On January 2, 1959, Fidel Castro, the rebel comandante who had just overthrown Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, addressed a crowd of jubilant supporters. Recalling the failed popular uprisings of past decades, Castro assured them that this time “the real Revolution” had arrived. Castro’s words proved prophetic not only for his countrymen but for Latin America and the wider world.

The political turmoil that rocked a small Caribbean nation in the 1950s became one of the twentieth century’s most transformative events. Initially, Castro’s revolution augured well for democratic reform movements then gaining traction in Latin America. But what had begun promisingly veered off course as Castro took a heavy hand in efforts to centralize Cuba’s economy and stamp out private enterprise. Embracing the Soviet Union as an ally, Castro and his lieutenants, Che Guevara and Raúl Castro, sought to export the socialist revolution abroad through armed insurrection. Chairman Khrushchev’s early support aided the Cuban revolutionaries in defeating of the CIA invasion of Cuban émigré fighters at the Bay of Pigs. However, he subsequently lost his job over the 1962 Missile Crisis that pushed the superpowers to the brink of nuclear war.

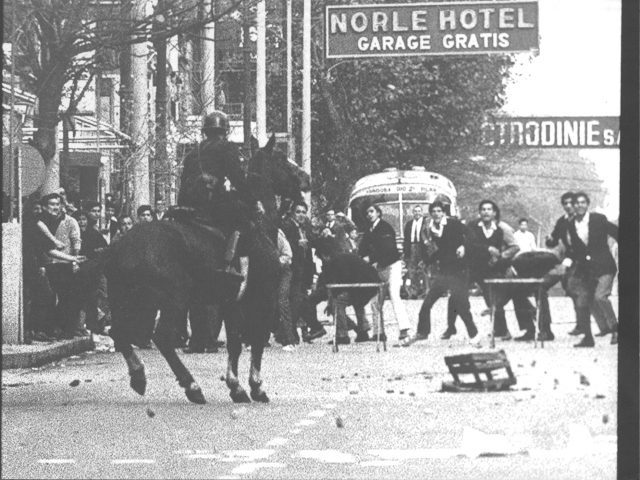

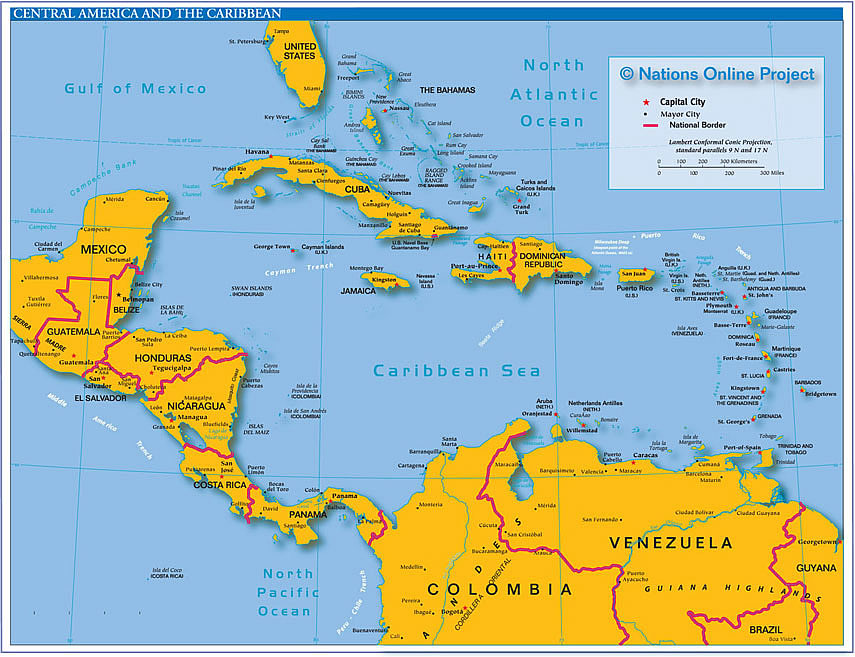

By the end of the 1960s, rural and urban uprisings linked to the Cuban Revolution had spilled over from Central America into the bigger countries of South America. Revolutionary groups whose leaders had trained in Havana were operating in Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina. Most of the rural and urban guerrillas may not have traveled to Cuba. Yet they certainly followed Fidel’s “anti-imperialist” example. Che himself attempted to spread the revolution to Bolivia, where he died. Other rebel groups with names such as the Tupamaros and Montoneros and still others with initials like FALN, ELN, and MIR defined the 1960s as the age of student unrest.

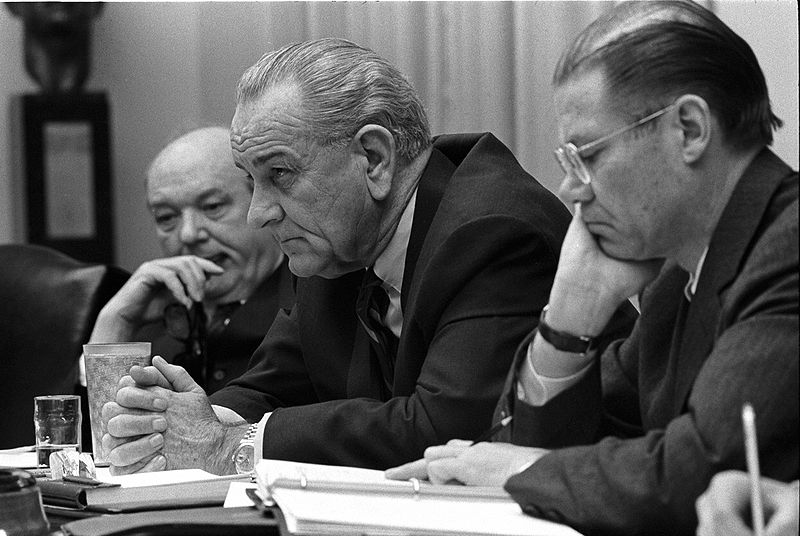

Castro’s provocations inspired intense opposition. Cuban anti-communists who had fled to Miami found a patron in the CIA, which actively supported their efforts to topple Castro’s regime. American presidents supported anti-communist forces that often utilized disproportionate violence against pro-Cuban dissidence in their own countries. The insurrections fomented by leftist guerrillas lent support to Latin America’s military castes, who promised to restore stability. Brazil was the first to succumb to a coup in 1964. A decade later, juntas of generals governed most Spanish and Portuguese-speaking nations of the Western Hemisphere. Rightwing terror claimed increasing numbers of casualties into the 1980s. Thus did a revolution that had seemed to signal the death knell of dictatorship in Latin America produce its tragic opposite.

Latin America’s military establishments especially came to oppose revolution because they learned what had happened to the Cuban army that failed to defeat Castro’s guerrilla rebellion. Revolutionary firing squads killed hundreds of military and police officers when the Batista dictatorship fell. Consequently, Che Guevara’s travels in Latin America proved especially toxic. President Jânio Quadros of Brazil resigned one week after presenting Guevara with a medal and Argentina’s army generals deposed President Arturo Frondizi several months after he “secretly” met with El Che.

However, it is instructive that two generals who performed coups d’état in 1968 took advantage of the nationalist feelings of peasants and workers to establish pro-Cuban juntas. Generals Juan Velasco of Peru and Omar Torrijos of Panama ousted elected governments in order to implement overdue social reforms. Many countries of Latin America followed the Brazilian example of establishing long-term counterrevolutionary military dictatorships. Brazil’s generals governed for twenty-one years.

The Cold War that Cuba introduced to Latin America affected the lives of countless ordinary citizens. Humberto Sorí Marín, the revolution’s first agriculture minister. opposed the turn toward communism, resigned, and fled to Miami, only to return with a cache of weapons for an uprising against Castro. He died before a firing squad. There was also Osvaldo Ramírez, the bandit king of the Escambray Mountains who led a widespread guerrilla rebellion against Castro’s rule until militia troops shot and killed him in battle. His anti-communist guerrilla successors endured within Cuba until 1965.

Antonio “Tony” Zamora was one Castro opponent who survived. He aspired to study law but left Cuba in 1960 to join the brigade of exiled Cuban youths who landed at the Bay of Pigs. President Kennedy ransomed Zamora and his fellow prisoners following the Cuban Missile Crisis. Tony became a lawyer in Miami and went on to advocate greater dialog with the Castro regime as the Cuban Revolution approached its fiftieth anniversary.

Cuba’s revolution attracted youthful visitors from all over Latin America who wished to learn how they too might become armed revolutionaries. Julio García left the University of Buenos Aires to learn how to fight as a guerrilla in 1962. However, he and several other Argentineans quit the camps after training became too rigorous for them. Venezuelans like Luben Petkoff did finish Cuban guerrilla training. Luben engaged in combat for nearly ten years only to give up finally with a pardon from one of the few democracies that survived the 1960s.

Women too became involved in the turmoil. The guerrilla Tania gave up her life for the revolution, this one in Bolivia. Tania’s real name was Tamara Bunke Bider, an Argentinean-born East German who first met Che Guevara as a government translator in East Berlin. She immigrated to Cuba in the early 1960s and eventually became Che’s spy in La Paz, Bolivia. Tania campaigned with Guevara’s last guerrilla group in 1967 and suffered the fate of most of his followers.

Argentina’s Norma Arrostita visited Havana in 1967 to attend a conference of armed leftists from all over Latin America. When she returned to Buenos Aires, Norma acted as the lookout for the kidnapping and killing of a former general who once served as Argentina’s president. A founding member of the urban guerrilla group known as the Montoneros, Arrostita later “disappeared” in a military prison like thousands of other suspected radicals.

As Mao used to say, “The revolution is not a dinner party.” Fidel Castro provided the corollary. “But the counterrevolution” he said, “is always more cruel.”

Jonathan C. Brown, Cuba’s Revolutionary World (2017)

For more on twentieth-century Latin American revolutions, try these:

Jorge I. Domínguez, Cuba: Order and Revolution (1978).

The foundational text for any serious study of Cuba’s three revolutions in the modern age: the Wars of Independence, the 1933 Revolution and rise of Fulgencio Batista, and the 1959 Revolution of Fidel Castro and his many associates.

Alexandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964 (1997).

A fascinating account of Havana-Moscow relations culminating in the October Missile Crisis of 1962. The authors had access to Soviet and US document collections but only a few Cuban ones, which are generally not available to researchers. The title derives from a statement by President Kennedy during a White House discussion about Premier Khrushchev’s possible motivations for placing nuclear missiles in Cuba.

Jan Lust, Lucha revolucionaria: Perú, 1958-1967 (2013).

The most thorough study of a guerrilla movement in any country of Latin America during the 1960s. The author interviewed survivors and collected detailed information on leaders and fighters from a variety of sources.

Valeria Manzano, The Age of Youth in Argentina: Culture, Politics, and Sexuality from Perón to Videla (2014).

An important study of the student movements of one important country in South America during an age of youthful protests and cultural change wrought by national political turmoil and military interventions. The book covers the period from the 1955 overthrow of Juan Perón to the 1976 coup d’état that preceded the last military dictatorship of the country.

You might also like:

Articles on Cuba on Not Even Past

Jonathan C. Brown, Che Guevara’s Last Interview

Rebecca Johnston, The Man Who Loved Dogs by Leonardo Padura