In late 1546, auditor-president Pedro de la Gasca landed in the New World charged with retaking the entire continent for the crown, from Nicaragua to Chile. After having beheaded the viceroy, Gonzalo Pizarro had declared himself ruler of larger Peru with a fleet controlling the South Sea, from Callao to Panama. Curiously, La Gasca came with no armies, just a pile of blank decrees signed by Charles V. In one year, however, La Gasca quickly took over Pizarro’s fleet and routed Gonzalo into the Peruvian heartland. He was able to accomplish this because of the power of royal decrees and edicts granting rewards to any potential turncoat. La Gasca quickly dispatched the Pizarros, reorganized Peru, and promptly went back to become bishop of Palencia in 1550.

This largely bloodless, swift conquest of conquistadors by paperwork seems not to have caught the attention of historians of the sixteenth-century Spanish Indies, who were accustomed to narrating gory blood baths in Tenochtitlan. How did a faraway monarch manage to control a sprawling empire teeming with violent and ruthless factions, including, not only raiding conquistador-pirates but also thousands of theocratic friars and rebellious indigenous lords, all willing and able to seize control. This is the subject of Adrian Master’s extraordinary We, the King which was published by Cambridge University Press in 2023.

Anyone superficially familiar with the history of conquest and colonialism in the Americas knows two things: First, Spain imposed a ruthless autocratic regime via top-down religious bureaucracies that enforced religious compliance and cultural uniformity. Second, Anglo America was a decentralized society of settlers with loose crown oversight until the eighteenth century, when overreach triggered revolution. This is not a cartoon version of history but rather our current historiographical canon. It is the argument at the heart of John Elliott’s monumental Empires of the Atlantic (2006). The Anglo-American bottom-up and Spanish American top-down dichotomy also structures the writings of the entire Cambridge School, from J.G.A Pocock to Quentin Skinner to David Armitage. Clerical Dominican and Jesuit theology allegedly organized top-down state formation in the south whereas bottom-up markets and indirect providence did it in the north.

In a bold, deeply researched book drawing on no less than twenty-six archives, Masters shatters this paradigm. The liberal and decolonial obsession with top-down Spanish autocracy has overlooked that the discourse of tyranny, underlying all neo scholastic theories of regicide, implied vast bottom-up forms of communication between vassals and monarchs. To claim legitimacy, that is not to be a tyrant, the crown encouraged all sorts of bottom-up paperwork communication via petitioning, audits, and denunciation (which was the point of the Inquisition). In the Spanish Indies, the state was created from the bottom up every bit as much as it was in Anglo America.

Masters’ subject is the hundreds of thousands of royal decrees created in the sixteenth century, but he does not discuss the millions of viceroyal edicts, mandamientos. Scholars have argued that the crown regulated everything from the length of trousers of Purepecha commoners to the number of horses of Nahua lords. We have been told that the crown rounded up natives into towns and issued top-down decrees on how to sleep on mattresses. The topic of race is especially dear to this scholarship. The crown decreed out of thin air prefigured categories of human difference. From the top-down, it engineered republics of Indians, Spaniards, Mestizos, and some forty Casta out of the Reconquista experience with purity of blood statutes.

Masters has no patience with any of this. Most decrees, he shows with brilliant empirical skill, came from bottom-up petitioning from millions of vassals, including both enslaved people and women. Even the very language of the decrees was often taken verbatim from bottom-up petitioning. The function of the Council of Indies was primarily to handle bottom-up paperwork on unsolicited reform and legislation. To be sure, this was no democracy where commoners had unmediated access to the Council and paperwork, but neither, it should be said, is ours. Be that as it may, Masters shows that systems of legislating petitioning were largely responsible for the creation of most racial categories in the Indies. Indigenous factionalism prompted petitions to draw casta (caste) and mestizo distinctions. Every bit as much as friars, bishops, and viceroys, native commoners participated in the creation of colonial categories of human difference.

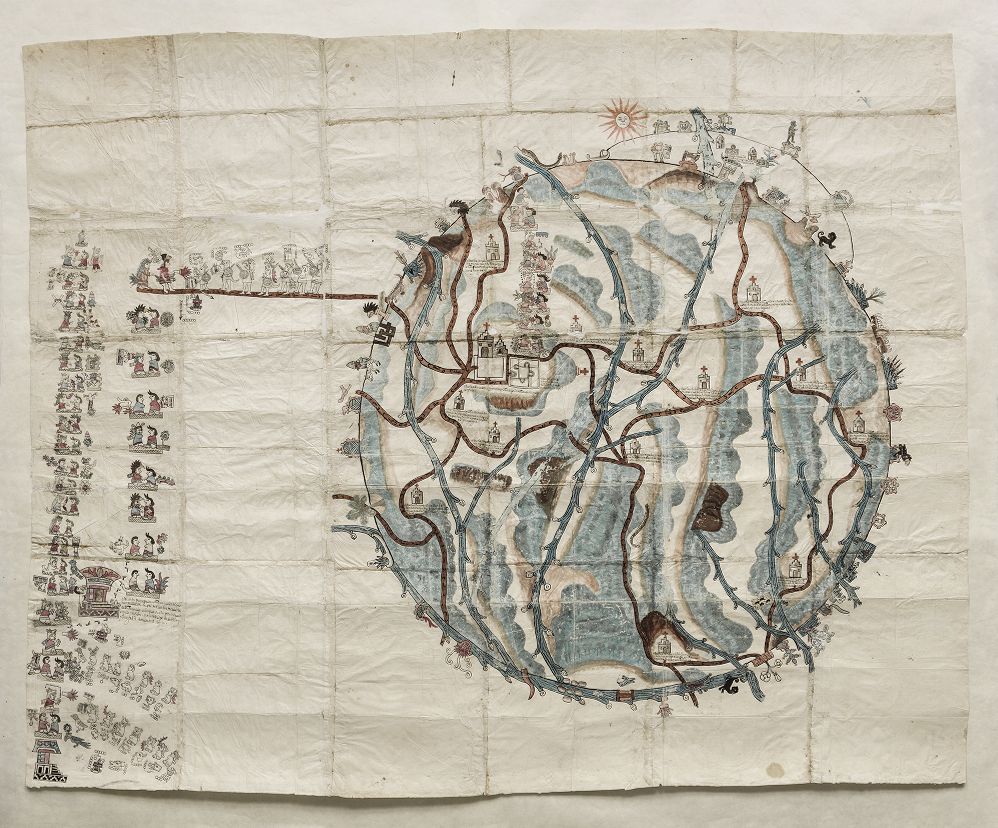

This is not a minor contribution. The scholarship on colonial Latin America is plagued by teleological narratives. As with any bad script, we all know how the movie ends. Categories, institutions, allegedly all came down prefigured from Spain. Masters shows throughout that the labor of making of the law not only took up a lot of actants (scribes, paper, ink, tlacuilos, ships, rowers, servants, porters, muleteers, magistrates, rivers, oceans, candles, seals, chasquis) but also rendered the system unpredictable. It took individual and communal agency to succeed. It also involved, stubbornness, networking, resilience, corruption, lying, luck.

Along with the top-down authoritarian shibboleths, the literature on the Spanish Empire is packed full of picaros, the much-needed Macondo picaresque in our much-loved liberal and decolonial narratives. Masters is aware that the Indies was not Spain and that petitioning in the Indies changed over time. Corruption and deception were the twin bête-noir of legislation (decrees, edicts, ordinances).

Masters shows that over the entire century the crown struggled to stem corruption and misinformation from undermining its own legitimacy before vassals. In fact, this was the main function of Council magistrates. In a series of riveting chapters, Masters shows how various council audits transformed Indies systems of communication, relegating elite women from legislative decisions, for the wives and daughters of magistrates were the main conduits used by petitioners to communicate and sway the will of magistrates. Masters also shows that the battle to control misinformation led to the creation of a far less passive crown toward the end of the century, capable through its own archives of finally assessing the credibility of Indies testimonies accurately. For every picaro there was an archive.

This book is a tour de force that ought to transform our understanding of Latin American colonial state formation. We, the King: Creating Royal Legislation in the Sixteenth-Century Spanish New World is a brilliant study that I recommend to all.

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra is the Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History at the University of Texas.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.