It was the most intense intellectual and political love story that modern Arab intellectuals had ever had with a living European thinker and – even better – the sentiment was mutual. From the late 1940s to the late 1960s, Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophy, and his political recipes for self-emancipation, guided the project of Arab liberation. From the very beginning, Middle Eastern intellectuals considered Sartre’s ideas rich, meaningful and appropriate for their needs. Their goal was ambitious: the invention of a new type of Arab man and woman: sovereign, authentic, self-confident, self-sufficient, proud, willing to sacrifice and therefore, existentially free. Tampering with existence was their key strategy for a smooth exit from the legacy of colonial dehumanization, and Sartre’s intellectual fingerprints were all over this strategy. By the late 1950s the Arab world could boast of having the largest existentialist scene outside Europe. Indeed, almost everything that Sartre said and wrote during these years was translated to Arabic as soon as it hit the French market.

Sartre too was infatuated. Frustrated with European political passivity of the 1960s, he was enchanted by the sheer energy and broad horizons of the Arab revolutionary project. At the peak of this affair, Sartre and his home-made diplomatic crew came, in person, to pay respect to the Arab revolutionary project. And for a brief moment, the alliance appeared to be indestructible. And yet, for all the high philosophical talk about existence and revolution, the affair ended bitterly and Sartre would be forever remembered as a traitor to the Arab cause. Not just a traitor but one of the worst kind: a former friend. Here is a brief account of this painful trans-Mediterranean affair, its promise, and its demise

As World War II drew to a close and colonialism was in full retreat, a small but influential circle of Arab philosophers identified the sphere of being as the most intellectually significant problem to reckon with. What does it mean to be a person after colonialism? After decades during which Arabs were struggling objects in the closed world of European consciousness, who and what dominated the definition of the self and the political community to which it belonged? To answer this question and produce ideal conditions for cultural rejuvenation, they turned to philosophy and, specifically, to phenomenology and its new branch, existentialism. Studying with the very best teachers Europe could offer, they slowly learned that the essence of their colonized being was not fixed. That is, that the Left Bank slogan of Parisian youth, “existence precedes essence,” carries a very special promise of liberation. They realized that their struggle to become free and modern had nothing to do with the purported “essence” of an Islam framed as antithetical to reason, science, democracy and individualism.

Rather, it was a simple relational issue. Just as existentialism made Simone de Beauvoir realize that “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” it made colonized people understand the very process that made them inherently and irredeemably inferior. Existentialism not only exposed the paradoxical impossibility of the colonial demand but also offered tools to transcend it through self-liberation. The groundwork had already been laid a few years beforehand, as young philosophers had labored over how Islamic mysticism could be reconciled with Heidegger’s philosophy of being for the sake of creating an authentic and free individual. When Sartre’s work arrived to the Middle East it interfaced with this already-established philosophical opportunity, perfecting and substantiating it in simple and actionable ways.

The first such attempt was to generate a local version of Sartre’s idea of commitment, or engagement. According to Sartre, because writing is a consequential form of acting and being, intellectuals must assume political responsibility for their work and the circumstances that condition it. That meant that old guard intellectuals who were comfortable with the cultural assumptions of colonialism should be marginalized and retired. In their place, a new cadre of writers began the tedious work of intellectual decolonization. Known in Arabic as iltizam, this call for responsibility joined to professional action reorganized the cultural sphere and came to determine the political viability and legitimacy of any new idea. It also launched the careers of young thinkers, destroyed those of the established intellectual guard and established the norm that in decolonization culture and politics are inseparable.

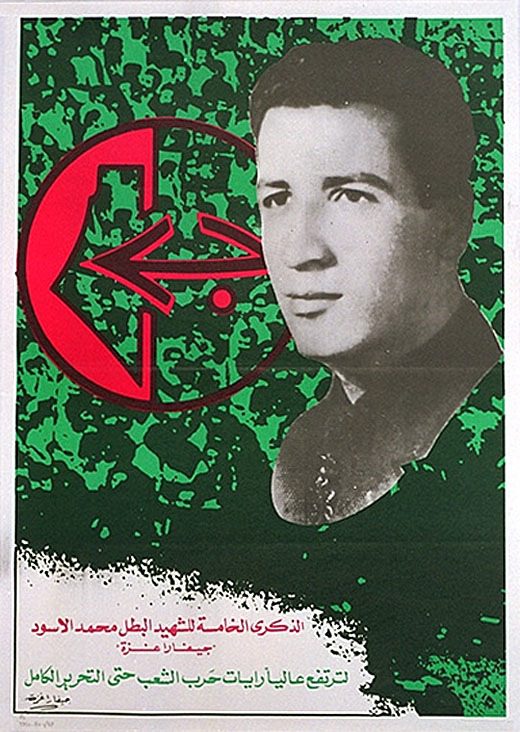

Most influential, however, was Arab intellectuals’ engagement with Sartre’s anti-colonial humanism, a cluster of thought that meaningfully connected the Arab world to Third-Worldism and the big struggles of the 1960s. This body of thought was shared by Sartre, Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and many other, lesser-known intellectuals from the former colonies. Together, these intellectuals developed the foundations of post-colonial thinking about race and otherness as well as concrete concepts such as settler colonialism and neo-colonialism. These were not simply ideas but politics that translated to specific struggles for liberation in Cuba, Congo, Vietnam, Rhodesia and of course Algeria. It is the same body of thought that would eventually connect seemingly unrelated struggles such as those of the Black Panthers in the US with the revolutionary politics of Algerian freedom fighters. Today we call this intersectionality. Back then, there were no fancy words to describe the daily business of the Global South. Being the first global thinker to engage international politics on that level, Sartre was intellectually involved in all of these struggles. He readily acknowledged the oppression to which colonized people were subjected and his thought paved the way for self-liberation. The ultimate destination was global citizenship. In the service of this goal, Sartre weaponized ideas and mobilized metropolitan public opinion on behalf of all of these struggles.

That is, all of them except one – Palestine. Sartre’s silence on the conflict in Palestine mystified his Arab interlocutors. How could the person who contributed to the intellectual DNA of Arab decolonization – who had explained to them in no uncertain terms that they are the “collective others” of colonialism – not see that Zionists in Palestine were doing the exact same thing as French colonizers in Algeria and British ones in Rhodesia? What was unclear here? Was Sartre a crypto-Zionist? How could he turn his back on his own intellectual legacy to make such an exception? The truth of the matter was that Sartre’s political paralysis was due to an irresolvable philosophical conundrum. Yes, he was one of the first thinkers to reckon otherness and translate oppression into viable ethical frameworks that were clear and actionable. That was the basis for his position on Algeria, by which he went against his own motherland, and it was the basis for his support for anti-colonial violence. He could certainly see and recognize Arabs as the “Others” of colonialism and even of Palestinians as the victimized “Others” of Zionism. However, he had no idea how to reconcile two “others” that existed in the case of Palestine. Who was right? Who deserved what, and on which ethical ground? Who was a greater victim? Sartre could not resolve this question and the fact that his own society was instrumental in the destruction of European Jews did not help, either. Indeed, Arabs began to suspect that he was trading in ethical reparations for Zionists.

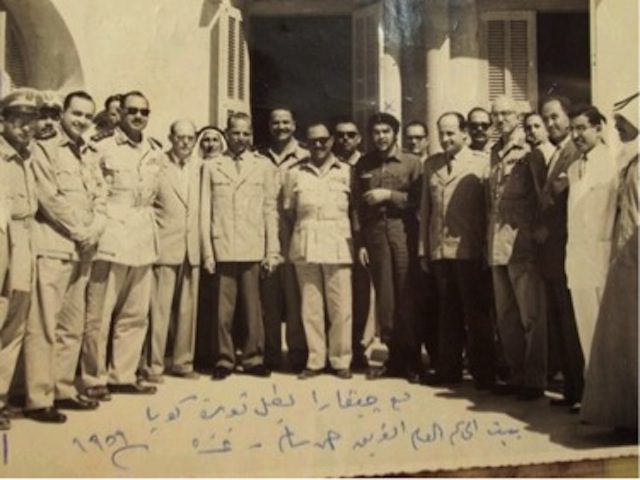

Responding to Arab and Israeli pressures to clarify his position (that is, to declare once and for all who was “right”), Sartre decided to visit Egypt, Gaza, and Israel. He did so on the late-night eve of the 1967 war, a war that would forever destroy the Arab project of liberation. The visit went relatively well, with both sides respecting Sartre’s request for time and space in order to formulate and then publish his opinion. The Israeli press called Sartre the philosopher of the Arabs and knew fairly well how instrumental he was for their liberation project. The Arab side suspected he was pro-Zionist but had no proof of it. For his part, Sartre was simply confused. As the visit ended and the chain-smoking philosopher returned to his Parisian apartment to write down his thoughts on the conflict, a full-scale Arab-Israeli war was already in the air. In the weeks prior to it, the general sense in Europe was that Israel would be forever destroyed. Sartre’s Jewish friends and their many acquaintances on the Left asked him to support their cause and avoid a so-called “second Holocaust.” He was reluctant to do so. After more pressure, he finally relented and, on the eve of the war, signed a petition on behalf of Israel. The who’s who of French culture, from Picasso to Marguerite Duras, signed the petition. His Arab interlocutors were stunned. But before they could even organize themselves to protest this signature, the war came, and destroyed everything for which they had struggled. Their project was in ruins, and Sartre was forever implicated in the most significant Arab defeat of modern times. So began, and so ended, a passionate intellectual and political affair, founded in visions of total freedom and concluded in heartache and infamy.

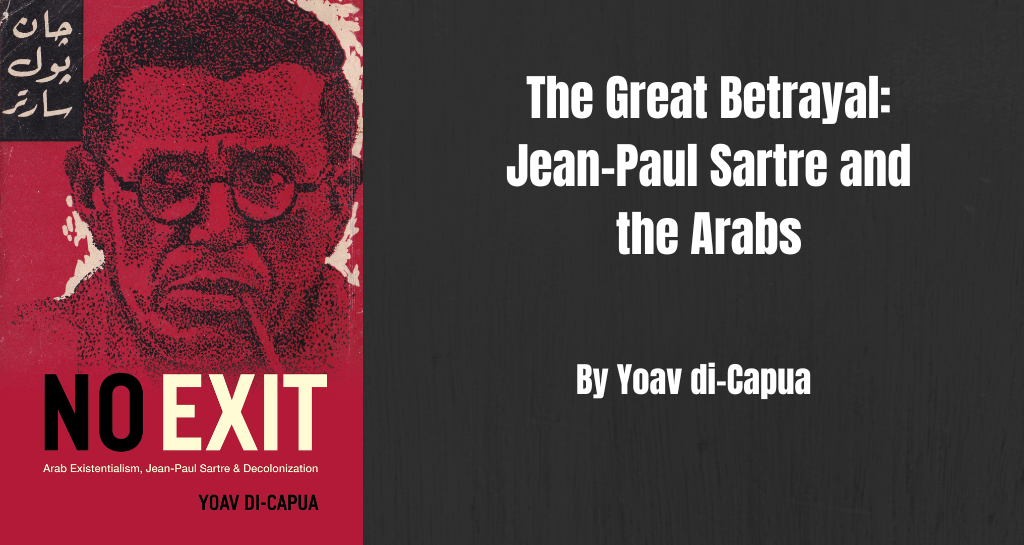

Yoav di Capua, No Exit: Arab Existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre and Decolonization

Read more about existentialism and Arab history:

Sarah Bakewell, At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails (2016)

Ever wondered what was the existentialist hype all about but was never quite able to make sense of it? Give it another chance with Sarah Bakewell’s entertaining, engaging and highly lucid exploration of the philosophy and the people behind it. Voted one of the best books of 2016, At the Existentialist Café is a rare intellectual accomplishment that sets a new standard for popular intellectual history.

Eugene Rogan, The Arabs: A History (2009)

This international bestseller offers the most updated and fluent history of the modern Arab world. Rogan makes the daunting task of making sense of the last two centuries of Arab history much less intimidating and complex than initially assumed. Crucial reading for those who wish to quickly understand this foreign land and bring themselves up to date with the history of a people who is more often than not misunderstood.