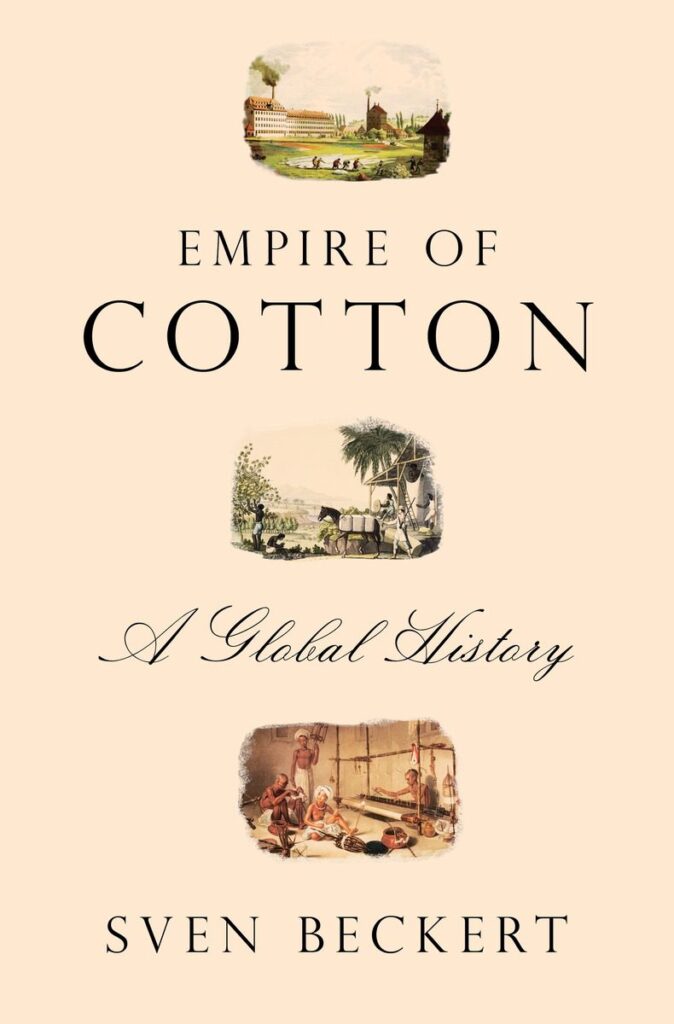

Sven Beckert places cotton at the center of his colossal history of modern capitalism, arguing that the growth of the industry was the “launching pad for the broader Industrial Revolution.” Beckert follows cotton through a staggering spatial and chronological scope. Spanning five thousand years of cotton’s history, with a particular focus on the seventeenth to twentieth centuries, Empire of Cotton is a tale of the spread of industrialization and the rise of modern global capitalism. Through emphasizing the international nature of the cotton industry, Beckert exemplifies how history of the commodity and global history are ideally suited to each other. Produced over the course of ten years and with a transnational breadth of archive material, Empire of Cotton is a bold, ambitious work that confronts challenges that many historians could only dream of attempting. The result is a popular history that is largely successful in attaining the desirable combination of being both rigorous and entertaining.

Beckert frames his history of cotton with two intertwining terms: “war capitalism” and “industrial capitalism.” Both terms lack precise definitions but Beckert generally refers to their underlying themes. A play on the term “war communism” from the Russian Civil War, “war capitalism” was a period when European statesmen and capitalists established their dominance in global cotton networks, often through violent, imperialist means of conquest and expansion. Beckert counters the notion that Europeans controlled the cotton industry as a result of scientific innovation, arguing that, “Europeans became important to the worlds of cotton not because of new inventions or superior technologies, but because of their ability to reshape and then dominate global cotton networks.” “Industrial capitalism” evokes the more discreet ways in which states intervened to protect the interests of global capitalists through more diplomatic channels, preserving the initial gains made through “war capitalism.” Neither concept is exclusive, with “war capitalism” and “industrial capitalism” continually interacting with one another and overlapping chronologically, as Beckert underscores how “industrial capitalism’s institutional innovations facilitated war capitalism’s death.”

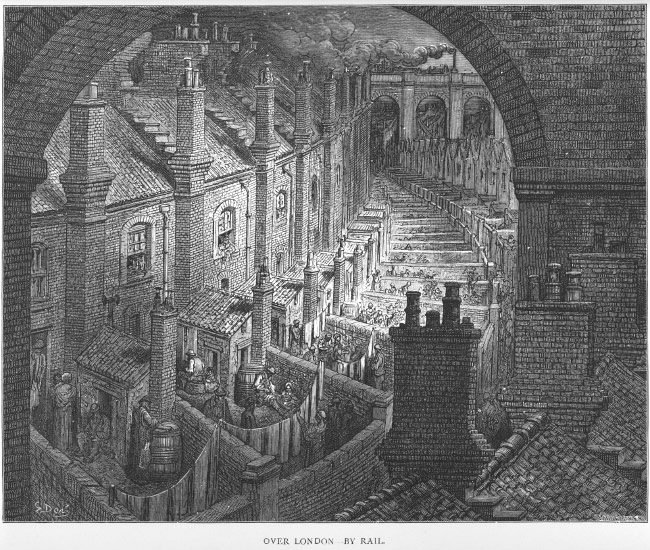

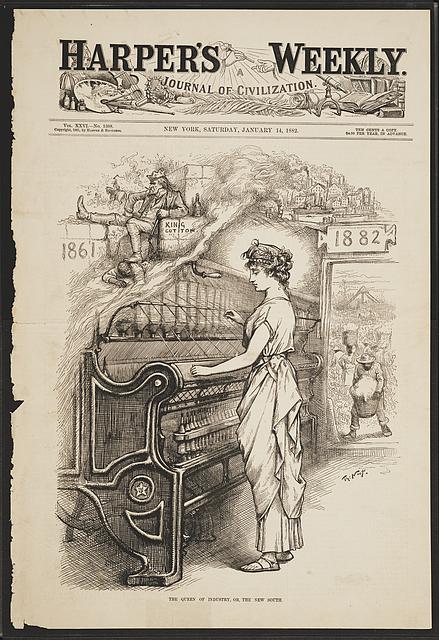

Through the discussion of these two concepts, Beckert underlines the importance of forced labor, with an emphasis on slavery in particular, in the development of global capitalism. Beckert claims that “the flow of cotton from the United States to Europe and of capital in the opposite direction” was at the core of developing international trade networks. The author echoes an important and emerging argument: modern global capitalism relied upon the growth of the cotton industry, which was itself indebted to slavery, as “cotton demanded quite literally a hunt for labor.” Beckert asserts that the “physical and psychological violence of holding millions in bondage were of central importance to the expansion of cotton production in the United States and of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain.” Empire of Cotton subsequently reads as a critique of long held complacencies about the centrality of the slave trade to the development of modern capitalism.

Beckert establishes a wide-ranging, holistic study that glides from country to country, focusing on the market of cotton rather than diving into the weeds of national specificities. One of the great strengths of macrohistory is that these works tend not to be restricted by the confines of the nation state, providing a means of escaping exceptionalism and promoting a more global approach to historical study. Expanding on such works as Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History and more recently Elizabeth Abbott’s Sugar: A Bittersweet History Beckert outlines a vast narrative told through the lens of a singular commodity. With regard to the history of cotton specifically, Beckert largely complements Giorgio Riello’s 2013 book Cotton: The Fabric That Made the Modern World, which traces cotton production from 1000-2000. While there is common ground between the two authors in terms of scope and a focus on the economics of the cotton industry, Beckert emphasizes the direct link between the cotton industry and the tumultuous development of modern capitalism, whereas Riello is more interested in the processes of globalization.

For all its impressive qualities, however, there are certain shortcomings that should be addressed. There is a lack of conceptual engagement with violence, modern capitalism, and the Industrial Revolution, each of which merit further attention. Moreover, “war capitalism” and “industrial capitalism” are rather elusive analytical frameworks, making it difficult to directly discern between the two and their distinct utility. Additionally, the unquestioned preeminence of cotton presents an overly monocausal explanation for larger trends that are arguably more multifaceted. For instance, E.A. Wrigley (2010) argues that in 1801 the British Empire’s four largest industries were cotton, wool, building, and leather – with each component being of roughly equal size. Therefore, the assumption that cotton has a direct connection to industrialization prior to 1801, and is the most important of the four largest industries, warrants more of a discussion. Furthermore, there is a curious evasion, considering Beckert’s revisionist stance, of one of the most unavoidable scholarly traditions surrounding modern global capitalism: Marxism. Perhaps this is partially due to the enormity inherent in such a study. Nevertheless, cotton’s centrality is taken as a given, and while it would be perfectly legitimate to argue that the cotton industry was vital to the Industrial Revolution, Empire of Cotton’s analytical base would be on much firmer ground with a deeper conceptual engagement with violence and capitalism.

On the other hand, it could also be argued that Beckert is merely being conscious of his readership and aiming to make academic scholarship more accessible to a wider audience. What is lost through a certain amount of oversight in analyzing conceptual frameworks is counterbalanced by its engaging narrative. Empire of Cotton is more than deserving of its wide acclaim, demonstrating the potential of ambitious and exciting trends in historiographical inquiry. The author strikes a fine balance between effortlessly fluent prose and complex subject matter, making a significant contribution to the fields of global history and history of the commodity as well as enticing a wider audience. While Empire of Cotton is a dense, impressively researched book, Beckert manages to appeal to a broader audience and create a fluently written, academically rigorous account of cotton’s journey from a local, artisanal product to a global, mass-produced commodity.

You may also like:

Review: Seeds of Empire by Andrew Torget (2015)

H.W. Brands on the rise of American capitalism

Review: The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective by Robert C. Allen (2009)