by Ashley Nelcy García, Department of Spanish and Portuguese

An earlier version of this review was published on halperta.com.

What is a digital archive? I asked myself this question in the weeks before submitting this review. While digital archives are typically defined as a coherent set of digital objects that have been put online by a library or an official archival institution, Más de 72 challenges the notion of what we can identify as a digital collection of records.

Screenshot of Más de 72

Más de 72 is a digital project that collects primary sources pertaining to the massacre of 72 migrants from Central and South America and India. The documents and media shared on this site shed some light on the mass murder that occurred in San Fernando, Tamaulipas, Mexico in 2010, under the administration of Felipe Calderón. The collection was created by Periodistas de a Pie, an organization of active journalists that seeks to raise the quality of journalism in Mexico. The International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), CONNECTAS, and journalists who were invited to participate in the project supported the development and completion of this project.

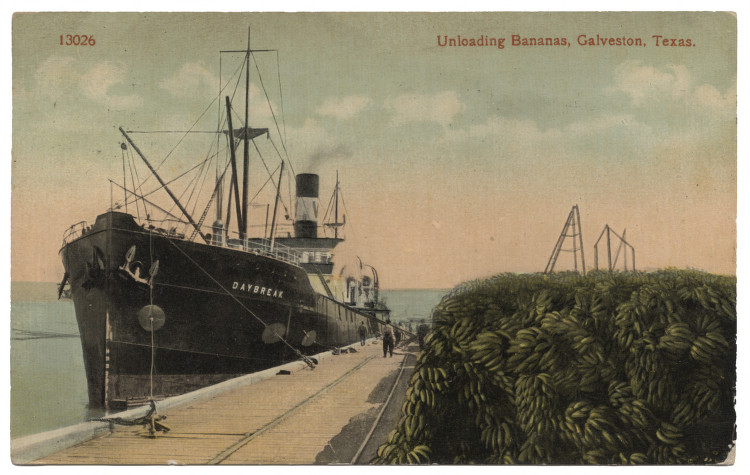

The collection is a valuable resource for individuals interested in Mexico’s recent history, memory, and human rights issues. Visitors can access primary sources such as official documents from Mexico and the United States, including some judicial records and declassified files. Testimonies from surviving family members recorded in video and audio by journalists, as well as photographs and maps are also available. Additionally, journalistic investigations and reports published by human rights entities provide context to users unfamiliar with the case.

via Más de 72

Más de 72’s primary strength is its presentation. The site contains six different tabs or capítulos (chapters) that provide different types of information. For instance, the sections titled “La Masacre” (The Massacre) and “Después de la Masacre” (After the Massacre) include official and visual documents associated the mass murder of the 72 migrants. Under these tabs, visitors can access documents like the press release from the Secretaría de Marina (Secretary of Marine) and the diplomatic cable that the U.S. Embassy sent to the Department of State. Online browsers with an interest in the role of official documents can also download more than 50 files under the tab titled “Transparencia” (Transparency). On the other hand, users interested in criminal records and procedures and migration studies can access a list of objects found in the location where the massacre occurred and the names of the victims under “Después de la Masacre.” In regard to organization, it is important to note that the names of the victims are listed under their country of citizenship and under the month and the year they were identified.

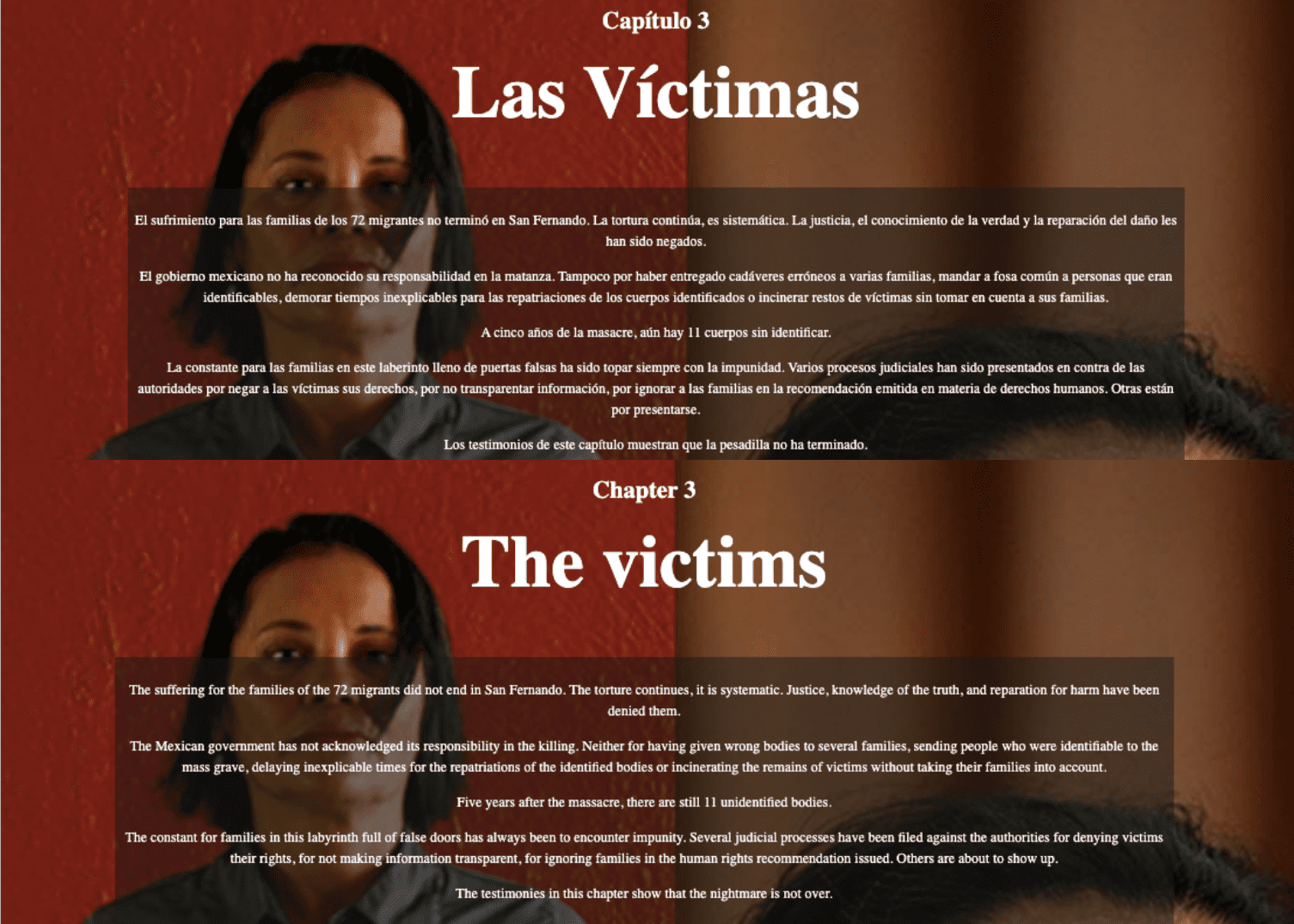

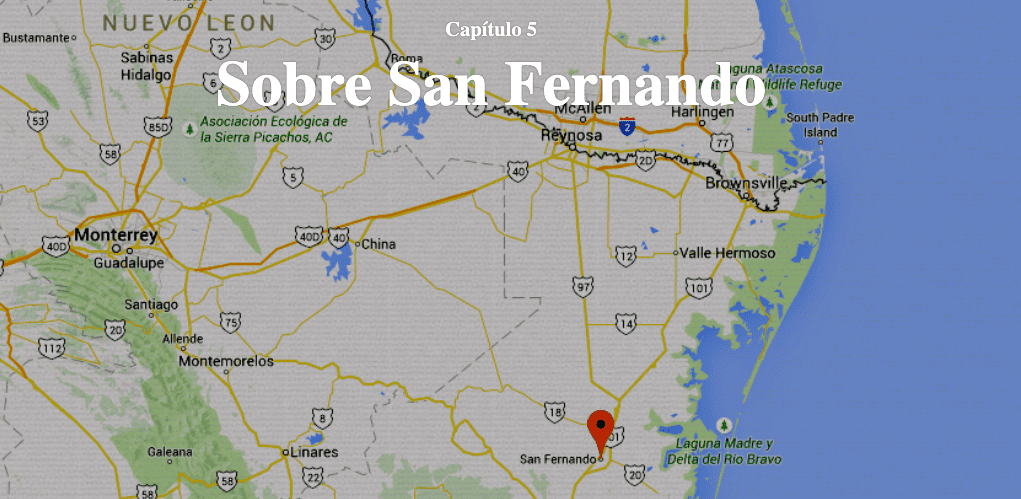

On the other hand, the tabs titled “Las Víctimas” (The Victims), “Los Culpables” (The Culprits), and “Sobre San Fernando” (About San Fernando) provide more detailed information regarding people and location. These sections can benefit visitors interested in oral history, memory, gender studies, and digital cartography. Under “Las Víctmas”, users can listen to four testimonies provided by victims’ surviving family members. “Los Culpables” has a list of the men and women involved in the mass murder; this section includes the names, the photos, the list of crimes they committed, and external links that provide additional information. The section titled “San Fernando” includes a digital map from Time Mapper that helps users identify the mass graves and the people that have been disappeared in Tamaulipas by geographic location.

Overall, the site benefits users who cannot visit Mexico or Tamaulipas. Aside from scholars, people who can potentially benefit from this repository include but are not limited to: family members of migrants and people who have been disappeared, residents from the state of Tamaulipas, people with relatives in the northern part of the Mexico, journalists, lawyers, and activists. Although the project is not affiliated with libraries, governmental, or academic institutions, Periodistas de Pie is open to working with community members. As stated in “Creditos” (Credits), users can share documents or materials by sending an email to the listed email address. In addition, the organization invites visitors to collaborate–either with skills or donations–to continue developing the site.

The website has some technical problems. It would be difficult for someone who is unable to read Spanish to understand the majority of the information included on the platform. Additionally, some links, hyperlinks, and images need to be updated. More descriptive metadata would also benefit the project and there is a need to assist with the second part of the collection titled, “Segunda Entrega: Fosas de San Fernando” (Second Delivery: San Fernando’s graves). While these are minor setbacks, they also provide an opportunity for archivists, scholars, and web developers to get involved with the project.

Capítulo 5: Sobre San Fernando (Chapter 5: About San Fernando) via Más de 72

Even though Más de 72 is not described as a “digital archive” by the journalists at Periodistas de Pie, this platform serves as a repository of digitized primary documents associated with an historical event. In this regard, it is important to consider how the digital humanities field can be co-opted by elites to control historically politicized spaces. We need to be thinking about what is at stake when the term “archive” is used to control information. The politics of archiving is especially important where journalists–the authors of many of the documents in Mas de 72–find themselves in a violent climate and are rarely protected by institutions of power.

![]()

Read More:

Más de 72

![]()

You Might Also Like:

Authorship and Advocacy: The Native American Petitions Dataverse

Rising From the Ashes: The Oklahoma Eagle and its Long Road to Preservation

Digital Learning: Starting from Scratch

![]()