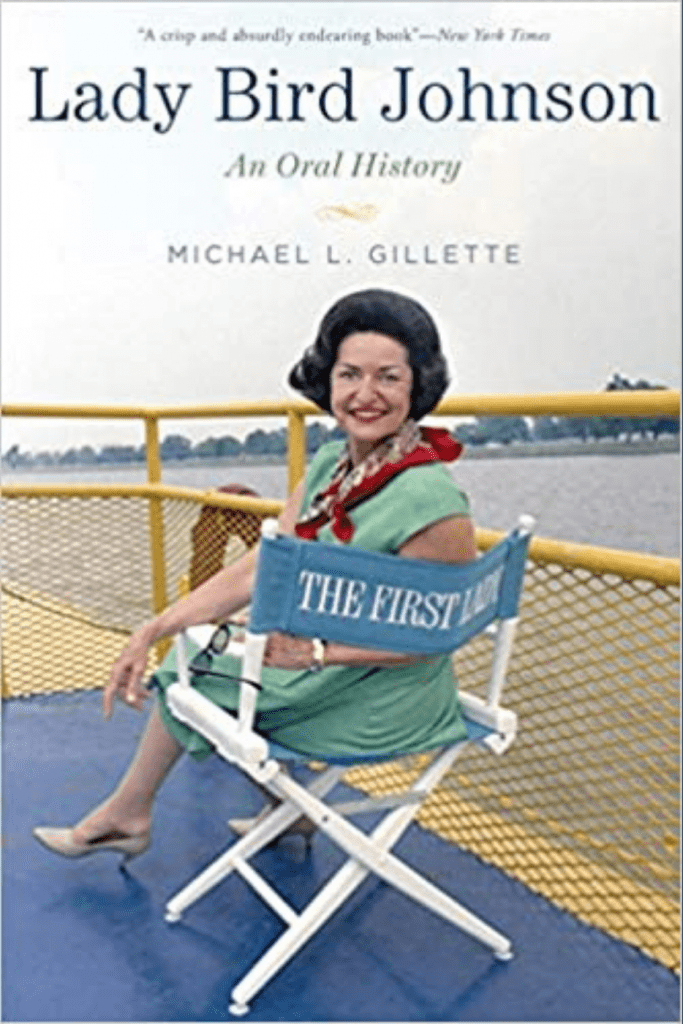

By Michael Gillette

I had already conducted the first five oral history interviews with Lady Bird Johnson when she telephoned my LBJ Library office one day in the spring of 1978. Her first words were “Hello, Mike. How would you like to do something zany?” Before I could speculate what she could possibly mean by “zany,” she explained: “Would you like to accompany me to my fiftieth high school reunion in Marshall, Texas?” I eagerly accepted the invitation.

The trip was an extraordinary adventure in time travel that added rich context to her oral history narrative. The reunion with old Marshall High School friends brought out her youthful spirit and warmth. As she addressed the gathering, I thought of her graduation fifty years earlier when her shyness was so excruciating that she was relieved to learn that her class ranking—the third highest–spared her from having to give a speech. But now, as the former first lady delivered an eloquent, humorous, nostalgia-filled speech, she spoke effortlessly.

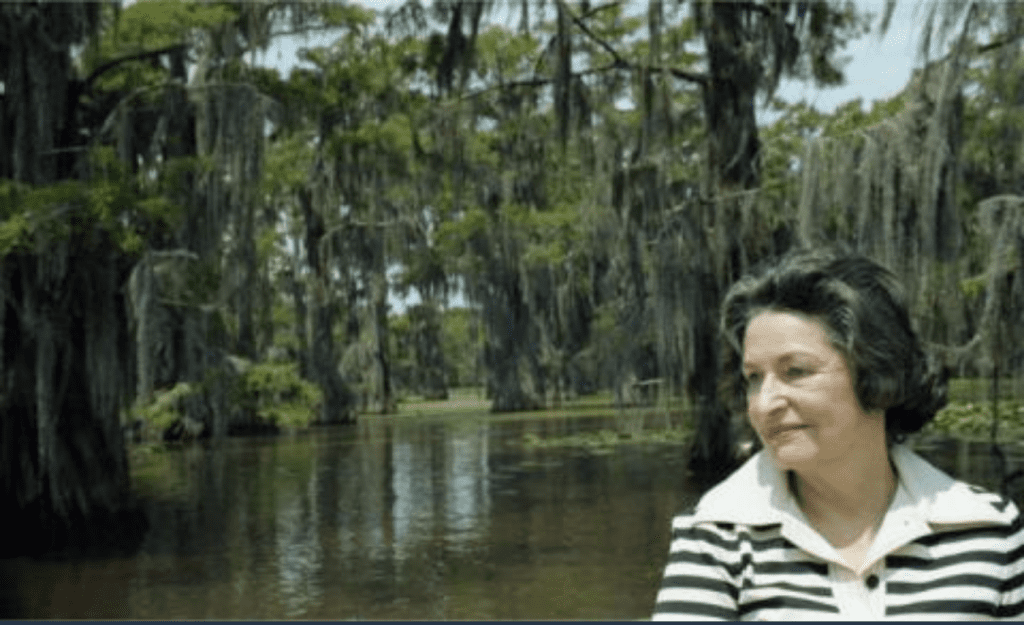

The East Texas trip took us to several landmarks of her youth. We walked around the stately antebellum Brick House, where she was born. We stopped at the beautiful, lonely country Scottsville cemetery where her mother was buried when Lady Bird was five years old. We climbed into jon boats and ventured onto Caddo Lake amid the haunting majestic Cypress trees, laden with Spanish moss. I could readily see how she had developed her love of nature in such a spectacular setting.

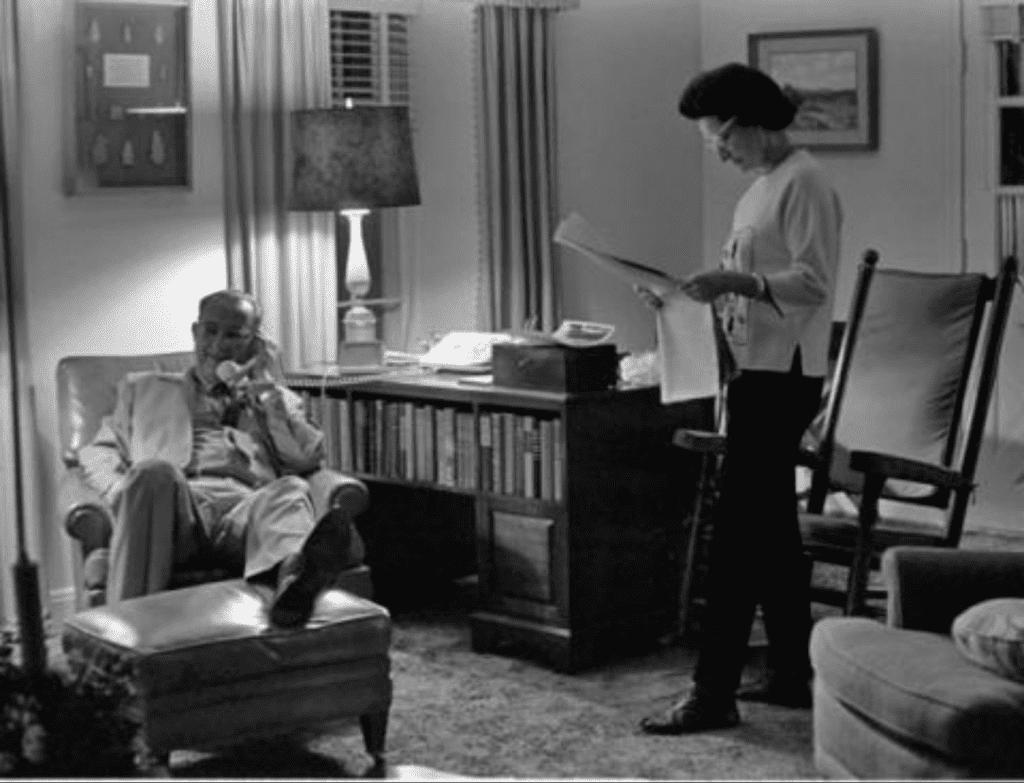

In August 1977, almost a year before our trip, I had begun the series of oral history interviews with Mrs. Johnson that would ultimately comprise forty-seven sessions. Our interviews usually took place on weekends at the LBJ Ranch, where interruptions were minimal. My oral history staff and I would prepare a chronological outline for each year, along with a thick file of back-up correspondence, appointment calendar entries, and press clippings. Mrs. Johnson would review the entire folder of material to refresh her memory and make notes before we began recording each interview. Over a span of fourteen years, I conducted the first thirty-seven interviews. After my transfer to the National Archives in Washington in 1991, Harry Middleton, the LBJ Library director, continued the interviews.

In 2011, two decades after my departure from the LBJ Library staff, I learned that the library was preparing to release Mrs. Johnson’s long-sealed interviews in May of that year. I immediately prepared a book proposal to Oxford University Press, which had recently published a new edition of my Launching the War on Poverty An: Oral History. Once Oxford approved the project, my task was to edit her 470,000 words into a manuscript of less than half that length in time to publish it before Mrs. Johnson’s centennial in December 2012.

Lady Bird Johnson: An Oral History consists of three concurrent tracks. The first track presents her perceptive observations of life in two capital cities during a span of four decades. As a witness-participant, she vividly describes the events and personalities that shaped our world. The second track is the phenomenal political rise of Lyndon Johnson through a combination of good fortune, consummate political skill and resourcefulness, and incredibly hard work. The third and most compelling track is the transformation of a shy Southern country girl into one of the most admired and respected first ladies in American history.

If the picturesque rural setting of her youth fostered a love of natural beauty, her isolation also imposed self-reliance and a love of reading. There simply wasn’t much else to do. Her education was pivotal to her transformation. Two years at St. Mary’s College in Dallas instilled an appreciation of the English language, a measure of independence, and an enduring religious faith. Next came her four years at the University of Texas, which brought not only academic rigor, but also an active social life that she had never enjoyed before. In Austin she became more confident, more aggressive, and more willing to extend herself.

But a glimpse of Claudia Taylor’s life in mid-1934 suggests that something is missing. She is smart, intellectually curious, and shy but popular with many friends in Austin. Although she is not beautiful, her charm and appealing presence make her attractive to a succession of college beaus. She has just graduated with her second degree, majoring in Journalism. She has also earned a secondary teaching certificate, but she seems to view teaching as an opportunity to travel to exotic places rather than a vocation. She has also taken typing and shorthand courses so that she can, if necessary, secure a job as a secretary.

And yet she has no real plans for her future. Instead of pursuing a career, she takes a graduation trip to New York and Washington and then moves back to Karnack to spend a year remodeling the Brick House for her father. Her plan is, in her words, just “to see where fate led me,” as if she were a mere spectator of her own life. What is missing here is ambition; ambition that gives drive, direction, and purpose to life.

But Lady Bird’s life dramatically changes on September 5, 1934, with a chance encounter while she is visiting her friend Gene Boehringer in the state capitol. Suddenly, a young man named Lyndon Johnson walks in. He asks her to have breakfast the next morning. After breakfast and a day-long drive around the hills of Austin, he asks her to marry him.

The introduction of this powerful, unexpected force creates a terrible dilemma for Claudia Taylor. She is pressured to make the most important decision of her life within a span of less than three months. She barely knows the young man, and the fact that he is 1,200 miles away during most of their brief courtship makes it difficult to become better acquainted. But she must agree to marry this young man and move to Washington, or he will drop out of her life forever as quickly as he entered it. Her fear of losing him ultimately prevails over her innate caution.

If opposites attract, one can easily imagine that there was, as she described, “something electric going on” when they first met. The two were strikingly different in many ways. She was conservative, cautious, and judicious; he was liberal, impulsive, and always in a hurry. Her calm, gracious, shy demeanor contrasted with his expansive, demanding, volatile temperament. If she was thrifty, he was given to acts of extravagant generosity. She was essentially private and self-reliant, while he desperately needed people around him. She was a studious reader of books; he was at heart a teacher whose text was experience.

But what did she see in Lyndon Johnson? It was his drive, his forcefulness, his raw, honest ambition to which she was attracted. As she wrote during their courtship, “I adore you for being so ambitious and dynamic.” He gave her what she was missing; he shared with her his ambition, his sense of purpose.

The man whom Mrs. Johnson characterized as “a regular Henry Higgins,” contributed to her transformation in two ways. First, he “stretched” her, as he did everyone around him, challenging her to do more than she thought possible. At his urging, she extended herself to speak in public, to run the congressional office in his absence, to manage a radio station, and to renovate the dilapidated LBJ Ranch. His increasing confidence in her day after day, year after year, spurred her on. He also facilitated her growth by placing her in the daily company of intelligent, sophisticated women and men in Washington during the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, as she phrased it, “the society he thrust me into.” She attended and hosted countless teas and dinners for some of the nation’s most informed and interesting personalities, among them: George Marshall, Eleanor Roosevelt, Lady Astor, Tommy Corcoran, Marjorie Merriweather Post, Anna Rosenberg Hoffman, Paul Porter, Oveta Culp Hobby, and Josephine Forrestal. Through the Congressional Club for spouses, the Seventy-fifth and Eighty-first clubs, the Senate Ladies Club, and the Texas establishment in Washington, she participated in an extraordinary, continuing salon for almost thirty years before entering the White House.

The more Lady Bird Johnson changed and grew, the more she influenced LBJ’s life and his fortunes in a high-pressure profession. Her husband reaped the benefits of her warmth and grace as a hostess. Sam Rayburn, Dick Russell, and others who were instrumental in advancing LBJ’s career frequently enjoyed informal dinners in the Johnson home. And as Lady Bird Johnson’s political involvement and sophistication grew, her role in her husband’s rise to power expanded. Throughout his career, her good judgment and soothing comfort kept him on an even keel, while mending fences that he had damaged. Although she was virtually excluded from his first campaign for Congress in 1937, she became increasingly active in each of his successive races, and, by 1948, her role in the 87-vote cliff-hanger against Coke Stevenson was pivotal. When a kidney stone attack immobilized LBJ and he was on the verge of withdrawing from the race, she spirited him away to the Mayo Clinic, while keeping him from the press. She overcame her fear of public speaking to campaign for him throughout the state in the run-off. Finally, in the 1964 Presidential campaign, she rode the Lady Bird Special train through the South to become the first First Lady to campaign independently for her husband.

An apprenticeship as a congressional wife, a Senate wife, and as a frequent stand-in for Jacqueline Kennedy during the Vice Presidential years made Lady Bird Johnson one of the best prepared First Ladies ever to enter the White House. Her experience and skill served her well during the tumultuous 1960s. She assembled a professional staff in the East Wing of the White House and mobilized legions of influential, resourceful women and men to beautify and conserve the nation’s environment. With Washington, DC as their initial focus, they created a spectacular showcase for millions of American tourists could see what was possible in their own hometowns. Next she traveled through the country to draw attention to its scenic beauty and the threats to the nation’s environment. To her, beautification was just one thread in the larger tapestry of clean air and water, green spaces and urban parks, scenic highways and country side, cultural heritage tourism, and significant additions to our system of national parks.

Lady Bird Johnson’s environmental leadership was only one facet of her remarkable legacy as first lady. She also continued her predecessor’s quest for authentic furnishings and important American art for the White House. She recognized the achievements of women with her Women Doers Luncheons. Embracing the Head Start program, she gave it the prominence of a White House launch.

She participated gracefully in an endless succession of presidential trips, state dinners, congressional receptions, and other social events, including two White House weddings. At the same time, she provided LBJ with, in her words, “an island of peace” throughout his heady, turbulent presidency. Finally, she bequeathed to posterity an historical legacy: her White House diary of more than 1,750,000 words and forty-seven oral history interviews, comprising almost another half-million words.

Michael L. Gillette, Lady Bird Johnson: An Oral History

You might also enjoy:

Michael L. Gillette, Liz Carpenter: Texan

Related links:

Dear Bird: The Courtship Letters

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

Lady Bird Johnson at the LBJ Library and Museum

The Fastest Courtship in the West, from The Vault, Slate’s History Blog

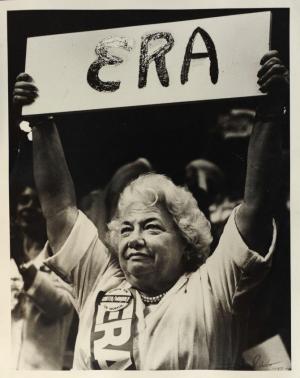

Another great aunt, the prominent suffragist, Birdie Johnson, became the first Democratic national committeewoman from Texas. As she exhorted women to organize to make their influence felt at the polls, she declared that it was “our first step” in the exercise of “direct political power.” No wonder Liz believed that she had inherited her feminist genes.

Another great aunt, the prominent suffragist, Birdie Johnson, became the first Democratic national committeewoman from Texas. As she exhorted women to organize to make their influence felt at the polls, she declared that it was “our first step” in the exercise of “direct political power.” No wonder Liz believed that she had inherited her feminist genes. It also instilled a love of Texas history and a respect for its historians, which is why

It also instilled a love of Texas history and a respect for its historians, which is why  When Liz made a courtesy call on her congressman, she discovered that his wife was running the office while he was overseas. It was that visit that introduced Liz Carpenter to

When Liz made a courtesy call on her congressman, she discovered that his wife was running the office while he was overseas. It was that visit that introduced Liz Carpenter to

Clark and Libbie Moody Thompson entertained Texans so often that their elegant home became known as the Texas Embassy. And on countless Sundays, the four Carpenters–Liz, Les, Scott, and Christy—would spend the afternoons, at the Johnson home with Speaker Rayburn, other members of Texas congressional delegation, and the Texas press and their families. The topic of discussion was always politics. What an extraordinary postgraduate education these afternoons must have been!

Clark and Libbie Moody Thompson entertained Texans so often that their elegant home became known as the Texas Embassy. And on countless Sundays, the four Carpenters–Liz, Les, Scott, and Christy—would spend the afternoons, at the Johnson home with Speaker Rayburn, other members of Texas congressional delegation, and the Texas press and their families. The topic of discussion was always politics. What an extraordinary postgraduate education these afternoons must have been!