Most of us prefer to avoid insects. A bee, a cockroach, or a fat yellowish worm confront us with nature’s “ugliness” and present a disconcerting threat to our modern, comfortable being. Perhaps even less appealing than meeting these weirdly shaped creatures is the thought of reading about them. And yet, despite this instinctive response, Edward Melillo’s The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World demonstrates that the same very creatures that we try so hard to avoid are the ones that enabled this comfort to begin with.

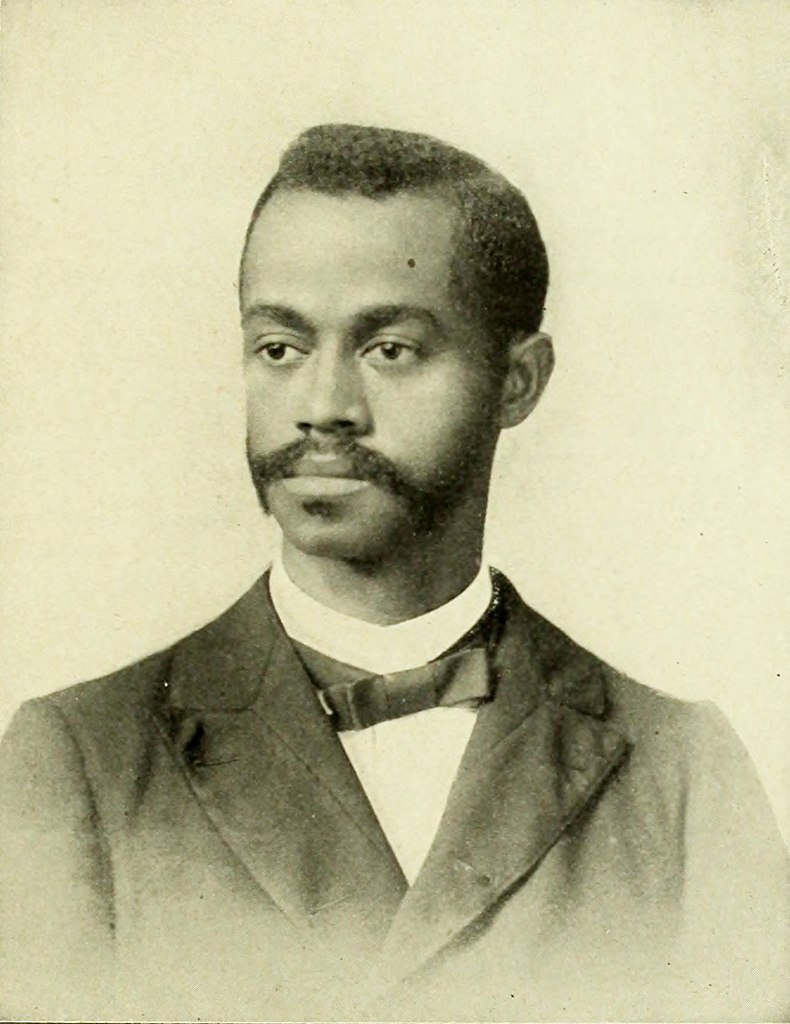

The book accounts for the shared history of people and insects in the last three millennia and is divided into two parts. Part one, made of five chapters, explores the interactions of people with insects through three main perspectives. The first chapter covers some main preconceptions and prejudices about bugs, and how these became a part of contemporary culture. Chapters two to four follow three main insect-related commodities – shellac, silk, and cochineal. These are, in my opinion, the best sections of Melillo’s current project, as they exemplify the capacity of transnational history to help understand the modern world. Chapter five covers the rise of “the synthetic age,” and focuses mainly on the environmental impact of the post-WWII synthetic boom. Part two contains two chapters about the centrality of insects to the scientific discoveries of (to name a few) Thomas Hunt Morgan, Charles Henry Turner, and Karl von Frisch. The final chapter stands as a delicacy of its own and covers the history and future of eating insects.

Melillo’s book is an example of an academic work worth reading for both its substance and style. Students of commodity history, history of science and technology, environmental historians, and curious readers alike will find this work both helpful and inspiring. Through the narrow prism of a bug’s viewpoint, Melillo tackles important questions about the biases of contemporary culture, the inherent contradictions of modernity, tensions between scientific and local knowledge systems, and the future of our decaying plant. Especially impressive are his arguments about the centrality of non-humans to the history of our species. He is careful enough not to call the symbiotic relations between humans and insects coevolution – as our shared history modified neither our nor our six-legged cousins’ genetics. Instead, Melillo proves once and again how the things we take for granted as the result of human ingenuity owe, in reality, a great debt to these creatures.

Melillo’s style appeals to both the academic and the general readership. His previous book – Strangers on Familiar Soil – explored how California and Chile coevolved through mutual displacement, exchange, and influence of people, commodities, and plants since the 18th century. Melillo’s model of shifting back and forth between these two locations inspired scholars to think about cross-regional histories that, until then, remained obscured.

His current book project raises a new challenge – how to write about people and insects, two hyper-globalized creatures that are not bound to a specific location? Melillo’s solution is taken from the rich literature on commodities that might be summarized in one phrase: follow the thing itself. He refuses to bound himself to a specific place and time and takes the readers on a fascinating journey that benefits from an impressive array of historical cases. And so, we get to learn about insects as symbols of beauty in Chinese folklore, their importance to American parachute-making before WWII, and how they are used as social analogies in French literature. Such rich source material and methodological imagination will certainly inspire students and scholars to pursue global and trans-regional history. At the same time, Melillo’s elegant style and clear writing create a smooth narrative from what could have been a dreadful and disorienting collection of various histories. Furthermore, Melillo cleverly avoids convoluted language, historiographical debates, and exhausting footnotes, making the book an accessible read for non-academic curious readers.

“One striking characteristic of commodity history…” Bruce Robbins notes, “is a certain overkill in their subtitles.” And indeed Melillo cleverly never argues that insects were the ones who “made the modern world.” Rather, he confronts his readers with a strong statement – that what we think of as fundamentally modern, and therefore inherently human-centric, is the result of millennia-long inspiration from, cooperation with, and fight against insects. Our music, art, clothes, food, and science were never always exclusively ours, for we owe nature and its tiny beings a huge debt. The book concludes with a critique of another key feature of modernity: rather than accepting the naïve belief that somehow people will find a way to leave nature behind, we should resume one of our longest human traditions – listening to insects.

Atar David is a Ph.D. student in the History department at UT Austin, interested in the social, economic, and environmental history of the modern Middle East, with special attention to agricultural policies, commodities, knowledge production, and food provision policies. He is currently working on the circulation of agricultural commodities and their cultural networks throughout and beyond the eastern Mediterranean during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Together with Raymond Hyser, Atar founded the “Material History Workshop” – a bi-monthly graduate workshop centered around material culture. You can read more about the workshop here: https://notevenpast.org/uts-material-history-workshop/

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.