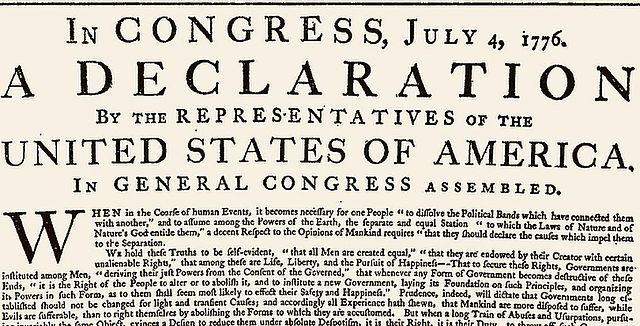

The question “how revolutionary was the American Revolution?” has long animated academic inquiry into the American experience of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Historians have often sought to answer this question by examining political and economic effects of the War of Independence. Clare Lyons’ Sex Among the Rabble suggests scholars should spend less time studying revolutionaries in statehouses and more time looking under the sheets. Her study shatters popular preconceptions that colonial sexuality emulated Georgian notions of propriety and politeness. Lyons traces both radical changes and reactionary reforms in sexual mores of Philadelphia during the decades before and after the Revolution.

Lyons’ study is not truly limited to the “rabble,” although one can understand the appeal of such a titillating title for this rousing monograph. Lyons looks at an array of sources ranging from popular print materials to court records to sordid sexual diaries compiled by voyeuristic men. Through these documents she “illuminates the interplay between sexual behavior and the cultural construction of early American understandings of sexuality” (p. 8). Furthermore, the broad temporal scope of her study shows how supple sexual behavior during the Revolution was eventually regulated along class and racial lines in the early antebellum period.

The book’s initial chapters examining discourses and sexual practices reveal a colonial society where the distribution of power between men and women was sharply contested both inside and outside of the confines of marriage. Far from depicting marital bliss, ditties in print suggested that the trope of marriage and misery has deep roots in American history. Lyons also shows how a pleasure culture that promoted promiscuity and prostitution emerged in the late 1760s and blossomed in the closing decades of the eighteenth century. This culture of casual sex suffused the entire social hierarchy of Philadelphia — although there was considerable variance in the types of liaisons sought by members of different classes.

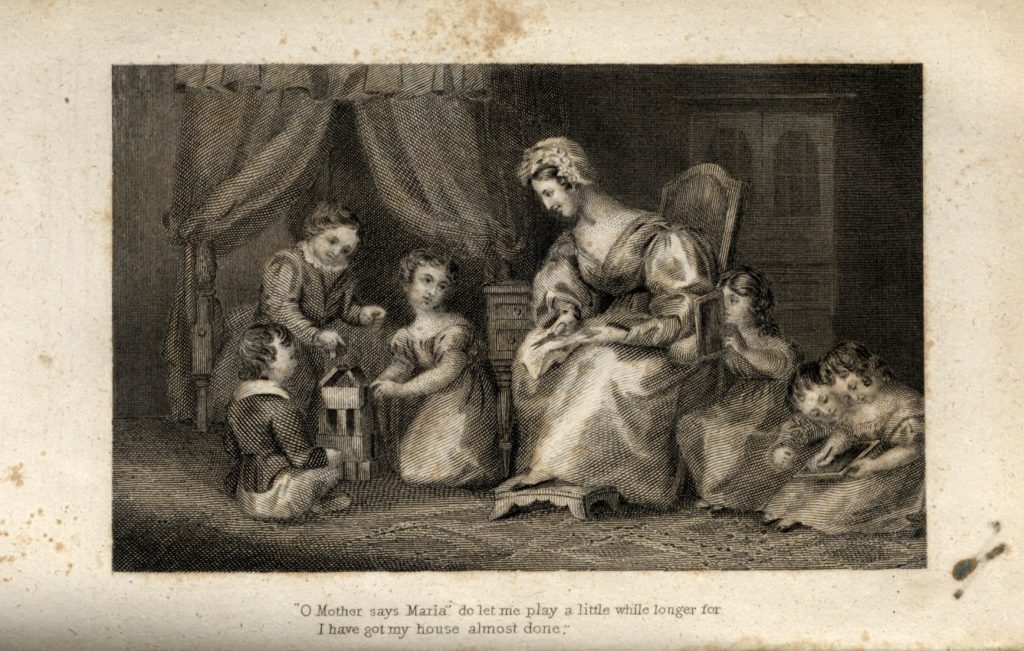

Additionally, Lyons exposes how racialized attitudes about differentiated sexual appetites and cross-racial relationships profoundly impacted this sexual culture. African Americans were characterized as a “libidinal race” by none other than Thomas Jefferson, whose own family tree was shaped by his interracial desires (p. 230). Over time, concerns about cross-racial and cross-class sexual relations drove upper classes to seek to regulate sexuality and encourage restraint instead of lustful trysts. This elite-driven sexual culture was intricately linked to notions of republican motherhood that sought to portray women as key sources of morality and virtue. If sexuality experienced a radical transformation as the colonies broke away from Great Britain this later period represented a Thermidorian reaction to these rapid changes.

Lyons’ rich source material and scintillating subject matter make this book a riveting read. This study will appeal to both historians of early America and scholars of sexuality and gender. While Lyons’ own recent experiences in political activism inspired this work, she avoids presentist judgments or imposing present-day sexual attitudes on her subjects. Instead, she carefully considers the social ramifications of a series of practices, ranging from wife-sales to enforced child support in cases of bastardy. Given the centrality of race in her account it may have helped to structure her book to more clearly delineate the racial dimensions of her findings as distinct from the class-based differences she uncovers. This small revision and perhaps culling the copious excerpts from printed poems that she includes throughout would have strengthened her study. Nonetheless, Lyons has pulled back the covers on a fascinating facet of early American society that reveals social transformations on par with the political and economic revolutions debated by other scholars of this time period.

Jon Buchleiter is a third-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He studies United States history with particular interest in US foreign policy of the Cold War. His current research examines the institutionalization of arms control and disarmament efforts and successive administrations approached and prioritized arms control initiatives. At UT, Jon is a Graduate Fellow with the Clements Center for National Security and Brumley Fellow with the Strauss Center for International Security and Law. Jon received his BA in Peace, War, and Defense and Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.