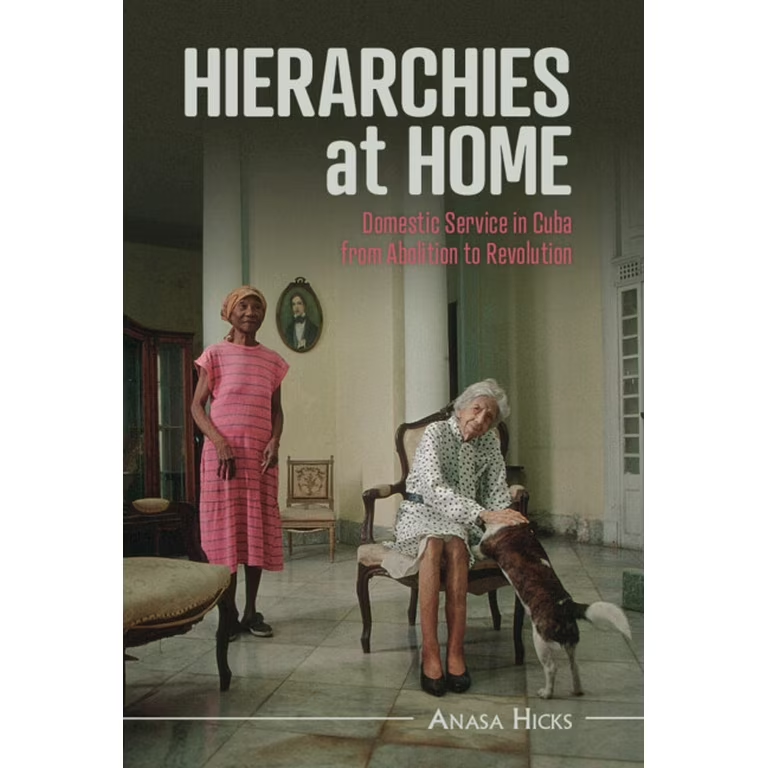

Anasa Hicks has written an engaging and chronologically ambitious study of gender, labor, and race in Cuban history with her book Hierarchies at Home: Domestic Service in Cuba from Abolition to Revolution. Hicks traces the effort to create and deploy the “black doméstica” stereotype—an association of domestic service with African-descended women—throughout late 19th and 20th century Cuba. Investigating the racial anxieties, economic power, and cultural practices of Cubans who employed domestics, as well as the efforts of domestic servants to achieve formal recognition as workers and win legal protections, Hicks illuminates an understudied history of class struggle in Cuba and across the Americas. As she argues, domestics were indeed workers, but the state’s persistent refusal to identify them as such, and the existence of domestic service as an extra-labor category, allowed racialized hierarchies to persist.

By analyzing such diverse sources as manuals on breastfeeding, sexual assault cases, novels, and newspapers articles, the first two chapters of Hicks analyzes the relationship of the domestic worker’s physical body to the Cuban state and the construction of respectable citizenship. Rooted in slavery and the plantation economy, domestic service was work in which African-descended women were over represented. Examining the regulation of prostitution and breastfeeding, as well as cases of sexual assault, Hicks shows how stereotypes about black and immigrant women domestics informed modern legal codes to control and manage their physical, cultural, and moral “hygiene” as Cuba transitioned from colony to republic, from slavery to free labor. Hicks then explores the response from black Cuban “aspiring classes” who rejected imagery of members of their race as only maids, laundresses, chauffeurs, and gardeners. Domestic workers—associated with tropes of servility, sexuality, and poverty—exemplified that which many black Cubans aspiring to the middle class “wanted to escape” (65). In contrast to the Partido Independiente de Color, which addressed structural impediments to black access to wages and education as part of their party platform, the black Cuban middle class promoted “respectable citizenship” predicated on traditional gender roles and family structures.

In chapters 3 and 4 of Hierarchies at Home, Hicks contemplates the struggle between liberal change and radical transformation. Hicks begins examining the 1919 establishment of “domestic economy” schools in Cuba, a government initiative framed as professionalization for women within traditional roles. However, Hicks points out that progressive sectors of the labor movement recognized domestic service as work. Despite the gradual decline of domestic service employment, the visibility of domestic workers as labor activists increased in the 1920s and 1930s, ultimately reaching a “golden age” in the 1940s. Domestic workers defied notions of docility and submission associated with such labor, forming unions and showing solidarity with striking workers in the sugar industry. For example, Elvira Rodríguez, a domestic servant and representative of the Union of Domestic Workers, decried the “fascists of the patio, the reactionaries and the descendants of black slavers” who “try to continue enslaving domestic workers and vigorously distort all that represents liberty, hygiene, organization and culture” (116). The emotional logic of domestic service, however, proved to be a powerful counterforce against domestic workers’ activism, precluding any possibility of their inclusion in the labor reforms achieved throughout the 1930s and in the 1940 constitution. Through an analysis of public reaction to a brief 1938 vacation decree, Hicks effectively illustrates how deeply ingrained social hierarchies and colonial-era racial biases influenced Cuban law, ultimately marginalizing domestic workers and excluding them from formal labor protections, since “formalizing such things as shelter, food, and paid rest would have confused and sullied the naturally intimate relationship between domestics and the families for whom they worked,” conservatives argued (105).

Source: Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b42700

Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-96596 (b&w film copy neg.)

The final two chapters of Hierarchies at Home traverses through the radically transformative events of the 1959 Cuban Revolution to assess how domestic servants fared under the revolutionary process of restoring democracy, protecting workers, and lifting millions out of abject poverty. As the revolutionary government embraced socialism, the need for domestic service was eliminated. In the revolutionary period, memories about domestic service focused on it as a symbol of the deeply racist, sexist, and unequal class society that had been overcome. Hicks, however, laments the declining memory of domestic worker activism pre-1959 in favor of a narrative that privileged the revolutionary transformations post-1959—when domestics in “unprecedented numbers…went to school…becoming doctors, teachers, politicians, and historians” (170). Importantly, Hicks integrates Miami into this study of Cuba, showing how memories about race and gender harkening back to plantation days, or a mythic mid-twentieth century ideal, promoted a vision of the past in which benevolent landholders generously bequeathed gifts to their “inferiors.” Nostalgia also rationalized paying the Black nannies who raised white children with food as an example of family love and affection, not unequal power and authority. Using a fascinating yet unlikely set of sources including interviews with Miami-based Cuban American women for a project about drug usage conducted by researcher Diana González Kirby, Hicks also shows that the loss of access to domestic servants was a regular component of the “economic backslide” experienced by middle-class Cubans who left the island after the revolution. Post-1959, memories about what Cuba was like before the revolution were supposed to bolster anti-Communist arguments, “insisting that race relations before 1959 in Cuba had been fine” (170). This connection between past and present, island and diaspora, offers a valuable perspective on racialized labor and its complex relationship to broader movements for social and gender equality.

Source: Wikimedia commons

Hierarchies at Home provides a nuanced understanding of how deeply ingrained social inequalities can persist in new forms and, at times, be challenged, offering insights for contemporary discussions about labor, race, and social change. For readers interested in social justice and labor history, the book demonstrates how the creation of the “black doméstica” stereotype was not merely a reflection of existing inequalities but an active process that shaped economic power, cultural practices, and even the state’s legal frameworks. By centering the experiences of domestic workers and their struggles for recognition, Hicks unveils a vital, yet often overlooked, dimension of class struggle in Cuba and offers a powerful case study for understanding how race and gender intersect to define who is considered a legitimate worker and citizen across the Americas. While Hicks meticulously examines the experiences of domestic workers and their employers, the book does not primarily delve into the intimate personal relationships and individual motivations within specific households. Therefore, readers seeking a micro-history centered on specific families and their domestic arrangements will find Hierarchies at Home primary contribution lies in its macro-level analysis of the institution of domestic service and its profound implications for understanding the larger forces of race, class, and gender in Cuban history.

Daniel Delgado is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Southern California. His primary research interests include race, labor, migration, and U.S. empire in Latin America and the Caribbean, especially modern Cuba.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.