By Huaiyin Li

Since the early twentieth century, Chinese intellectuals and political elites have written about China’s “modern history” with various, often conflicting, explanatory narratives. Looking back over the last century shows that historical writing on “modern China” has evolved primarily in response to the historians’ present concerns.

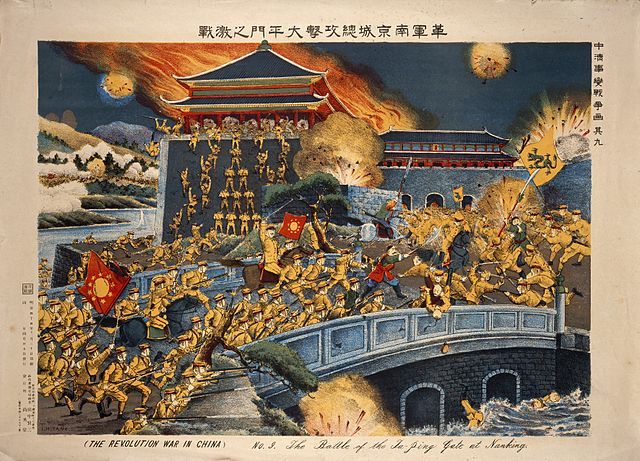

To write about modern China was to trace the historical roots of the country’s current problems in order to legitimize their solutions rather than seeking to reconstruct the past as it actually happened. From the 1930s through the 1990s, two master narratives rivaled each other to dominate history-writing in China. One is the narrative of revolution, which tells modern Chinese history as the grand process of Chinese people engaged in a century-long struggle against feudalism and imperialism, beginning with the Taiping Rebellion in the mid-nineteenth century and culminating in the Communist Revolution in the 1920s through 1940s.

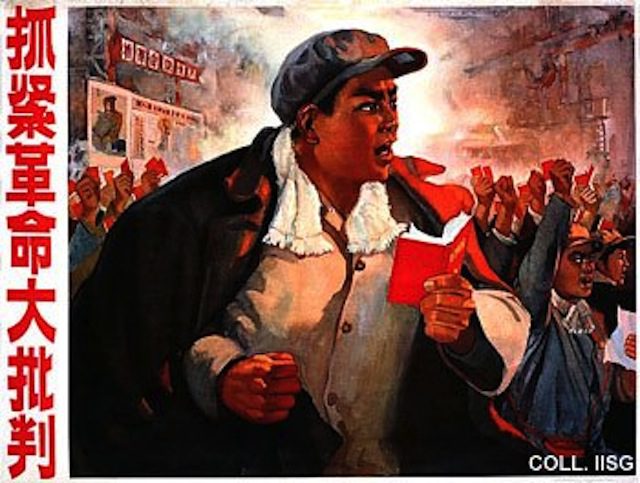

Cultural Revolution poster- Propaganda Group of the Revolutionary Committee of the Shanghai No. 3 Ink Factory, 1969 (Wikipedia)

This historical narrative centers on the economic and social changes brought about by the encroachment of foreign capitalism. It accentuates the worsening livelihood of the peasantry, the vulnerability of the emerging modern economic sector, and subsequently the necessity of a political revolution for China’s healthy development. It exalts collective violence against feudal and imperialist forces and downplays the role of reformist elites and foreigners in China’s progress. In this telling, modern Chinese history lead inevitably to the Communist revolution and China’s transition to socialism.

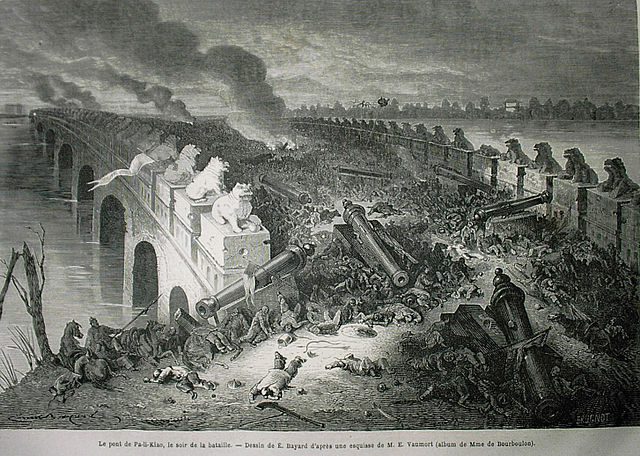

The other dominant narrative is the history of modernization, which is diametrically opposite to the revolutionary account. It sees modern Chinese history as the long-term transformation of China from an insulated, backward civilization into an industrialized and democratized society under the positive influences of the West and the reforms by enlightened elites. It necessarily leads China to the establishment of a capitalist system and Western-style democracy.

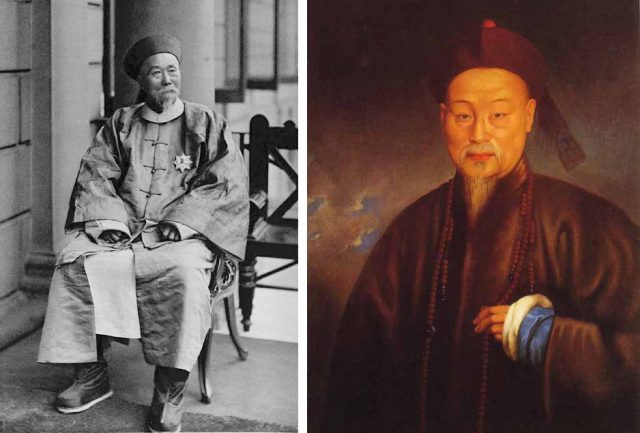

These two competing narratives give rise to contradictory accounts of individual events and assessments of historical figures. While Governor-General Li Hongzhang, for instance, was depicted in the modernization historiography as an open-minded statesman who was committed to China’s “self-strengthening” by borrowing from the West, the same person was denounced by the revolutionary historians as a traitor who was preoccupied with the aggrandizement of his own clique at the expense of China’s national interest. On the other hand, Commissioner Lin Zexu appears in the revolutionary narrative as a patriot because of his heroic acts of confiscating and destroying the opium from English traders, but the same figure is depicted in the modernization histories as an unrealistic, arrogant mandarin who cared more about his personal reputation than the security of the country.

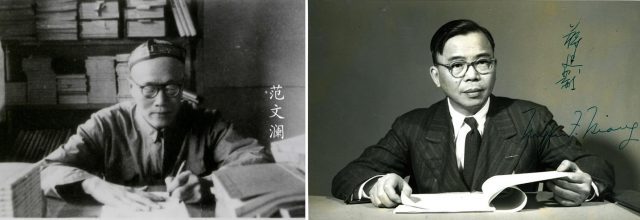

A fundamental problem with history writing in modern China, as these instances suggest, is the politicization and teleology found in both the revolutionary and modernization literatures. For the leading historians in twentieth-century China, whether affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party or the Nationalist Party, writing about the nation’s recent history was not for the purpose of reconstructing the past as it actually happened, but “using the past to serve the present” (gu wei jin yong). Historians reinterpreted the past in order to legitimize the agendas and goals of the political forces they favored. This was true for Fan Wenlan, the most famous historian of the Chinese Communist Party, and Jiang Tingfu, a leading Nationalist historian, in the 1930s and 1940s. It was also true for almost all of the Chinese historians in the Mao era, despite the resistance of a few who adhered to the principle of “objectivity” in history-writing at the cost of their lives during the Cultural Revolution. It was even true in the 1980s and 1990s, when modern China was reinvented to render support to the reform and opening up policies of the post-Mao leadership.

Since the late 1990s, Chinese scholars have increasingly lost their interest in the grand narratives revolution and modernization and instead have shifted their attention to social and cultural histories, in particular, the history of the subaltern. In the absence of a master narrative, historical writing has become increasingly “fragmented” (sui pian hua). The in-depth study of historical events at the micro level is often achieved without making sense of the new findings in larger contexts of historical developments and theoretical debates.

Three shots from the films made in the 1980s about Long Bow village: a bride, preparations for Lunar New Year, and a Catholic village doctor. One Village in China

To overcome the problems of teleological and fragmented history, I propose a new approach to rediscovering modern China, which I term as a “within-time and open-ended history.” It is “within time” because it looks at a specific event in modern China from the point of view of the time when the event was taking place, when different possibilities for the development of the event existed simultaneously, and when participants in the event were not as conscious of its results as were historians of a later period. It is “open-ended” because it rejects the teleological historiography of revolution or modernization, in which the “ending” of the history was clearly defined on the basis of ideological assumptions. Historical representation can be closer to the realities of the past only after we overcome the results-driven, teleological approach inherent to twentieth-century Chinese historiography; and it can be more meaningful only after we put the fragmented pieces of the past back into a larger whole.

Reinventing Modern China: Imagination and Authenticity in Chinese Historical Writing

University of Hawaii Press, 2013

For more reading on Chinese history click here.