More on the Kiowa from our featured author of the month.

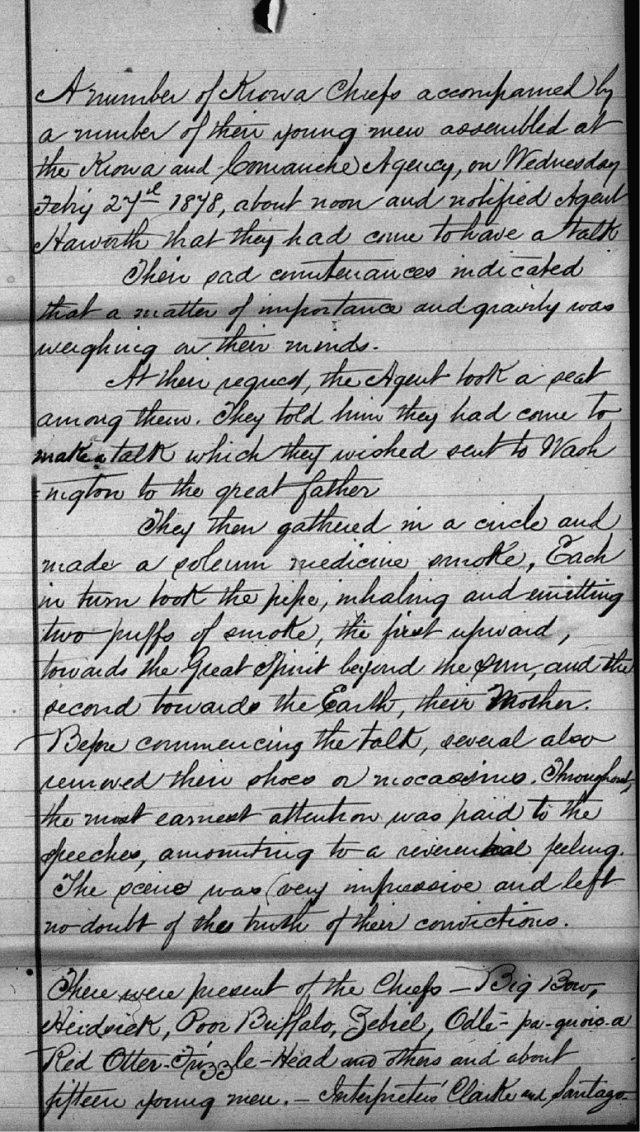

In 1890, a strange letter with “hieroglyphic script” arrived at Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School. It was sent from a reservation in the Oklahoma Territory to a Kiowa student named Belo Cozad. Cozad, who did not read or write in English, was able to understand the letter’s contents—namely, its symbols that offered an update about his family. The letter provided news about relatives’ health and employment, as well as details about religious practice on the reservation.

Letter written using Kiowa sign language. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

While Belo Cozad understood the letter, Americans working at the school did not. Neither did reservation officials who saw the letter once Cozad returned to Oklahoma. Anthropologists working there sent a copy to the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology, where a staff member set out to understand it. Interviewed back on the reservation, Cozad provided “translations” of the letter. The anthropologists concluded that several Kiowas, though hardly all, knew this writing system. Although Cozad insisted that his parents and grandparents had long known the practice and taught it to him, the specialists concluded that it was of “recent origin.”

Letter written using Kiowa sign language. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

The anthropologists were partly right. The system had only recently been put on paper. But the gestures and signs that inspired it, recently labeled by non-Natives as Plains Indian Sign Language, had been used by Kiowas for generations. Indeed, one of the Smithsonian workers likely recognized it from earlier work on Native signing systems. The marks on Cozad’s letter mimicked the signs for individual words. A circle followed by four loops signifies four brothers. Three horizontal lines stand for the number three. A box with vertical lines, followed by a swooping downward and then upward line, means that someone has been buried in a grave. Together, the signs tell Cozad that he no longer had four brothers, but only three. One had recently died and been buried.

Symbols relating the death and burial of Cozad’s brother. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

With this letter, Cozad’s family took an old form, Plains Indian Sign Language, and adapted it for their new situation. With the hope of reaching their kin in boarding school, they had put signs onto paper and placed it in the US mail.

Kiowas displayed a similar capacity to adapt older forms from the realm of religious practice. Ritual gatherings, especially their version of the Plains Indian Sun Dance, were threatened by declining buffalo herds and, eventually, military supervision and criminalization. Even so, Kiowas found ways to adapt their Sun Dance rites to new conditions, including purchasing buffalo hides from Texas ranchers and choosing ceremony sites far away from government supervision.

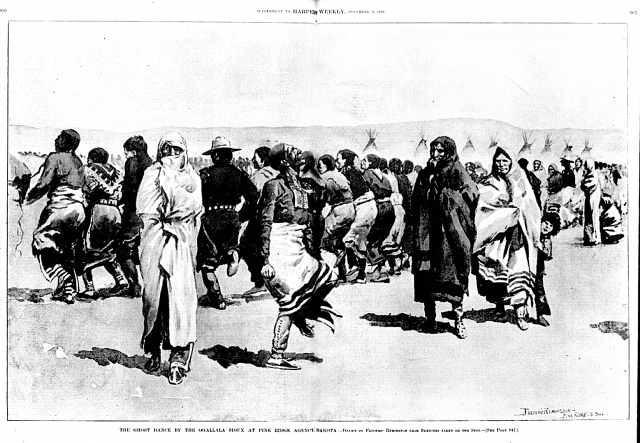

They also experimented with new sources of sacred power. Between 1868 and the end of the century, some Kiowas borrowed peyote rites from neighboring indigenous peoples. Soon, Kiowas developed their own peyote songs and added peyote to the pantheon of beings and things imbued with power. Other Kiowas accepted the message of Wovoka, the Paiute leader of the movement that came to be known as the Ghost Dance. They danced with the expectation that relatives who had died and depleted buffalo herds would be restored. Still others considered Christian missionaries’ proclamation about Jesus as a powerful figure who provided healing in this life and heaven in the next.

Kiowa ritual life followed a pattern recognizable in the Cozad’s sign language letter, namely the adaptations of older forms for new and difficult situations. For generations, Kiowas had gathered to seek blessing, protection, healing, and empowerment from beings imbued with dwdw, or sacred power. At Sun Dances, these efforts focused on the sun and the buffalo. In other venues, Kiowas sought visions and healing that could be bestowed from powerful animals, plants, or places. Often, Kiowas presented offerings as they made supplications, or to signal their thankfulness when blessings were received.

In their letters, Cozad’s family took the long-practiced gestures of sign language and sent them across the hundreds of miles that separated the reservation and boarding school. Kiowa religious life exhibited a similar pattern. For the sake of connecting family and maintaining land in a desperate colonial situation, Kiowas sought new ways to engage sacred power. Even as they looked to new sources, they maintained the postures of supplication, the same tokens of thanks. Cozad’s letter included references to these new practices. The writers tell Cozad, through signs, that Jesus is looking down over all the tipis and beyond in the four cardinal directions.

Symbols show Jesus looking over the Native Americans. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

The relatives encourage Cozad to pray to Jesus. They also signal the diversity of religious forms among Kiowa people. At the letter’s end, through signs that stand for the moon and the morning star, the family relates that a fellow Kiowa has been out singing peyote songs.

Symbols relate how one Kiowa experimented with peyote rites. Used by permission from Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

In a period of unwelcome and devastating change, Kiowas did new things. They tried peyote rites and Christian prayer. They wrote letters and put them in the US mail. But all these things reflected older ways of being and doing. And all these things functioned to maintain family, kin, nation, and land in an increasingly perilous situation.

This article originally appeared on the OUPblog, May 9, 2018.