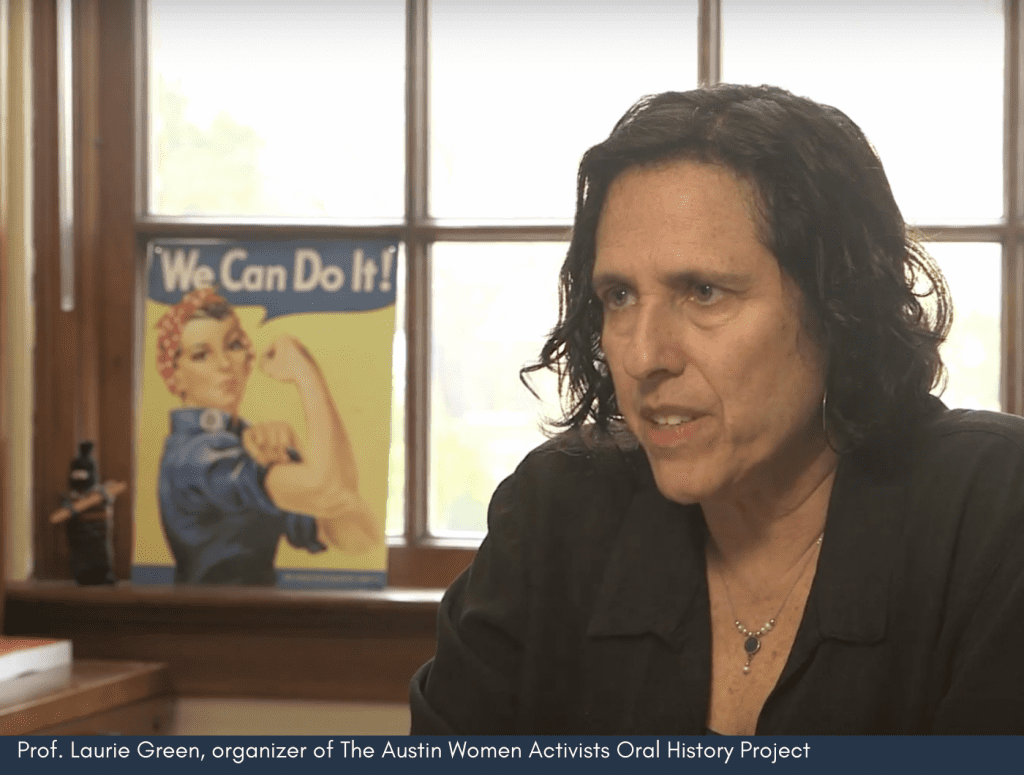

By Laurie Green

Since 2017, undergraduate students in my postwar women’s history seminars have had the unique opportunity to engage in intergenerational dialogues with women who were student activists at the University of Texas and the surrounding community during the 1960s and 1970s. As part of the Austin Women Activists Oral History Project, they have conducted professional-quality oral histories with roughly 30 white, Mexican American, and African American women who helped transform the UT campus into one of the largest and most significant hubs of student activism in the U.S., and helped invigorate a range of off-campus movements. These women activists agreed to donate their interviews to the Briscoe Center for American History, one of our many partners in the project. For Women’s History Month this year, the Briscoe is launching the Austin Women Activists Oral History Collection, a permanent digital collection that includes audio files, transcriptions, photographs, and additional documents that women have donated.

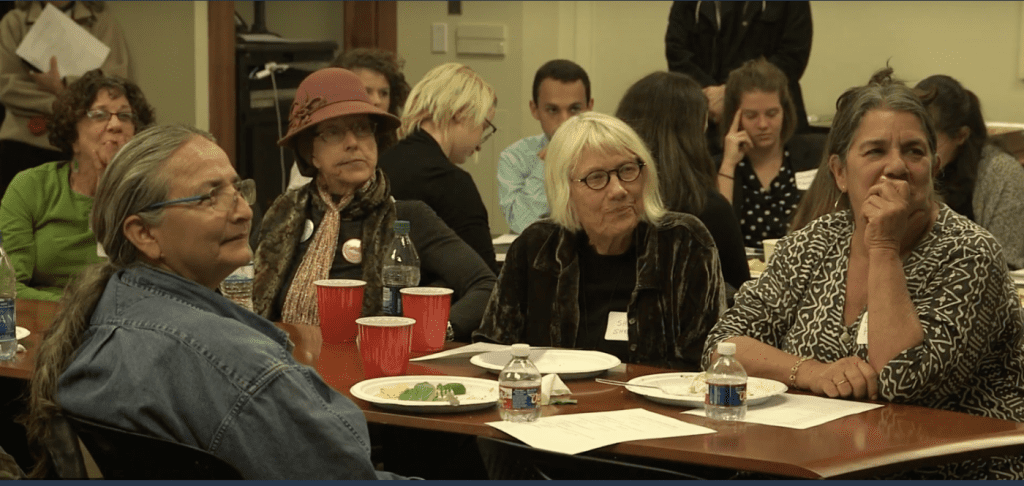

An extraordinary aspect of this project has been end-of-semester public gatherings at which students have presented their work to the women they interviewed, along with other students, faculty, and staff members from units on campus with which we have partnered. On December 14, 2017, for example, 18 students and most of the 21 women they interviewed came together for a dinner of enchiladas and history. The students’ presentations inspired a remarkable dialogue – not so much a walk down memory lane as an engaged discussion about how to interpret the activists’ own history. Based on footage from that event, Life & Letters media specialists Rachel White and Allen Quigley, at the College of Liberal Arts, produced Fight Like a Girl: How Women’s Activism Shapes History, a documentary film that Ms. Magazine also picked up for its online site.

As rewarding as this experience was, the public event held on May 17, 2019, “Pecha Kuchas and Pastries,” broke away from the format of conference-style research presentations. Students still had to develop their own interpretations of the history discussed by their interviewees, but instead of writing long research papers they created Pecha Kuchas. What’s a Pecha Kucha? It’s a PowerPoint-like presentation comprised of 20 slides (which advance automatically) and 20 seconds of narrative per slide [see links below]. The results might look simple, but they’re challenging for a historian. You have to distill your argument down to its essentials, keyed to images that enrich but don’t distract from your point on each slide. The “Pecha Kuchas and Pastries” public event drew about 40 people, some of whom were already veterans, either interviewees or interviewers from 2017.

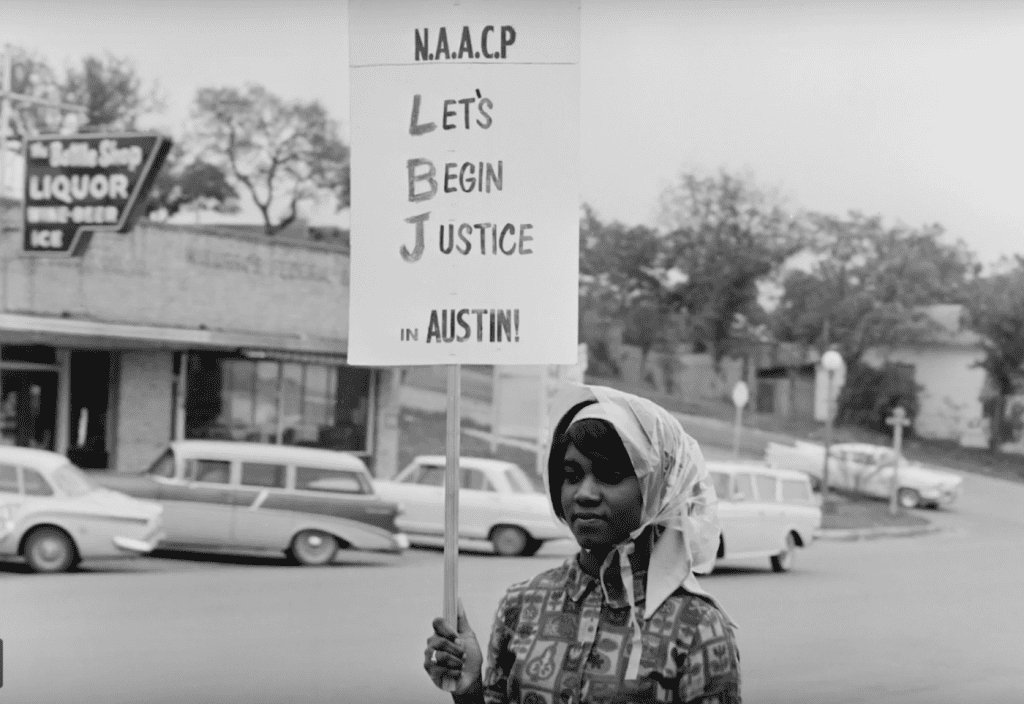

This format, which combined visuals and commentary, also provoked remarkable responses, captured on film by History Department videographer Courtney Meador. A Pecha Kucha about struggles by African American women students prompted 2019 interviewee C.T. (Carolyn) Tyler to describe her first semester at Kinsolving, just after the dorm was “integrated,” when she was the sole Black female in the dorm and assigned to what she described as a kind of lean-to shelter in the lobby. For a Black female student to room with a white female, the latter’s parents had to give their permission. Her story prompted 2017 interviewee Linda Jann Lewis to share her own experience as a first-year student in 1965, when she lived in Kirby Hall, a women’s dormitory at 29th St. and Whitis owned by the Methodist Women of Texas. The brochure described Kirby Hall as integrated Lewis remembers, yet the 250 residents included only six Black women, two roommates per floor. Lewis lived in the basement.

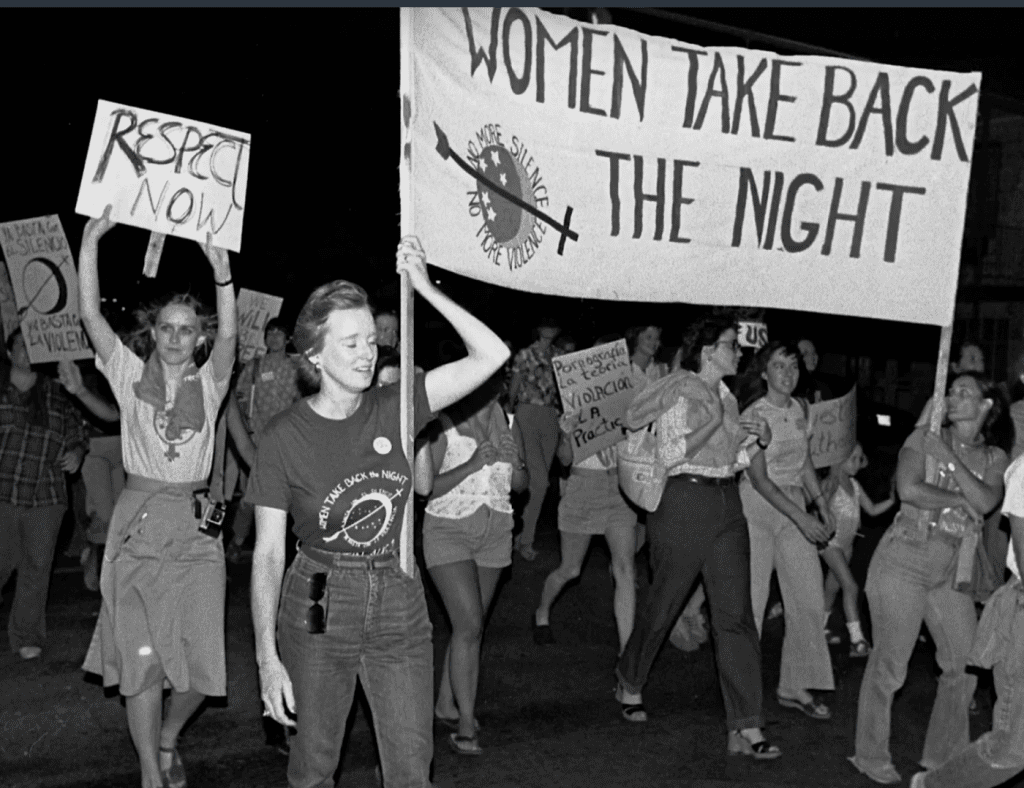

Two Pecha Kuchas addressed the origins of “women’s gay rights” and the Austin lesbian community, based on interviews with women who, in turn, brought a few other friends from the 1970s to the event. These two presentations pieced together a history of activism and the creation of the Austin Lesbian Organization, Women’s Liberation, and women’s institutions such as Bookwoman bookstore (still in existence), the Safe Place shelter, women’s music venues, bands, and a recording studio. “I’m proud of my generation,” one woman declared. Emma Lou Linn, a 2017 interviewee, described getting some of the first gay and lesbian protective ordinances in the country passed when she served on the city council. This history was previously unfamiliar to any of the students.

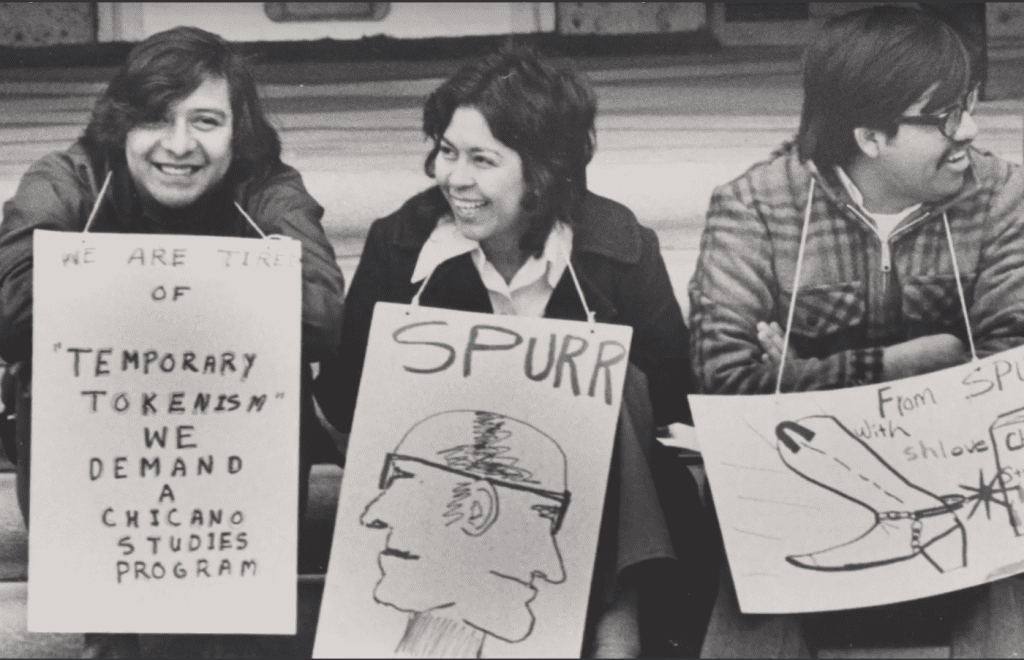

Cynthia Perez, co-owner with her sister of La Peña, a downtown Latino cultural gallery and a 2017 interviewee, initiated another unexpected conversation after watching a Pecha Kucha that delved into Chicano/Black relations at UT. She recounted the inspiration she and other Chicana/os found in Black Power student activism at a time when she was a student at University of Houston before transferring to UT. “We rode the coattails of the Black students,” Perez declared. That perspective persisted when she arrived in Austin and, in 1975, participated in an occupation of the Tower to demand Chicano and African American student and faculty recruitment, as part of United Students Against Racism at Texas (USARAT). Another participant asserted that the antiwar movement at UT brought everyone together. Others vividly recalled a quite different shared experience: the Charles Whitman shooting from the Tower in 1966.

It did not take arm-twisting to convince these women to tell their stories; many emailed back the same day saying they wanted to participate in the project. Collectively, they believe that the history of this activism is crucial for the current generation of students to understand, and are disturbed that it has remained nearly invisible in national narratives of women’s liberation, civil rights, campus antiwar struggles, Black Power, Chicano liberation, gay and lesbian activism, and other movements. For the students, it’s fair to say that these interviews have challenged every preconception they brought to the table based on previous reading. None was aware that in 1956 UT became one of the very first public universities in the South to desegregate its undergraduate student body, but refused to allow Black women students to live in the regular dormitories until 1965, and only after years of protest. Likewise, they did not anticipate learning that the real beginning of the 1973 Roe v. Wade case was not in Chicago or New York, but among students on the UT campus, the flagship university of a conservative state.

The Austin Women Activists Oral History Project – set to become a history capstone course in Spring 2021 – reflects approaches to “experiential learning” encouraged by the UT Faculty Innovation Center (FIC). The FIC, along with proponents elsewhere, delineates several components of experiential learning, including preparation, autonomy, reflection, bridges, and a public face. As a history professor, I understand experiential learning as a form of pedagogy aimed at helping students value their own minds by working both independently and in collaboration with other students to rethink assumptions about history and to create lasting public products with the capacity to influence others. In developing the Pecha Kucha project students had the advantage of both working in pairs on their interviews and Pecha Kuchas, and working independently on papers that focused on the broader historical context of their interviews, and articulated research “problematics” – i.e., what one is arguing, how it destabilizes previous understandings, and why their project matters.

Besides the teamwork in the classroom, the creation of the Austin Women Activists’ Oral History Project represents collaboration with community activists and alumnae off campus, and many units on campus: the History Department, the Briscoe Center for American History, the Nettie L. Benson Latin America Collection, the Perry-Casteñada Library, the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, the Faculty Innovation Center, University of Texas Captioning and Transcription Services, Life & Letters and the College of Liberal Arts.

A key component, suggested by Anne Braseby at the FIC and Margaret Schlankey at the Briscoe Center for American History, was reflection. In their papers, students wrote about both difficulties and breakthroughs they experienced. Several felt nervous going into their interviews, because they had never conducted an oral history before. One student said she felt frustrated at the lack of scholarship on “black women’s histories at Southern universities, which shows the project’s importance but made the context harder to find.” A graduating senior wrote that he “expected the interview and my research just to be littered with dates and facts, but the reality was that this assignment was full of life and felt important.” At the same time, it “made [him] feel as if [he] had done nothing in my time here as far as activism.” A Mexican American student wrote that her interviewee’s “point of view was very interesting, when she told me that she did not care that the only reason why she was accepted into the university was due to her race and the university’s quota for minority students.” This was “very different to the views that many students have today.” And one of the students who interviewed Erna Smith, who currently teaches in UT’s School of Communications, wrote that “learning about her time at the University of Texas, allowed me to see the campus I walk every day in a new light. Opening myself up to learning this was challenging, as I am often going into projects searching for the answer I want. However, my research and the interview created new questions that allowed me to dive deeper into topics I never realized I ignored in the past.” [Underlining in originals]

For more on this project, including tapes and transcripts of of the interviews, see the dedicated page for THE AUSTIN WOMEN ACTIVISTS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT on the website of the Briscoe Center for American History.

PECHA KUCHAS

Serena Bear and Zoë Marshall

“NAP, AABL, and Black Power at UT”

Shianne Forth and Amber Dey

“Setting the Record Straight: Gay Liberation was More Than Just Stonewall”

Sara Greenman-Spear and Wilson Petty

“The Glo Dean Baker Gardner Experience: How Black Women Transformed Social Organizations into Political Ones”

Michelle Lopez and Carson Wright

“Hello to All This: How Invisibility Uncovered the Austin Lesbian Feminist Movement”

Sasha Davy and Brittney Garza

Justice Warriors: How African-American Women Fought for Equality at UT.”

Taylor Walls and Elizabeth Zaragoza-Benitez

“Chicana Revolutionaries: A Rising Voice for Social Change at UT, 1960s-1970s”

(COMING VERY SOON!)

Photo Credits:

Pecha Kuchas reproduced with permission. Photos are frame captures from “Fight Like a Girl,” College of Liberal Arts, UT Austin. Historical images in that film come from The Texas Archive of the Moving Image and the Briscoe Center for American History.