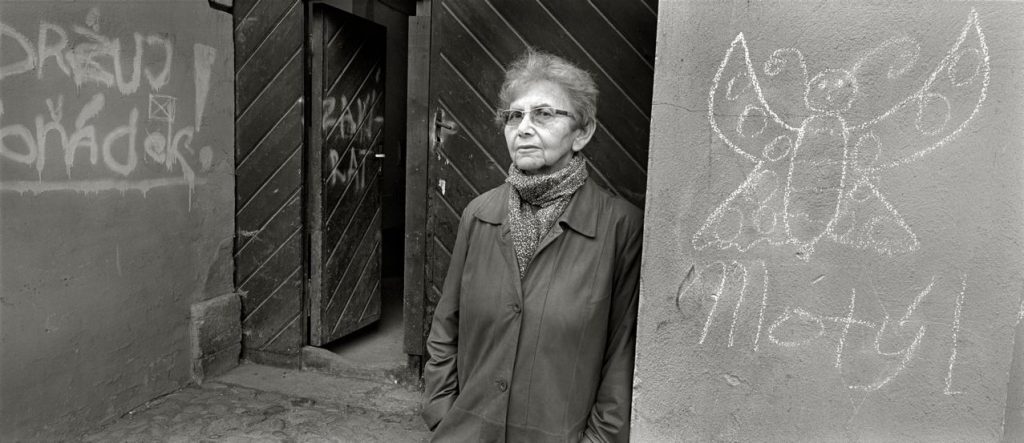

Dagmar Lieblova was a child prisoner at Terezín, deported to Auschwitz, then dispatched as slave labor to Hamburg, a city then in the daily cross-hairs of Allied bombers. There she cleared the streets of debris from the previous night’s air raids. Dagmar was finally liberated, sitting among the dead, by British troops at the notorious Bergen Belsen concentration camp. The eighty-year old Lieblova died last month in Prague, beating the odds after having been forced as a teenager to dwell four desperate years in harm’s deadly way.

The ranks of the generation that lived through the horrors of World War II are rapidly thinning. Soon, all those who have experienced the war’s seminal events will be gone. For the past five-years I have photographed the remnants of a group that endured the unprecedented terror of Nazi Germany – survivors, like Dagmar Lieblova…prisoners of Terezín.

Why am I interested in survivors of this particular concentration camp, located forty miles north of Prague, above all others?

Of the more than 40,000 detentions centers, concentration, work and death camps located throughout German occupied Europe, Terezín was unique in a number of ways, most notably because of the large number of artists and creative types imprisoned there and the legacy of art and music they produced that survived. The camp also became known, although far from the truth, as the “country club” of German camps; a reputation gained partly due to the fact that the walled prison town was skillfully staged as a “model Jewish ghetto” by the Nazi propaganda machine to successfully fool the International Red Cross inspectors into believing that all Jewish camps resembled the sham they viewed at Terezín.

Although Terezín was not an extermination camp, death was far from a stranger. Terrible conditions of depravity and evil prevailed there as well. More than 30,000 inmates perished from exposure, malnutrition and disease while awaiting transport to the East. Nearly 90,000 others were eventually deported east to Auschwitz–the vast majority murdered. Of the 155,000 Jews who were processed and held at Terezín, less than 8 percent survived the war.

The portrait of Dagmar Lieblova was taken in the doorway of the Czech Girl’s Home located on Terezín’s town square. It was here that young Czech girls, including Lieblova, were housed, more than twenty-five to each small room, after they were deemed old enough to be separated from their mothers. The chalk drawing on the building’s wall, a butterfly (motyl in Czech), has become the symbol associated with Terezín because of a poem that survived the camp and an author who didn’t. The poem I never saw another butterfly was written by Pavel Friedman, a teenager imprisoned at Terezín and later murdered at Auschwitz.

When I first started the Terezín project I was timid about approaching the survivors to ask them to talk about their experience, then sit for a portrait. I found it hard to comprehend why they would be interested in speaking to a person from rural upstate New York, raised Irish Catholic and who, at the time, really couldn’t precisely express why he was interested in making their photograph.

I was even more reluctant to ask those survivors who lived in the vicinity of Terezín to accompany me for their portrait session to the place of such personal sorrow. Much to my surprise, nearly everyone I asked made that journey of forty miles and seventy years, including Dagmar Lieblova.

I later happened upon a 2010 editorial in the New York Times that put precisely into words not only the reason for the Terezín survivors’ willingness to be a part of my project but, why I was compelled to attempt the series as well. In that editorial, the author and Holocaust survivor Samuel Pisar lamented, ‘that after 65 years, the last living survivors of the Holocaust are disappearing one by one,’ and he points out that at best, ‘only the impersonal voice of a researcher will soon be left to tell the Holocaust story’. At worst, he warns, it will be told in the “malevolent register of revisionists and falsifiers.” He cautions that this process has already begun. “This is why those of us who survived have a duty to transmit to mankind the memory of what we endured in body and soul, to tell our children that the fanaticism and violence that nearly destroyed our universe have the power to enflame theirs, too.”

Reliable sources estimate that only a few hundred Terezín inmates still survive to tell their stories. To date, I have made more than 150 portraits, in eight countries. I am honored to have been the recipient of their trust and feel fortunate to have been able to make some of the last visual records of their unique histories–The last of living memory.

This Thursday, April 12, is International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Dennis Darling has taught photojournalism, social documentary and graphic design in the School of Journalism at UT Austin since 1981. He has published two books of his work: “Desperate Pleasures” and “Chameleon With Camera.” Darling’s most recent documentary work, a photography series on Holocaust survivors entitled “Families Gone To Ash: Giving voice to the survivors of Terezin” was exhibited at the American Center of the American Embassy at Prague during June and July of 2014.