Can historians reinterpret the American Civil War as a global event? This question inspired Henry Wiencek, a first year doctoral student in history at the University of Texas at Austin, to create the website “The Civil World: A Global ‘War Between States.’”

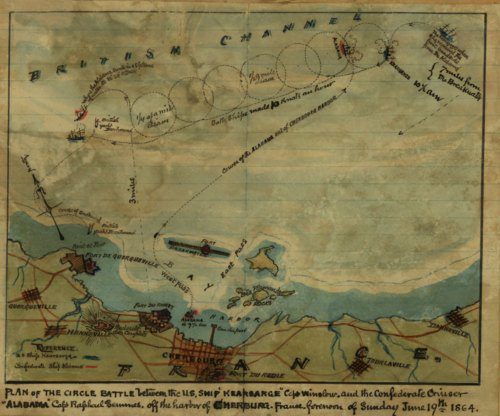

A rendering of the naval battle between in the infamous CSS raider, Alabama, and the Union Keasarge.

A rendering of the naval battle between in the infamous CSS raider, Alabama, and the Union Keasarge.

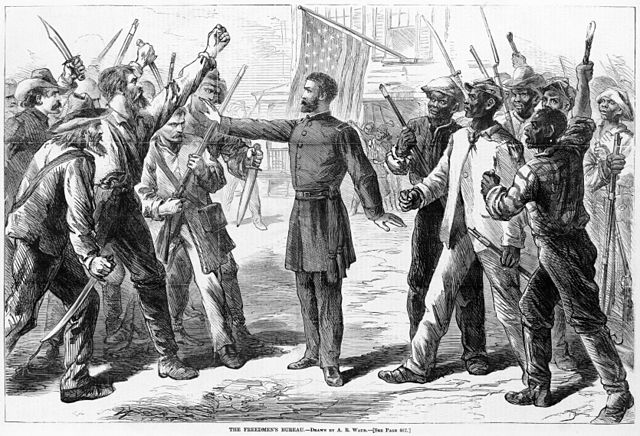

Weincek designed the site to provide an “intellectual portal” for historians, students, and general interest readers alike to consult in order to learn about the economic, diplomatic, and social changes ushered in by the Civil War on the international stage. That the Civil War can be interpreted as an international event may come as a surprise to many readers. The conflict, after all, is often taught and thought of as a regional phenomenon: its origins, key players, events, and consequences are traditionally thought to be constrained within U.S. borders. Wiencek’s website tells a different story. Through its diverse collection of maps, newspaper clippings, and recent historical literature, “A Civil World” argues convincingly that the war’s international stage played a significant role in the war’s origins, trajectory, and eventual outcome.

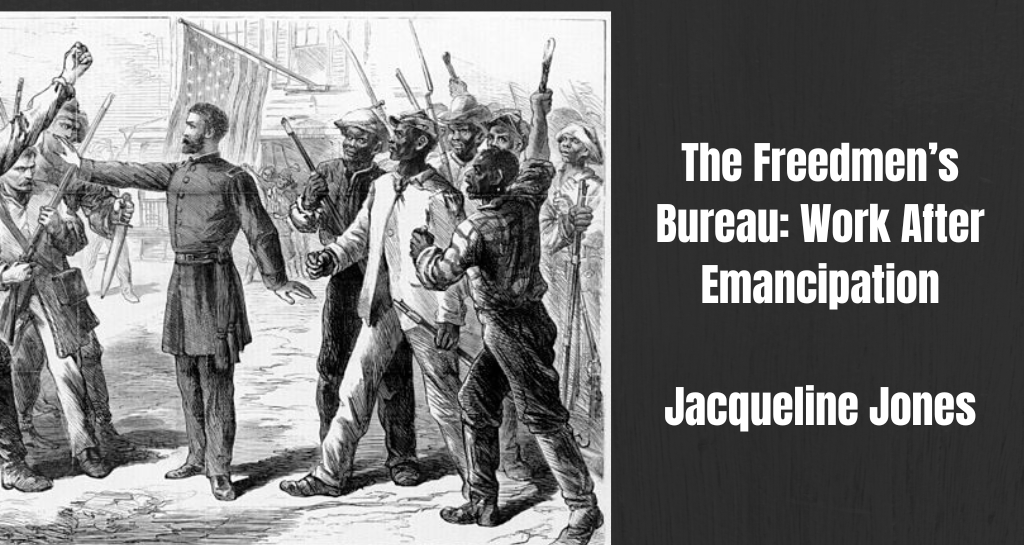

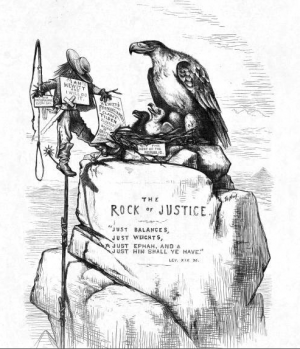

(A Harper’s Weekly cartoon satirized the widespread fear that a post-bellum, pre-Reconstruction America will descend into a “Mexican” state of constant civil war.)

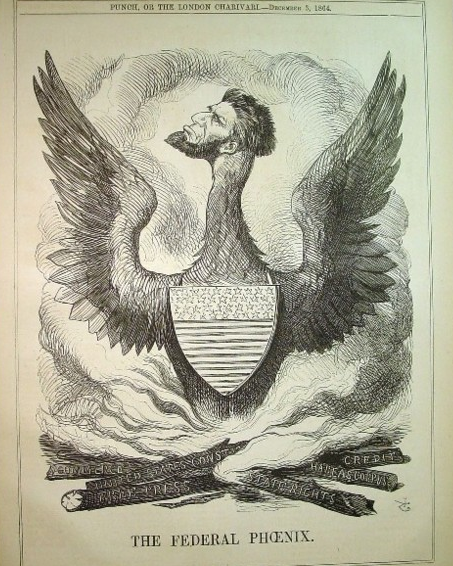

Abraham Lincoln as the “Federal Phoenix” in the British magazine Punch.

University of Texas at Austin – Department of History

(Professor: Jeremi Suri)