Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War by Susan Lederer explores the production of medical knowledge through human experimentation and animal vivisection. Lederer’s contextualization of the subject and her well-chosen examples enlighten readers and allow us to explore the intersection between politics, economy, medicine, and, of course, issues of ethical and moral character. One of the core topics in the book is the debate between the arguments of vivisectionists and antivivisectionists, vivisection being the practice of operating on live animals for the pursuit of scientific knowledge.[1] Through this discussion, one sees that the debate between the advancement of science, the greater good of society, and concerns about causing harm to the most vulnerable characterized the dialogue about human experimentation and animal vivisection in the early 20th century.

Lederer considers three interlocking questions: why “did American physicians routinely perform non-therapeutic experiments on their patients?” and “who served as the subject of these experiments and what risks did they encounter?”.[2] These questions are essential to the historical significance of the book. Although the Nuremberg trials generated awareness of human experimentation and the consequences it could have while also establishing a set of rules and regulations, we cannot understand human experimentation without first understanding what happened before these trials. As Lederer put it, the Nuremberg trials are not the start of human experimentation but, instead, part of it.[3] That is why it is valuable to understand human experimentation before the Second World War. It allows us to understand the influence of technological developments and historical events like the X-ray and the Great Depression on what research is today. This is one of Lederer’s main arguments, which she addresses in the introduction and chapter one.

The second chapter focuses on the claim that human experimentation must be looked at in the context of animal protection.[4] According to Lederer, antivivisectionists argued “it is not a question of animals or human beings, it is a question of animals and human beings”[5], showing how concerns for human experimentation started when the public became worried about animal welfare. The main argument was that “no progress in medicine… was worth the pain inflicted in laboratories by physicians and physiologists”.[6] Starting in 1866 with the establishment of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) by Henry Bergh and, later, the creation of various societies for the protection of children in New York and Pennsylvania in the 1870s, concerns over human experimentation were characterized by a preoccupation over those who were most vulnerable and did not have a voice.[7] These ideas circulated within the context of Darwinism, which fostered wider “acceptance of human and animal kinship”.[8]

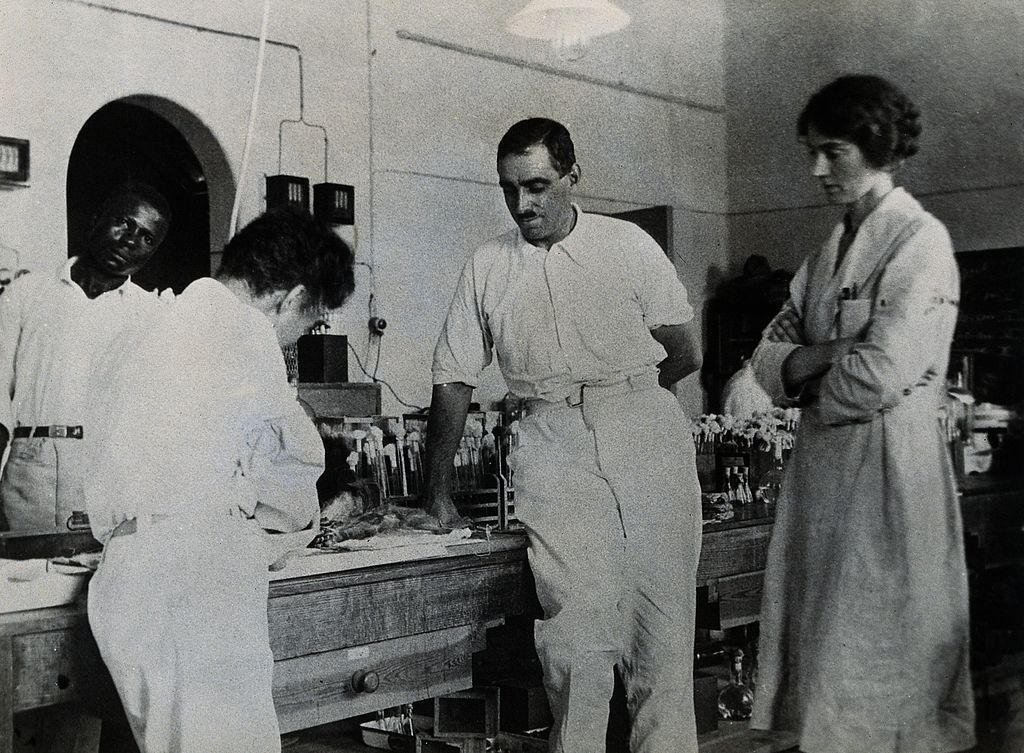

In chapters three and four, Lederer poses a debate between the ideas of vivisectionists and antivivisectionists.[9] She refers to Hideyo Noguchi’s experiments, where healthy children and hospital patients were used to develop a luetin diagnostic test for syphilis.[10] She also talks about Arthur H. Wentworth’s “experimental tapping of the subarachnoid space,” which, according to Wentworth himself, caused “momentary pain” and “some children to shrink back and cry aloud”.[11] These types of experiments—which inflicted pain among vulnerable people like children—caused controversy among antivivisectionists. For example, Diana Belais, the president of the New York Antivivisection Society, claimed that medical knowledge was placed before the wellbeing of the most vulnerable. She along with lawmakers, like Republican senator Jacob H. Gallinger, tried to pass laws regulating vivisection.

Meanwhile, in addressing vivisectionists’ arguments, Lederer talks about the American Medical Association (AMA) and Abraham Flexner’s survey of medical education, Charles W. Eliot’s reforms at Harvard Medical School, and the surge of research as the gold standard for creating medical knowledge. [12] Her sources rely on public statements from William H. Welch, the dean of the Johns Hopkins Medical School, and William W. Keen, the president of the AMA from 1899 to 1900. In contrast to antivivisectionists, vivisectionists’ main argument was that physicians had the obligation to generate medical knowledge, “to heal the sick, to check disease and to prevent death”, all of which could be achieved through vivisection and by having fewer restrictions in the law.[13]

The author also discusses issues that, despite being interesting because of their historical relevance, are incredibly heartbreaking. In chapter five, she delves deeper into the use of the most vulnerable—namely children, prisoners, soldiers, the poor, and those socially marginalized—as subjects for human experimentation. Experiments like those performed by J. Marion Sims on “black female slaves… to test his discovery of a repair for vesico-vaginal fistula”[14] are disturbing because of the intersection between social and political conditions with medicine. However, this discussion could have benefitted from a more in-depth discussion of race, social hierarchies, and inequality. Although Lederer used sources like articles from the Journal of Experimental Medicine, quotes from multiple figures, extracts from the magazine Life, and statements from the American Humane Association, she could have included a more human perspective from those who were experimented on, especially since the history of medicine deals with emotions and not just bodies and medical knowledge. Chapter five’s focus on the subjects of human experimentation introduces sub-arguments related to the issue of consent and whether we can justify experimentation on people whose consent cannot be obtained (like children) or is dependent on political or economic factors.

Despite debates on the ethics of human experimentation, chapter six demonstrates that research and “the discovery of insulin, sulfa drugs, and new treatments for pernicious anemia” eventually helped inspire confidence in medical researchers and doctors.[15] They began to be seen as heroes, as “those who survived their bouts with laboratory-acquired infections earned praise”.[16] There is a special mention of Walter Reed—who proved yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes—and Jesse Lazear—who was in Reed’s group and died from yellow fever as a result of self-experimentation.[17] This conclusion allows readers to see how research “became an integral part of [the] academic medicine”[18] and how it was influenced by everything that was discussed in previous chapters, further illuminating the historical relevance of the book.

Lederer’s book brilliantly explores what human experimentation was like before the Second World War by making reference to important figures like William W. Keen, William H. Welch, Diana Belais, and Jacob Gallinger and using sources like extracts from scientific journals and quotes from those involved. It is enlightening to read as it gives readers an insight into the arguments of both vivisectionists and antivivisectionists. Also, the idea that human experimentation cannot be understood without knowing what happened before the Nuremberg trials is valuable because the history of human experimentation does not have a beginning or an end: it is embedded in an ebb and flow of political, economic, and social circumstances. This book should be read by anyone who seeks to understand the complexities behind human experimentation. It is through books like this that we become aware of the implications of the creation of scientific knowledge and better understand ourselves as humans.

Juliana Márquez is a sophomore at the Johns Hopkins University majoring in Molecular & Cellular Biology. She has always been interested in the connections between epistemology and history. Since taking a class on the History of Modern Medicine, Juliana immediately found a passion for understanding how scientific and medical knowledge is created. She hopes to use this understanding to have a more human-based approach to science.

References

Goodman, Jordan, Anthony McElligott, and Lara Marks. “Making Human Bodies Useful: Historicizing Medical Experiments in the Twentieth Century.” Essay. In Useful Bodies: Humans in the Service of Medical Science in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

“vivisection.” In Concise Medical Dictionary, edited by Law, Jonathan, and Elizabeth Martin. : Oxford University Press, 2020. https://www-oxfordreference-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198836612.001.0001/acref-9780198836612-e-10814.

Lederer, Susan. 1995. Subjected To Science: Human Experimentation In America Before The Second World War. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

[1] Jonathan Law and Elizabeth Martin, “vivisection”, 2020

[2] Susan Lederer, Subjected to Science, XV

[3] Jordan Goodman, Anthony McElligott and Lara Marks, “Making Human Bodies Useful”, 3

[4] Lederer, XV

[5] Lederer, 101

[6] Lederer, 42

[7] In this chapter, Lederer alludes to the heartbreaking case of Mary Ellen Wilson, a 9-year-old girl who got beaten by her stepmother, as a catalyst for a growing concern for children and the creation of societies that cared about the wellbeing of the most vulnerable; Lederer, 28

[8] Lederer, 30

[9] Since there are various perspectives around human experimentation, Lederer does not only have one central argument. Instead, she addresses the perspective of both sides to contextualize human experimentation as a whole and go deep into what human experimentation was like before the Second World War.

[10] Lederer, 83

[11] Lederer, 62

[12] Lederer, 54-55

[13] Lederer, 100

[14] Lederer, 115

[15] Lederer, 126

[16] Lederer, 130

[17] Lederer, 18

[18] Lederer, 127

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.