When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

–Leviticus 19:33-34 (New JPS Translation)

One rainy April morning in 2011, I requested Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an from the Rare Book Room in the Library of Congress. Outside, tulips blazed in bright patches of red around the Capitol building. The flowers reminded me of their origins in the Ottoman Empire. The sultan had first sent them as diplomatic gifts to European rulers in the sixteenth century, and by the mid-seventeenth, the trade in the bulbs of these plants had reached a frenzied pitch in the Netherlands.[1] Jefferson would add them to his garden at Monticello in 1806.[2] And so it was that, through contact with Muslims long ago, this stunning flower had eventually reached North America, where it now reigns as a sign of spring.

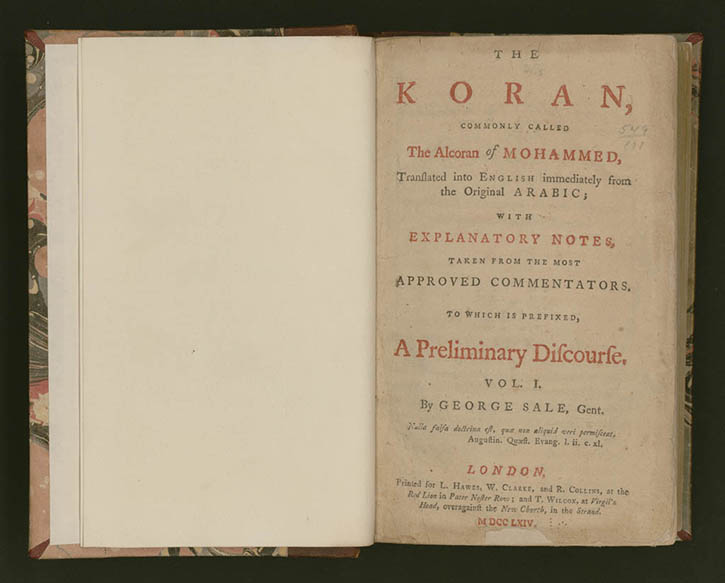

Summoned with nothing more than the requisite library card and the relevant call number, the two volumes of Jefferson’s Qur’an arrived unceremoniously at my desk in less than ten minutes. I sat amazed. A national treasure was mine to peruse. As a historian and a citizen, I’d thought for years about what Jefferson’s Qur’an might have meant. Now, suddenly, I could touch the brown leather bindings, and hear the slight crackle of the yellowing pages as I turned them. The volumes were far too delicate, I thought, to be touched by anyone. I could not help but recall that eight months earlier in Florida an addled pastor of a nearly nonexistent congregation had held a press conference promising to burn multiple Qur’ans in protest against a proposed mosque in New York City. (He had made his threat good days before in March 2011, with disastrous consequences in Afghanistan.)[3] The Florida minister believed he was exercising his First Amendment right to express how execrable he thought Islam was. Inadvertently, he revealed how little he knew about the historical importance of the Qur’an to Protestants in both Europe and America. For them, it had been more common since the seventeenth century to translate the sacred text for Christian readers than to consign it to the flames.

For me, the pages of Jefferson’s Qur’an represented sacred historical evidence, not of the truth of Islam, but of the capacity and eagerness of some early Americans to learn about that faith. As a professor of Islamic history, I wanted to know what early Americans knew about Islam and how they’d learned about the religion and its history. To my surprise, I found that many Americans in the founding era, despite the tenacious legacy of misinformation from Europe, refused to yield to contemporary fears promoting the persecution of Muslims. They preferred to be heirs to a less prominent but important strain of European tolerance toward Muslims, one whose influence had thus far been over looked in early American history.

Jefferson’s two-volume English translation of the Qur’an had grabbed the national spotlight in January 2007, when Keith Ellison, the country’s first Muslim congressman, chose to swear his private oath of office on the Founder’s sacred text. At the time, I thought that the outrage expressed by some toward Congressman Ellison’s election and private swearing-in on the Qur’an might have been averted if only more Americans had known their own founding history better, a past that had prepared an eventual place for Congressman Ellison, not in spite of his religion, but because of it.

The idea of the Muslim as citizen and federal office holder is not new to the United States. It was first considered in the eighteenth century. Yet today some claim that even the concept of a Muslims citizen in elected office is threatening to the nation’s identity. I argue the opposite in this book: The concept of the American Muslim as citizen is quintessentially evocative of our national ideals. Indeed, the inclusion of Muslims as future citizens in early national political debates demonstrates a decided resistance to the idea of what some would still imagine America to be: a Christian nation.

. . . As Americans, the vast majority of us might recall that our ancestors began here as outsiders, immigrants and strangers, not citizens; an even more compelling reason to remember the Golden Rule. Jefferson would do so at the end of his life, following a pronounced pattern in those who had fought before him against the persecution of Muslims.

Denise A. Spellberg, Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders

Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an reviewed on The Daily Beast

Adapted from the Preface to Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders

Copyright © 2013 by Denise A. Spellberg. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

[1] For the early Ottoman and European trade in this luxury, which actually began in the sixteenth century, see Ariel Salzmann, “The Age of Tulips: Confluence and Conflict in Early Modern Consumer Culture (1550-1730),” in Consumption Studies and the History of the Ottoman Empire, 1550-1922, ed. Donald Quataert (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000), 84, 87, 89; Mike Dash, Tulipomania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused (New York: Crown, 1999), 34, 224. Although tulips were propagated in England as early as 1582 and may have crossed into their North American colonies in the seventeenth century, the flowers also became transatlantic at the same time with the arrival of the Pennsylvania Dutch, who counted the three petals of the tulip as symbols of the Trinity. The Ottomans also imbued the tulip with powerful but very different Islamic religious symbolism.

[2] Edwin M. Betts and Hazelhurst Bolton Perkins, Thomas Jefferson’s Flower Garden at Monticello, revised by Peter J. Hatch, 3rd ed. (Monticello, VA: Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 2000), 25-26.

[3] Damien Cave and Anne Barnard, “Minister Wavers on Plans to Burn Koran,” New York Times, September 9, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/10/us/10obama.html?pagewanted=all; Enayat Najafizada and Rod Nordland, “Afghans Avenge Florida Koran Burning, Killing 12,” New York Times, April 1, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/02/world/asia/02afghanistan.html?…all. It is worth noting that the Southern Poverty Law Center has designated the minister Terry Jones and his Dove World Outreach Center based in Florida as an anti-Muslim hate group; see Robert Steinback, “The Anti-Muslim Inner Circle,” Intelligence Report, no. 142 (Summer 2011), Southern Poverty Law Center.

Photo of tulips at Monticello: Bandanamom, Flickr, used with permission

Many previous studies breezily pit “Islam” against the “West.” Sidestepping the assumption that the two categories are essentially different, GhaneaBassiri studies the actual lived tradition of Muslims in America instead of second-guessing their compatibility.

Many previous studies breezily pit “Islam” against the “West.” Sidestepping the assumption that the two categories are essentially different, GhaneaBassiri studies the actual lived tradition of Muslims in America instead of second-guessing their compatibility.