In Wild by Design, historian Laura Martin points to an irony at the heart of our contemporary ecological moment: in the face of human-made threats to the earth’s biosphere, it is only through further intercession into the workings of nature that humankind may remediate the harm that it has already caused. The notion that through conscious action, people have the potential to revivify or enhance natural systems is not, however, new. The assumption rests at the heart of the field of ecological restoration, whose history within the United States during the 20th century Martin seeks to recount.

Martin writes that historians have typically presented the history of 20th-century environmental management as a duel between environmental conservation and preservation. The former asserts that certain designated lands should be actively managed to guarantee the long-term availability of economically desirable natural resources. Environmental preservation, on the other hand, has sought to protect lands from any human footprint whatsoever. The logic of ecological restoration has long existed as a middle ground between these two poles, but its history, when it has been written of, has been traced back only as far as Aldo Leopold’s 1949 Sand County Almanac. In her book, Martin casts her gaze farther down the well of the past to the early 1900s, and beginning there, she traces a deeper and longer history of ecological restoration in the United States.

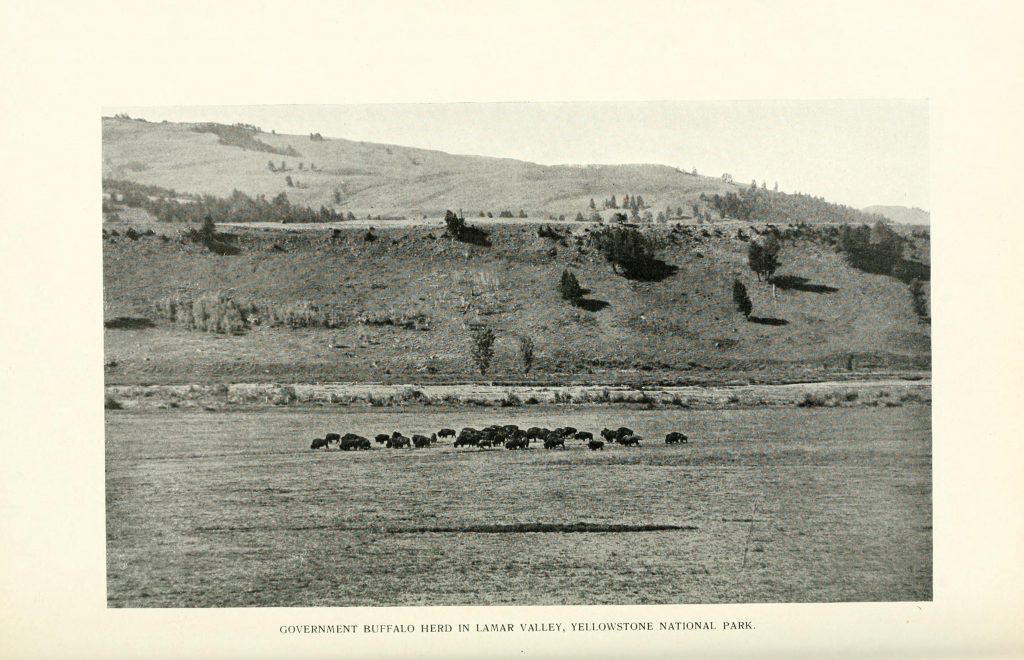

Martin begins her narrative with the American Buffalo Society in the early 20th century and its ambition to create game reservations in order to repopulate portions of the Great Plains after they had been depleted of buffalo. From there, Martin advances chronologically up to the present moment. She concludes her monograph with a discussion of the practice of off-site mitigation, the contemporary approach to minimizing environmental harm that attempts to compensate for destruction done to one ecosystem by restoring another. As a whole, the book traces how efforts to revitalize United States wilderness areas have evolved from attempts to restore only a single species to now much grander schemes that aim to guard the resiliency of entire ecosystems. Martin successfully shows in clear prose how ecological restoration evolved from the pursuit of many small, private organizations into an institutionalized scientific field whose knowledge shapes the majority of federal ecological management policy today. Martin reconstructs this history by working through government documents, published and unpublished scientific papers, news clippings, and other sources.

As Martin weaves her narrative together, she is at pains to show how the evolving understandings of nature’s workings that lay at the heart of restoration efforts interfaced with contemporary material, political, and cultural circumstances. Thus, Martin emphasizes how the studies and conceptual frameworks that have advanced ecological restoration as a field have also benefitted from and furthered the harm done to historically oppressed groups within the United States. In addition, Martin shows that at the heart of ecological restoration’s history lie shifting understandings of what constitutes “wildness” and frequent debates around what should be the baseline against which an ecosystem’s current health is measured.

Martin’s ability to construct narratives from primary sources and, in the process, chart an intellectual, political, and cultural history of ecological restoration is extremely impressive. However, as is typically the case with histories that cover long lengths of time, any one of her chapters feels like it could be expanded into its own book. Furthermore, in limiting its scope to the United States during the 20th century, Martin’s work begs the question of whether the history of ecological restoration can be geographically and temporally broadened beyond one country.

Finally, Martin’s narrative focuses exclusively on the knowledge and actions of an extremely limited number of actors and official institutions. Given her concern with environmental justice and the deleterious effects that restoration efforts have had on oppressed groups, it is curious that Martin does not devote more space to recovering their voices. Ultimately, the book invites a richer genealogy of the knowledge and experiences that fed and were informed by the development of ecological restoration.

Such comments are, however, not meant to detract from the value of Martin’s work. Her book adeptly situates, both politically and culturally, the development of ecological restoration in the United States during the 20th century. Wild by Design constitutes a well-crafted, clearly written work defined by sharp analysis. As such, it is suited to everyone from informed general readers to specialists in environmental history and the history of science.

Gaal Almor is a 2nd-year PhD student in the History department at UT Austin. His research centers on questions of legal rights and epistemology in the early modern Atlantic.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.