an MA student at the University of Texas at Austin where he has focused his studies on premodern Japan’s response to Dutch expansion. When he is not studying history, he enjoys reading fiction. He particularly enjoys reading works by Kafka and Dostoevsky.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.