Millions of tweets and millions of state documents. Intimate oral histories and international radio addresses. Ancient pottery and yesterday’s memes. Historians have access to this immense store of online material for doing research, but what else can we do with it? In Spring 2018, graduate students in the Public and Digital History Seminar at UT Austin experimented with ways to make interesting archival materials available and useful to the public; to anyone with access to a computer. Over the Summer, Not Even Past will feature each of these individual projects.

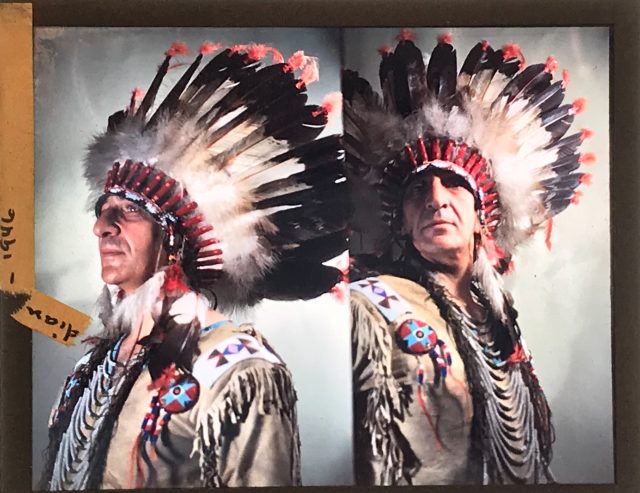

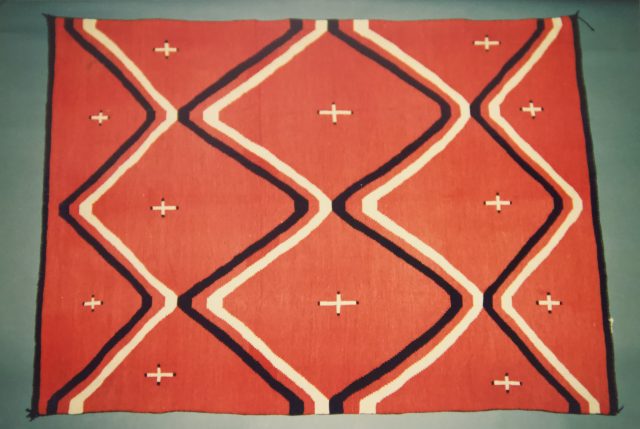

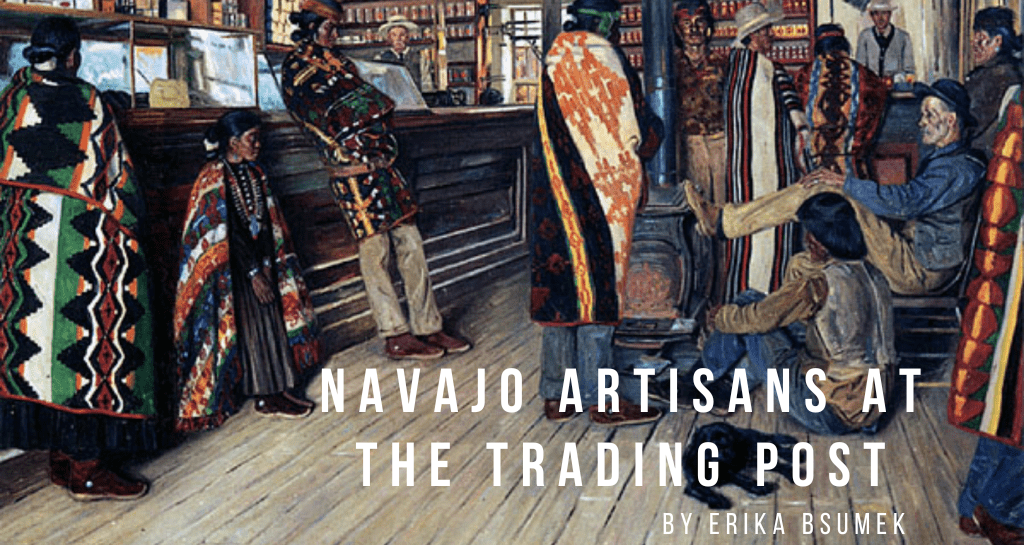

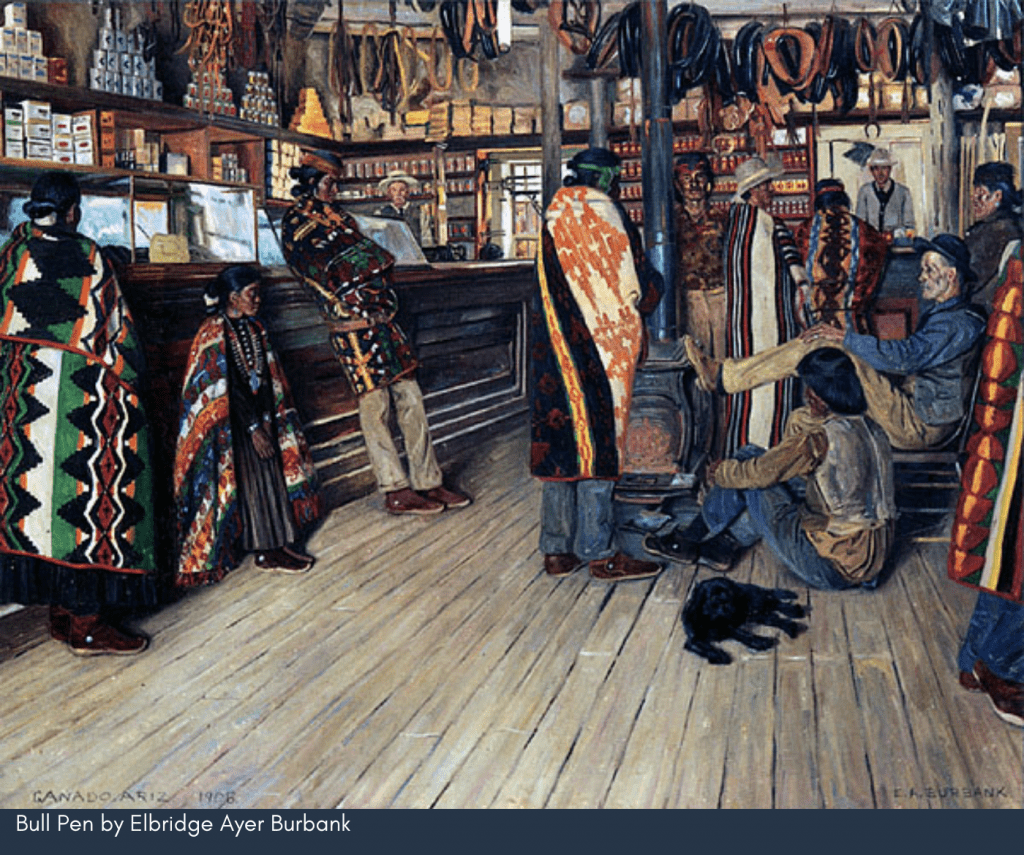

Alina Scott‘s project, titled Woven into History, is a digitized collection of nineteenth and twentieth-century Navajo rugs currently on exhibit at the Blanton Museum of Art. In addition to photographs of the rugs themselves, Woven into History also provides a brief history of the Navajo and lesson plans to contextualize the collection and provide a platform for respectful collaboration and discussion.

More on Scott’s project and the Public Archive here.

Also by Alina Scott on Not Even Past:

Cynthia Attaquin and a Wampanoag Network of Petitioners

Missing Signatures: The Archives at First Glance

You may also like:

A Historian’s Gaze: Women, Law, and the Colonial Archives in Singapore by Sandy Chang

Secrecy and Bureaucratic Distancing: Tracing Complaints through the Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive by Vasken Markarian

Justin Heath reviews Peace Came in the Form of a Woman by Juliana Barr (2007)