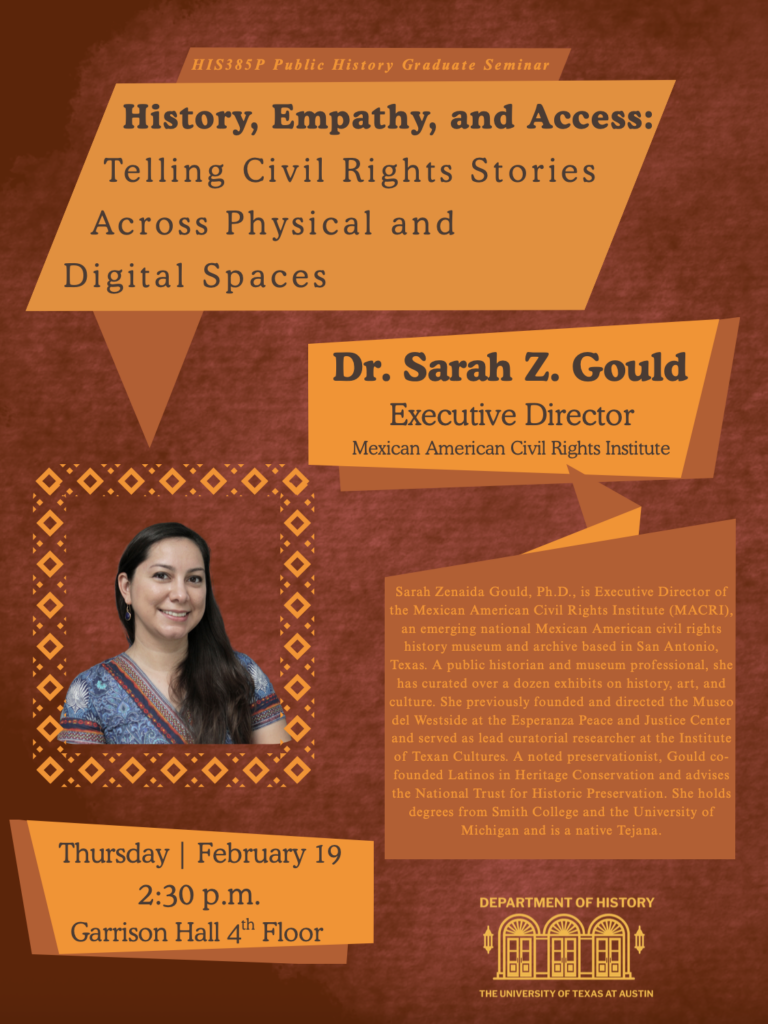

MACRI Executive Director Dr. Sarah Z. Gould will be at UT Austin on February 19th, 2026. You can find more information about her talk at the end of this article.

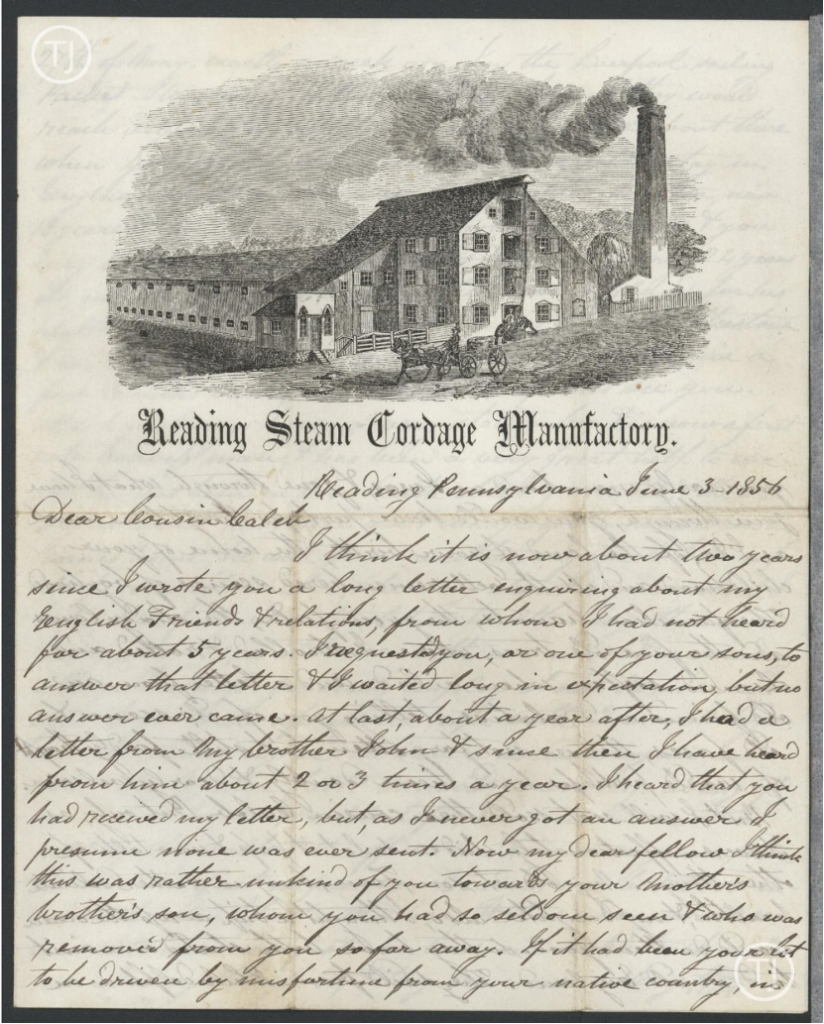

Nestled in the heart of San Antonio, Texas, just west of downtown, lies the Mexican American Civil Rights Institute (MACRI), an organization dedicated to chronicling and sharing the history of Mexican American civil rights in the United States. It lies within the field of public history, which moves history beyond university classrooms and academic journals, bringing it into museums, community spaces, and online platforms where the public can engage with it directly. On October 22, 2025, I sat down with its executive director, Dr. Sarah Zenaida Gould, to talk about the organization, its beginnings, and its mission.

“2018 and 2019, these were two big anniversary years in San Antonio,” Gould said, explaining that the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Hearings had been held in December of 1968 in the city. The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights was established in 1957 by the federal government to address issues like discrimination that concern race, ethnicity, and culture in the United States. The 1968 hearing in San Antonio was “one of the first times that the federal government officially heard testimony about experiences of discrimination that Mexican Americans had throughout the Southwest” specifically. The hearings occurred just a few years after the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which were aimed at reducing discrimination for African Americans and set a precedent for civil rights to later be expanded to other minority groups. A conference was held in November 2018 in San Antonio to commemorate the event.

This was followed by a second conference in 2019 for the 50th anniversary of the Edgewood school walkouts, an event that took place in May of 1968, when over 400 Mexican American students protested for better and more equitable education by walking out of Edgewood High School in San Antonio. The conferences were significant as people involved in both the walkouts and the commission hearings gave testimonies about their experiences and how the events got more people involved in the Chicano Movement, politics, and community activism. These back-to-back conferences reignited interest in Mexican American history and, more importantly, in how to preserve it.

For Gould, the conference was not just a spotlight on San Antonio’s Mexican American civil rights history, but also a race against time. “At the next big anniversary,” she warned, “most of those people would no longer be with us.” The question was simple and urgent: “how do you keep that history alive?” That question ultimately led to the creation of MACRI. The initial plan was just to create an exhibit that depicted Mexican American civil rights icons in San Antonio, but support from the city council, Mayor Ron Nirenberg, and the community was much more substantial than anticipated. Gould explained that it was at a cultural moment when a lot of people were thinking about equity within history. “One thing that we kept hearing from city council members and members of the public was why haven’t we had this before?”

National Farm Workers Association protest buttons. Source: Wikimedia Commons

MACRI began organizing itself with funding from the city and was officially incorporated on May 29, 2019. Gould was involved from the beginning and was asked to step into the position of Executive Director in 2020, partially to help the organization transition into a virtual space during the pandemic. This was when MACRI first began to flourish in its engagement and reach, creating a community despite everything happening in the world at the time. They began by having conversations about Mexican American civil rights in online events with historians and other experts, and noticed that over half the viewership was from outside the San Antonio area. “They were from all over,” Gould said. “That was particularly exciting.” Even when MACRI began to transition to having mostly in-person events as the pandemic eased up, they still received emails from people across the country, asking that virtual involvement remain in some form so that they could continue to participate in Mexican American history.

One of MACRI’s goals is to make San Antonio’s role as the birthplace of Mexican American civil rights to the general public. This is already happening among guests who attend MACRI’s in-person and virtual events, celebrating moments when people stood up against injustice. Gould discussed how “for so many people, this history is part of their living present moment,” as they often had a personal connection to the stories MACRI was telling. Still, others were learning about it for the first time. Nearly all wanted to learn more.

MACRI hosts a number of different events, including talks and exhibits with historians, activists, and more. These usually have themes, such as civil rights trailblazers or landmark court cases involving Mexican Americans. Their September 27 to November 26, 2025 exhibit was on Cisneros v. Corpus Christi ISD, an important civil rights case that extended school desegregation from Brown v. Board of Education to Mexican Americans. Brown occurred in 1954 and Cisneros in 1970. “So it takes a while for these things to happen,” Gould said. “You have to have those precedent-setting cases so that you can move the legislation forward.”

Gould is already planning events well into next year, which will be the 250th anniversary of the United States. The events will aim to “[make] sure we’re inserting Mexican Americans into how we understand America.” They will start with Spanish colonial Texas and will move forward in time over the course of the year. The events and exhibits will include discussions of important court cases involving due process, and in the summer of 2026 they will host screenings for the 30th anniversary of the Chicano! History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement documentary series that originally aired on PBS in 1995. Gould will also be visiting a number of universities throughout the state, including the University of Texas at Austin, where she will be sharing more about what MACRI does with current students.

In the old Mexican market area just west of downtown San Antonio. Source: Wikimedia Commons

When creating their in-person exhibits, MACRI tries to identify a scholar for whom that area of history is their subject matter expertise, whom they consult with. Their first exhibit was based on Dr. Cynthia Orosco’s biography Pioneer of Mexican-American Civil Rights: Alonso S.

Perales for their trailblazers series. For the current exhibit on Cisneros, MACRI worked with Dr. Isabel Araiza at Del Mar College in Corpus Christi. Their goal with each project is to make the information accessible. “The idea with most exhibits is to give people just a slice of what that is, so that they have a basic understanding,” and then if they are interested in learning more, MACRI points them to more resources.

MACRI has also done exhibits that were created through collaborations with local schools. Earlier in 2025, they did an exhibit for Dolores Huerta’s 95th birthday. Huerta is a Mexican American civil rights activist who is best known for being the co-founder of the United Farm Workers Association, a labor rights organization, alongside Cesar Chavez. MACRI’s exhibit on Huerta was created by sending out a call for art submissions to schools across the San Antonio area. “I have to thank the teachers whom we sent this out to, because clearly they talked to their kids about who she was,” Gould commended. “A number of them incorporated quotes from her into their artwork, and in their artist statement… You could just tell that they had been really reflecting on ‘Why does she matter to me?’ ‘Why does she matter to my family?’ ” She praised the teachers multiple times, stating that MACRI had only given them parameters and a brief synopsis of Huerta’s life, but she “could tell the teachers went above and beyond what we provided them, because the students clearly put a lot of thought into what they were drawing or painting, and connecting that to her life.” This was part of an initiative to get students more involved with history museums, which tend to cater to and attract an adult audience, unlike art and science museums. But the success of the project showed that it is far from impossible to get children to engage with history.

Gould also discussed the challenges and opportunities that working beyond academia brings. The most difficult thing she cited was the lack of infrastructure available to her and the other employees at MACRI, including things like access to research databases. But there are positives too, the most prominent of which is the freedom from constraints of university timelines. Historians who work for universities are tied to both the academic calendar and making sure they are hitting the goalposts in their careers, such as tenure review. But as a public history organization, MACRI can do things on its own time.

Still, Gould has hope for bridging the divide between the two fields. “I would love to see more collaboration between universities and people who are independent historians outside of academia,” Gould said. “Because you know, the universities do have resources that public historians could really benefit from, and public historians do have typically… connections to real grassroots-type history that could be of a benefit to students to know about.” With its exhibits, events, and media outreach, MACRI is working to bridge the gap. But to reach this goal, universities and historians within academia have to do their part to connect with public history as well. By remaining dedicated to continued collaboration between the public, academics, and everyone in between, MACRI is a model example of what these types of connections can look like, reshaping how American history is told.

Kara Alexandra Culp is a current history PhD student at UT Austin, focused on Latina/o history in the 20th-century United States. Her dissertation project aims to explore the effects of education policy and law on Latina/o immigrant students in the borderlands in the 1970s and beyond.

Sarah Zenaida Gould, interview with author. October 22, 2025.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.