How can the life of an artisan who specialized in punchcutting and engraving help us shed light on “the idea of the Spanish Enlightenment”? Donahue-Wallace offers an illuminating perspective on the Enlightenment through the biography of an expert medal caster, Jerónimo Antonio Gil, whose career took him from provincial Zamora to Madrid and ultimately to Mexico, where he became the founder of the first royal academy of the arts in the New World.

Had Gil lived in the seventeenth century he would have become a painter, churning out religious canvasses in his native Zamora. Had Gil moved to Madrid, he would have become a criado (servant) for a stonecutter or a wood carver or an oil painter, never an artisan letrado (intellectual). When Gil left Zamora in the 1740s, however, he got a stipend to attend the new Academia de San Fernando in Madrid where he learned to cast dies for commemorative medals, to cut letter punches and counterpunches for typesetting, and to carve copper plates for engravings. He was also trained to master a literary and historical national canon in the vernacular. Gil got an education to copy the great masters but also to produce his own original designs in neoclassical style. In short, Gil was educated to become a civil servant, one of many officials in the Bourbon dynasty charged with creating a new specialized national print culture and regalist media. Donahue-Wallace explores the many medals, engravings, drawings, and typographic samples Gil produced in a career that spanned more than fifty years, twenty of which in Mexico.

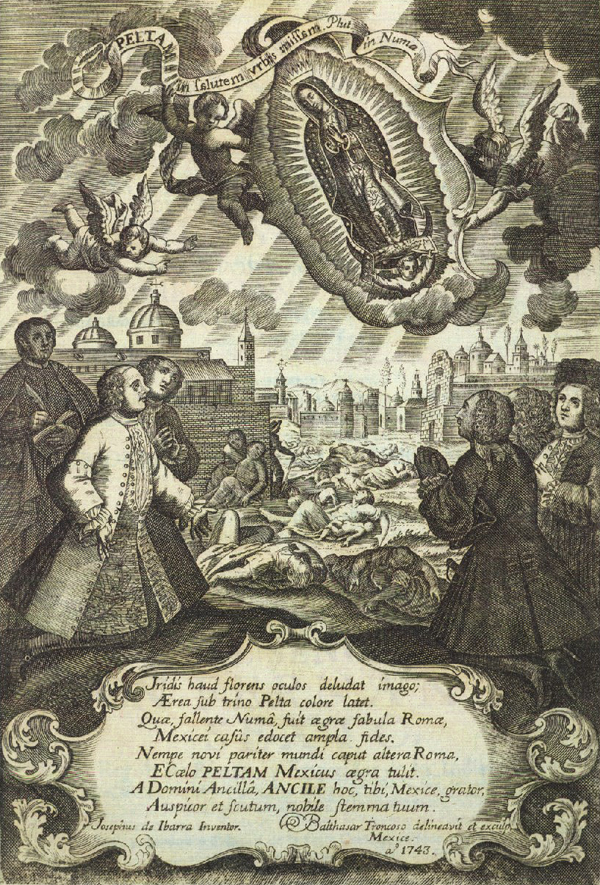

Donahue-Wallace uses Gil’s career to make several larger arguments. First, she demonstrates the newfound importance of print culture in mid-eighteenth-century Spain. An ancien regime that had long been centered on literacy and the pushing of paperwork suddenly realized that modernization, renewal, and geopolitical survival demanded a turn to print as reason-of-state. The Bourbon invested heavily in the training of artisans (either at home or overseas) to eliminate Spain’s secular dependency on the expertise of typographers and engravers from France and the Low Countries. The new culture of print pushed a “national” and regalist project via the promotion of historical, religious, scientific, and literary texts. Gil, for example, carved and designed many copperplates to illustrate collections of national architectural monuments, antiquities, and coins as well as to illustrate books of anatomy, engineering, religion, and literature (including editions of El Quijote and the Bible). Gil also designed dozens of commemorative medals and coins to celebrate the lives of monarchs as well as the myriad institutions these monarchs had created. Coins were not only currency but also non-ephemeral media to circulate like engravings.

Second, Donahue-Wallace shows that in the second half of the eighteenth century poor provincials could accumulate wealth, honor, and political power as artisans. Donahue-Wallace offers the biography of a metal caster, cutter, and engraver whose status did not come from originality and genius. Gil nevertheless became prestigious enough to direct a national art academy and wealthy enough to amass one of the largest private collections of paintings, books, scientific apparatus, and curiosities in late-eighteenth-century New Spain. A poor Zamorano punchcutter rose through the ranks of the state bureaucracy to achieve nobility and wealth.

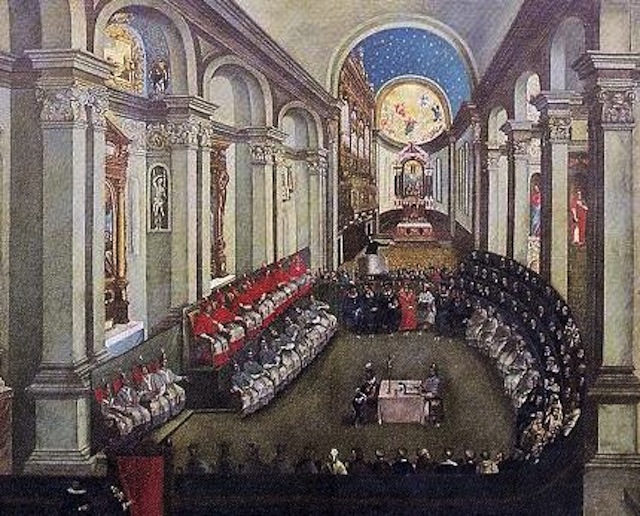

Third, Donahue-Wallace suggests that there was greater room for pedagogical innovation in Mexico than in Madrid. Donahue-Wallace follows Gil both as a student of the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid and as the founder and director of the Academia de San Carlos in Mexico. Both academies were named after the monarchs that decreed their creation (Ferdinand VI and his half-brother Charles III, respectively). San Fernando operated both as a public school to train painters, sculptors, architects, and engravers and as the recruiting space of apprentices for professors. The young Gil received a public education in the evenings at San Fernando, where teachers checked his drawing skills before live models, casts, or prints. During the day, however, Gil went to the household of the school’s leading printer-medal caster. Gil worked for almost a decade as the criado of Tomas Francisco Prieto, one of the teachers of San Fernando. To declare independence from Prieto, the master patriarch, Gil had to create an alternate network of patrons. When Gil went to Mexico to lead the Academy of San Carlos, he deliberately eliminated the master-criado traditions of San Fernando. Going against the authority of the professors of architecture, painting, sculpture, and engraving, Gil created in Mexico an academy in which masters could not recruit students as apprentices. Gil engaged in a twenty-year long battle, until his death, with second-tier Spanish artists who saw themselves entitled to use the academy to get pliant, skilled labor. Gil created an academy of art in Mexico in which teachers received large enough salaries to be expected to be full-time professors, not freelance agents in search of apprentices and commissions.

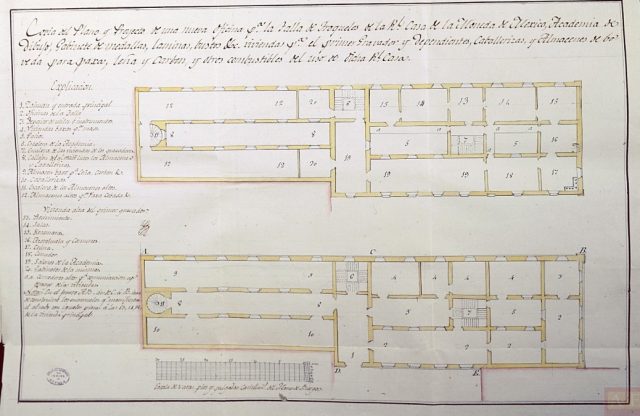

Fourth, Donahue-Wallace shows that Enlightenment modernity emerged organically out of the institutions of the ancien regime; it was not an outside competing force. The idea of a public sphere of circulating prints, for example, was a Bourbon strategic initiative. Artisans relied on the good will of patrons for employment, commissions, and success, not bourgeois anonymous market forces. Finally, those struggling to liberate the youth from the clutches of master-apprentice guilds behave like old-fashioned patriarchs themselves. Donahue-Wallace demonstrates that, for all the novelty of his pedagogy, Gil remained embedded in the patriarchal values of the ancien regime. Gil arrived in Mexico with the blueprints to build a mint school right next to the stables of the viceregal palace. He also arrived with an entourage of four students, two of whom were his own children. The original school immediately transmuted into the Art School of San Carlos, to train not only printers but also sculptors, painters, and architects. San Carlos went up as two-story elongated rectangular building, one-half of which was occupied by horse stalls and storage rooms for food, forage, and wood. The upper quarter was Gil’s residency, which included salons and cabinets for San Carlos’ official acts. The lower quarter held the school’s workshops and tool rooms. It also included four tiny rooms for criados. Gil kept his sons and assistants tied to his patriarchal control for some twenty years. For these four “students,” the Academy became a boarding school. As Gil’s criados they were not allowed to set up their own households.

Donahue-Wallace has written an important text on the relationship between artisans and the Spanish Enlightenment on both shores of the Atlantic. The book follows Gil and his artifacts in painstaking detail and offers a wide panorama of an ancien regime struggling to catch up while unwittingly devouring itself.

Kelly Donahue-Wallace, Jerónimo Antonio Gil and the Idea of the Spanish Enlightenment (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017).

Also by Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra on Not Even Past:

Magical Realism on Drugs: Colombian History in Netflix’s Narcos

Seeds of Empire, By Andrew Torget (2015)

Whose Classical Traditions?