In September 1935, Jimmie Lee Robinson and fourteen other Black Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers stationed at Palo Duro State Park in the Texas Panhandle wrote to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to protest their treatment in the CCC camp. “We work some time six days in a week,” they said, “and have to go to Canyon or on a long hike to keep from getting home sick.” Their letter ended with a petition asking to be relocated to a different CCC camp “near their own race.” [1] This complaint reflects Black workers’ deliberate assignment to Palo Duro Canyon, the “Grand Canyon of Texas,” because of its distance from nearby communities.

I encountered this letter while working on a larger project about how Palo Duro State Park became a symbol of Texas Panhandle history in the 1930s. What struck me was how easily this story—and the people behind it—had been forgotten. Palo Duro itself is a vast canyon in the Texas Panhandle visually defined by its colorful rocks and geological formations. But visitors to parks often don’t think about who built the trails, roads, and buildings that shape their experience of a landscape. Even less attention is paid to how that infrastructure tells a story—one that often excludes the full history of who lived in, used, and transformed these spaces.

Palo Duro Canyon Lighthouse. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In the 1930s, CCC leadership charged young men with building the park’s foundational infrastructure. These structures told a version of the canyon’s history centered on white settlers while erasing the presence of both Black and Indigenous peoples, respectively. Even as they shaped the park’s landscape, Black people were subjected to segregation and geographic isolation at the hands of the federal government and the Texas State Parks Board.

To place the CCC’s work in a larger historical context, I turned to ClioVis—a mind-mapping tool developed by Dr. Erika Bsumek of UT-Austin’s History Department. ClioVis allowed me to visualize how a history of Palo Duro—told through the names of places and promotional materials—has long excluded the people who helped build it.

As I charted this history of Palo Duro, it became clear how the story of Palo Duro Canyon mirrored broader patterns of West Texas history—beginning with its earliest inhabitants. Indigenous people had lived in the canyon since as early as 10,000 B.C.E. In 1541, the canyon may have been a backdrop to Spaniard Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s quest to find the fictional Quivira, one of the famed ‘seven cities of gold,’ a mythical indigenous paradise. In the mid-18th century, the Comanche (Nemene) arrived at the Panhandle Plains and “held Palo Duro Canyon as a prominent camp and trading site,” building a formidable power capable of challenging Texas expansion.[2]

In an assault on Comanche power, the United States’ army expelled them from the canyon in the 1874 Battle of Palo Duro, part of the Red River Wars. In the remainder of the decade, nuevomexicano pastores—Hispanic pastoralists who drove sheep onto the Southern Plains—continued their use of the plains. In 1876, rancher Charles Goodnight established an important cattle ranch in the depths of the canyon. The Panhandle’s ‘JA Ranch’ became a respected institution in the ranching industry.

In 1933, the CCC answered community calls to transform the canyon into a park. President Franklin Delano Roosevel created the CCC program to employ mostly young men during the Great Depression to build much of the country’s wilderness infrastructure. Young men enlisted in the program and the federal government assigned them to a CCC company, where they often lived in a future park and built roads, hiking trails, and other park facilities. Their work not only gave the public access to remote areas but also shaped how visitors experienced parks. They also influenced how people understood the history of the natural spaces through the naming of places, buildings, and landmarks.

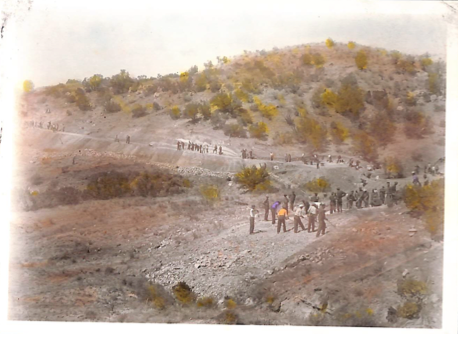

CCC boys at work. 1935. Source: Library of Congress

Soon after CCC work began, Palo Duro became the site of the largest CCC camp in the country and found itself at the center of conflict over the racial segregation of CCC workers. At its inception, the CCC camp at Palo Duro was integrated with Black and white workers. This changed in the summer of 1935 when CCC national director Robert Fechner issued a policy calling for the segregation of CCC camps. Texas State Parks Board Chairman David E. Colp, forced to select a camp to host only Black workers, said that “The Palo Duro is called ideal for negro companies owing to its location 13 miles from town.”[3] Colp hoped to avoid conflict between white communities and Black CCC workers by geographically isolating Black companies. Soon, Palo Duro State Park’s CCC camp hosted only Black workers. Consequently, they played a vital role in building the park’s infrastructure.

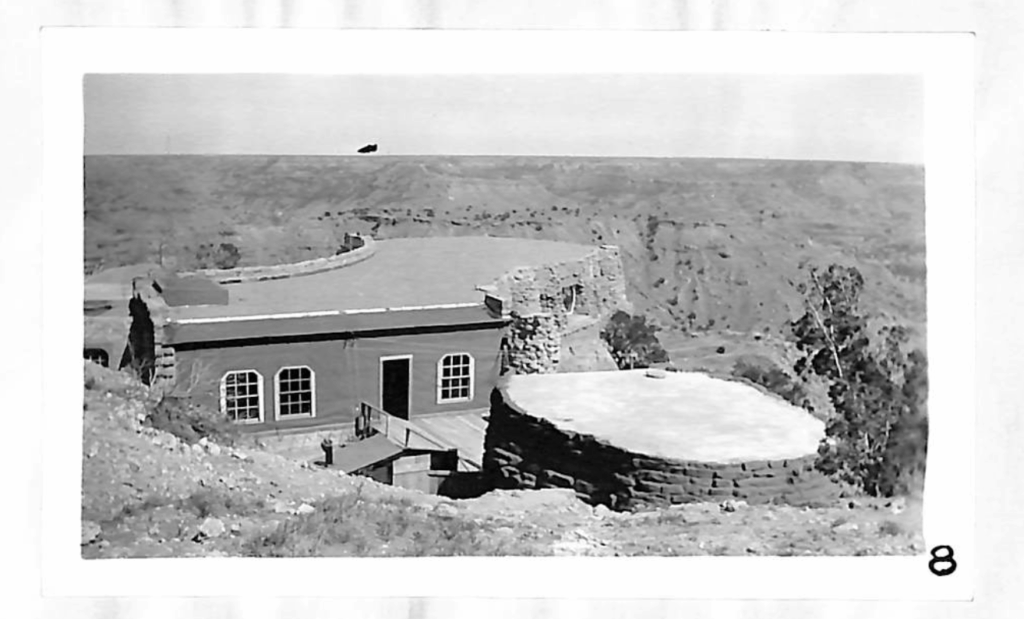

In my ClioVis project, I look specifically at how the park focused on non-indigenous men like Goodnight and Coronado to construct a frontier experience for Palo Duro tourists. Although Black workers built much of the park, CCC leadership tasked them with installing signs and creating landmarks that celebrated white pioneers. The ‘Goodnight Trail’ aimed to honor Charles Goodnight being the ‘first white pioneer to enter the canyon,’ supposedly tracing his historic entrance path. The trail also positioned Palo Duro as a place to experience history as it connected the Panhandle Plains Historical Museum (in Canyon, Texas) to the park’s entrance. Once in the park, visitors encountered ‘El Coronado Lodge,’ named to honor Conquistador Francisco de Coronado. Meanwhile, trails such as ‘Kiowa Trail’ and ‘Indian Trails’ acknowledged an Indigenous past but—in the context of promotional materials I analyzed—framed it as something distant, rather than as an integral part of the canyon’s ongoing history. Regardless, the park’s infrastructure told a story of the region that surrounded white pioneers and settlers, not indigenous people and the Black workers who built the park.

Photo of El Coronado Lodge. Untitled. Project Reports on Civilian Conservation Corps Projects in State and Local Parks, 1933-1937. National Archives and Records Administration. SP-13-16.

The power behind these names is best explained through the concept of place-making. Anthropologist Keith Basso coined the term place-making to refer to the act of assigning meaning to places. Basso argues that “…place-making is a way of constructing history itself, of inventing it, of fashioning novel versions of ‘what happened here.’”[4] He argues that through place-making, humans develop entire frameworks for understanding existence and the history around them. Therefore, the naming of places in Palo Duro State Park to honor colonizers asserted a settler-based history of the canyon itself.

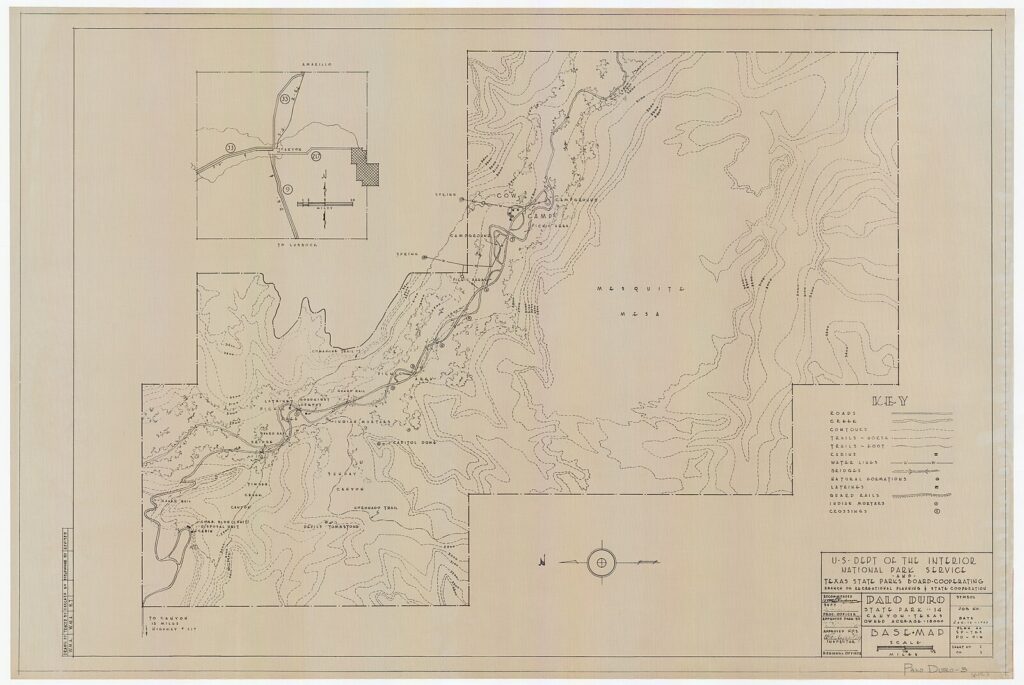

Palo Duro Canyon State Park – Base Map. 1937. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Even as Black workers built this infrastructure, they resisted the geographical isolation the state forced upon them. As noted earlier, fifteen Black workers sought President Roosevelt’s help in being relocated closer to Black communities. We “have to go to Canyon or on a long hike to keep from getting home sick,” they wrote.[5] The Black workers’ letter to Roosevelt spoke to the geographical isolation of Palo Duro Canyon, reinforced by racist policies barring them from visiting nearby Canyon, Texas and transportation challenges in reaching Amarillo, the nearest non-sundown town. At the same time, the Black workers demonstrated the ways they experienced the canyon on their own terms. As their letter said, the workers went on hikes, likely exploring distant corners of the park. The Black workers’ letter to Roosevelt encapsulated the complex nature of the Palo Duro CCC Camp.

By the summer of 1936, CCC workers’ grievances culminated in a strike. Angered by their forced geographical isolation, the workers refused to continue their labor, and a standoff ensued. They stood against an unnamed CCC commander as well as blacksmith Sid Harrison. With both sides brandishing picks and other tools as weapons, it was initially unclear if violence would erupt. The youth workers demanded better working conditions and voiced their feeling of isolation. CCC Commander Walter Caserta apparently diffused the strike after a four-hour negotiation. By the end of the summer, likely because of this confrontation, the Black companies moved to a different CCC site, and Company 894, an all-white CCC group from Bonham State Park, soon took over park construction at Palo Duro.[6]

Structure of Road from Bottom of Canyon. Palo Duro Texas. 1933-1936. Project Reports on Civilian Conservation Corps Projects in State and Local Parks, 1933-1937, Record Group 79: Records of the National Park Service. National Archives and Records Administration. SP-13-16.

Despite their role in building the park, Black people were erased from its historical narrative. Promotional materials failed to acknowledge their contributions to the park’s infrastructure, just as the CCC leaders and Texas State Parks Board reinforced this erasure through the park’s design. Beyond the park’s construction, Black pioneers like the widely revered Matthew ‘Bones’ Hooks played a vital role in the region’s history, yet their stories were similarly overlooked. Instead, the park’s infrastructure promoted a history of the white settler pioneer. Together, this structural erasure of history constitutes what historian Erika Bsumek calls ‘infrastructures of dispossession’—the ways physical and social infrastructure further alienate Indigenous—and in this instance, Black—communities from land.[7]

The consequences of this erasure are still felt today. Historian Carolyn Finney emphasizes that park infrastructure’s orientation to white audiences perpetuates disparities between white and Black people’s use of public lands. In this sense, I hope to counterweave Black workers’ history into Palo Duro’s landscape. After all, the letter from Black workers to President Roosevelt and their strike are significant events in the creation of the park. However, to make this effort truly meaningful, further work must be done to recover the voices, names, and lives of those who built the park.

In my ClioVis timeline, I expand on not only the work of Black CCC workers but also extend my argument to include the alienation of indigenous communities from the canyon’s history. ClioVis allowed me to create a network of events to visualize the connection between events in the canyon’s history and the ways the CCC brought (or didn’t bring) that history to park visitors through infrastructure.

This story of Palo Duro Canyon is not unique. People worked in segregated CCC camps in natural spaces across the United States. The park infrastructure they built often told revisionist histories about the parks. On top of this, many parks themselves were inaccessible to Black people. The State of Texas forbade Black people from entering Palo Duro until the federal government forcibly desegregated the Texas State Parks System in 1964.

Nevertheless, the infrastructure built at Palo Duro positioned the park as a particularly special symbol of Texas Panhandle history. In 1966, the community demonstrated the park’s importance to their historic mythos by inaugurating the musical TEXAS in the canyon’s basin. Producers called it “A Musical Celebration of Panhandle History.” In that sense, it becomes even more important that the history of Black CCC workers is brought to the forefront of the landscape’s narrative.

[1] Jimmie Lee Robinson and Arlena Evans, et al, Letter to Roosevelt, September 21, 1935, quoted in Jackson, “The Imprint of the Civilian Conservation Corps on Palo Duro Canyon, 1933-1937,” 148.

[2] Zapata, “Palo Duro Canyon, Its People, and Their Landscapes: Building Culture(s) and a Sense of Place Through the Environment since 1540,” 17.

[3] “CCC Companies Will Be Changed During This Week,” The Canyon News, August 15, 1935, Newspapers.com.

[4] Keith H. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 6.

[5] Robinson and Arlena Evans, Letter to Roosevelt, September 21, 1935, quoted in Jackson, 148.

[6] My knowledge of the strike at Palo Duro relies on the work of Jackson and Petersen as I was unable to access the account from Walter Caserta. Jackson, “The Imprint of the Civilian Conservation Corps on Palo Duro Canyon, 1933-1937,” 152; Petersen, “The Building of Palo Duro Canyon State Park,” 12.

Aidan Dresang is an undergraduate history major at UT-Austin. He is writing his History thesis on anti-nuclear resistance to the Comanche Peak nuclear power plant. More broadly, his research interests include North American environmental history and social movements. He currently serves as a ClioVis intern and as the History Department’s social media intern.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.