Sitting in a humble home in Huehuetenango, Manuel Alvarez told me the story of his near execution at the hands of the Guatemalan military. It was 1982 when the soldiers, under the direction of a Pentecostal dictator, first shoved his helpless body to the pavement and then placed an ice-cold muzzle against his back. “They told me that I better believe in Jesus,” he said softly, “because only Dios could save me from their bullets.” While Alvarez miraculously survived this encounter, he returned home that night deeply disturbed by the soldiers’ threats. He knew that his country’s military frequently killed, mutilated, and disappeared civilians. Yet he never before experienced how swiftly his body could be seized without repercussions or retribution. If he were to die on that pavement, he imagined, his family was unlikely to identify him and they would be forever haunted by not knowing what happened. In the wake of this terror, Alvarez called his brother Felipe to his bedroom and asked him to tattoo both his arms, to identify his body if need be.

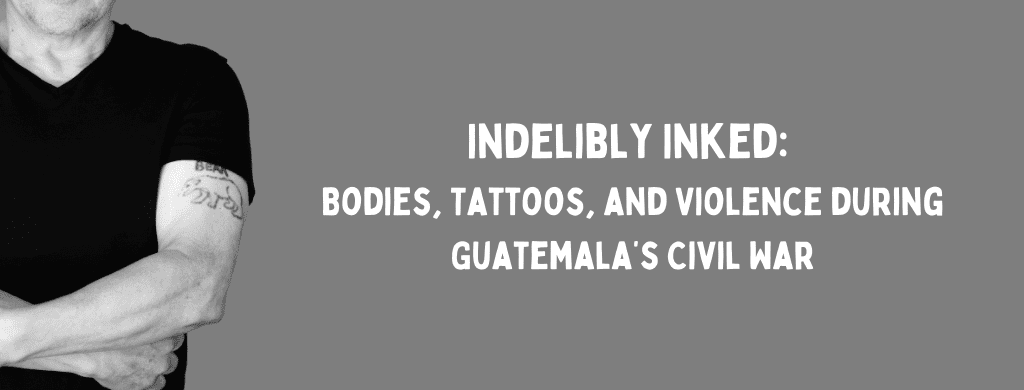

As Alvarez rolled up his tee-shirt sleeves, his brother cautioned him that marking his arms was “not going to be good.” Nobody carried tattoos during those days and Felipe worried that his older brother would be judged harshly at church that Sunday. Despite this warning, Alvarez pressed his younger sibling to gather a pen, black ink, and a needle from the kitchen. Felipe listened, returned, and hesitantly began to sketch a blurry outline of a bear on his brother’s left arm. At that moment, Alvarez did not care what the tattoo was of, he simply implored his brother to “just do something here.” After the first tattoo was finished, Alvarez thought about what other indelible ink could identify him in the event of his death. He considered his childhood nickname, “canche,” which his friends lovingly called him because of his unusually light hair. He remembered the American missionaries he befriended in the 1970s who called him “blondy,” canche’s English variant. Following the soldiers’ threats to his body, it was this name that Alvarez felt could best distinguish him if he were discovered dead on the streets of Huehuetenango.

After this haunting evening, Alvarez’s brother also went on to tattoo a small circle on one of his own bare knuckles. His best friend Alberto, who was similarly menaced by the Guatemalan military, came over later to ask Felipe to brand his body. The young man requested an image of a wolf, or lobo in Spanish, which was his nickname throughout the town. During a time of ever-present violence in Guatemala’s western highlands, all three Huehuetecos decided to tattoo their own bodies.

In voicing this history, Alvarez prompts us not only to reassess our understanding of Guatemala’s bloody Civil War, but authoritarianism writ large. For one, his story lays bare the immense corporeal costs of the Guatemalan military’s counterinsurgency strategy. In deploying terror tactics to pacify the population, the ejercito (army) not only murdered thousands of civilians but prompted men like Alvarez to mark their own bodies. In this way, one may interpret Alvarez’s tattoo as participation in his own discipline, as the physical embodiment of the fear the government sought to instill. Alvarez even suggests this at the end of his testimony when he states that, looking back, “it was not really my choice because I just did it out of fear.”

However, if we understand Alvarez’s decision to tattoo as a direct response to the soldiers’ threats, his story elucidates the limits of state power. Where death squads in Guatemala repeatedly executed civilians and deprived their families of closure, Alvarez’s tattoo might have thwarted such efforts had he died. If the army killed him, or Felipe, or Alberto, their markings might have rendered them more recognizable to their families regardless of the military’s brutality. Their mothers and fathers could then recite the Lord’s Prayer and give them a proper burial. In this sense, Alvarez’s tattoo embodies rebellion against the Guatemalan government’s authority to deprive families of the ability to grieve. His indelible ink, even in death, may have prevented the state from terrorizing his people and denying them this right. By sharing his story, Alvarez not only reveals these bodily costs of war, but illuminates the power of a few, defiant marks.

Citations And Further Readings:

- Interview with Manuel Alvarez, December 28th, 2019, Huehuetenango

- Manuel Alvarez Tattoo, Photos by Jana Wallace. March 22nd, 2020. Los Angeles, CA

- Garrard, Virginia. Terror in the Land of the Holy Spirit: Guatemala Under General Efraín Ríos Montt, 1982-1983. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.