On a research trip last summer, I found a previously unidentified thirteenth-century manuscript in a library in Poznan, Poland, and recognized that it contains the writings of a late twelfth-century monk named Engelhard of Langheim. One of the Latin texts in this manuscript is the saintly biography of a religious woman named Mechtilde of Diessen. The following story, found only in this one Polish manuscript, appears as a postscript:

Saint Mechtilde, as was said earlier, was in the habit of writing. She did so to avoid eating the bread of leisure, and in this especially she believed she greatly pleased her God. She frequently brooded like a mother hen over the writing of missals and psalters because she thought – or rather she hoped – to serve the divine more earnestly in doing this. Her hope did not betray her. For one day, when she still had work remaining, she wished to repair a blunt pen, but she did not succeed. The pen was very troublesome to prepare. She was knowledgeable about cutting quills, but once cut, this quill did not respond when tested. This caused in her not a little disturbance of her spirit. “Oh,” she said, “if God would only send me his messenger, who could prepare this pen for me, for I have rarely suffered this difficulty, and it is now greatly troubling me.” As soon as she said this, a youth appeared. He had a beautiful face, a shining robe, and sweet speech. He said, “What troubles you, O beloved?” And she said, “I spend my time uselessly, I toil for nothing, and I do not know how to prepare my pen.” He said, “Give it to me, and perhaps you will not be hindered anymore by this knowledge when you wish to prepare it.” She gave it to him, and he prepared it in such a way that it remained satisfactory for her until her death: she wrote with it for the many years that she lived. After this miracle, when she spent time writing, no one could write so well, no one so quickly, no one so readily, and no one so correctly, nor could anyone imitate in likeness her hand. The pen’s preparation, as I said, was permanent, but the preparer disappeared and appeared in the work of which he was the maker. I have reported this just as the daughter of the duke of Merania, herself a holy virgin, has testified. She, reading this little work on the life of Mechtilde, asked to add what was missing.[1]

This brief little anecdote tells us a great deal about the literacy of medieval nuns. First, it reminds us that nuns as well as monks copied manuscripts. In recent years, our understanding of medieval literacy has become more nuanced. Scholars have separated the ability to read, to write, and to compose texts into discrete aspects of what we now call “literacy.” We know that many nuns and many aristocratic women could read: noble women in the later middle ages commissioned elaborate prayer books called Books of Hours, mothers were pictured reading to their daughters, and convents sometimes had extensive libraries. We also know women composed texts, but they often did so with the cooperation of male scribes who wrote down what the women dictated. Female scribes, however, are hard to locate. Scribes did not always sign their names to their work, and women may have been particularly reticent to do so. But we are beginning to realize that writing was a form of work for nuns as well as for monks and that, at times, religious men and women even worked together to produce manuscripts. Monks also sent drafts of their compositions to nuns to be copied. As one twelfth-century monk told the abbess of a convent, “having no scribe at my disposal, as you can see by the irregular formation of the letters, I wrote this book with my own hand.” As a result, he asked to have his text “copied legibly and carefully corrected by some of your sisters trained for this kind of work.”[2]

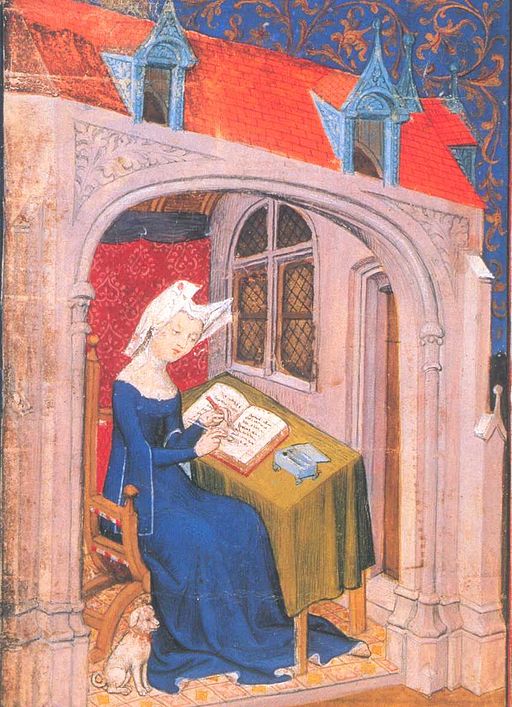

This is a 15th century image of Christine de Pisan (1363 – c. 1430), one of the best known authors of medieval Europe. She is shown writing her own book, but she is using the same tools that Mechtilde would have employed: she has a pen in one hand and a scraper in the other

This is a 15th century image of Christine de Pisan (1363 – c. 1430), one of the best known authors of medieval Europe. She is shown writing her own book, but she is using the same tools that Mechtilde would have employed: she has a pen in one hand and a scraper in the other

Mechtilde probably did not copy texts that she herself composed. The story depicts writing as a form of spiritual labor that prevented a dangerous leisure: Mechtilde’s irritation that she wasted her time trying to fix her pen demonstrates her concern for purposeful work. But the content of the books still mattered.

A second interesting element of this story is that Mechtilde associated her careful copying of missals and psalters with serving God, a phrase more frequently used to describe the prayers and rituals that these texts depicted. The Psalms formed the fundamental prayers for monks and nuns; in praying six times a day and once at night, monks and nuns sang the entire psalter every week and repeated some Psalms daily. By copying psalters, Mechtilde could pray while she wrote. Copying missals, however, had a different implication, for the missal was the liturgical book for the mass. Mechtilde could not perform the mass, but the story suggests a parallel between her writing and the actions of a priest. Although Mechtilde asked God to send his messenger to assist her, the young man’s appearance and his reference to Mechtilde as his “beloved” suggest that he was Jesus. Just as a priest, using the prayers and instructions laid out in a missal, transformed the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, so Mechtilde, in copying missals with devotion, filled those books with the presence of Jesus: “he appeared in her work of which he was the maker.” As a woman, Mechtilde was unable to serve at the altar, but she had found another way to participate in the performance of the mass.

Finally, the transmission of the story is noteworthy. The author of Mechtilde’s life, the monk Engelhard of Langheim, never met Mechtilde, but he knew members of her family: they were important patrons of his monastery. In the saint’s life, Engelhard had mentioned briefly that Mechtilde was a scribe but he did so only to emphasize her willing obedience to put down her pen immediately when summoned. He learned the story about the pen from Mechtilde’s niece. The niece, a daughter of a duke, was also a nun, and she placed more emphasis on her aunt’s writing. Her memories of her aunt suggest that in the middle ages, as today, family histories were often the preserve of women and that tales were often recounted orally from one generation to the next. The niece’s story, as Engelhard recorded it, gives us a brief glimpse into the family legends of this one aristocratic lineage.

You may also enjoy

Martha G. Newman, A Medieval Vision

For more information on women as scribes and as readers, see

Alison Beach, Women as Scribes: Book Production and Monastic Reform in Twelfth-Century Bavaria (2004)

David N. Bell, What Nuns Read; Books and Libraries in Medieval English Nunneries (1995)

[1] Engelhard of Langheim, “De eo quod angelus ei pennan temperavit.” Posnan, Biblioteka Raczynskich. Rkp156, 117r-v.

[2] “A Dialogue between a Cluniac and a Cistercian” in Cistercians and Cluniacs: The Case for Cîteaux, trans. Jeremiah F. O’Sullivan (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1977), p. 22.

Photo Credit: Christine de Pisan, Wikimedia Commons

In Besieged: Voices from Delhi 1857, Mahmood Farooqui draws on more than ten thousand Urdu and Persian documents processed by the rebel administration and later used by the British as evidence in Bahadur Shah Zafar’s trial. As Farooqui notes in the introduction, despite the widespread availability of histories, memoires, and essays on the 1857 uprising, we know much about the British experience and remarkably little about what went on within the walls of the seized city. The documents in this collection show how the rebel government administered the city and how the uprising affected ordinary people.

In Besieged: Voices from Delhi 1857, Mahmood Farooqui draws on more than ten thousand Urdu and Persian documents processed by the rebel administration and later used by the British as evidence in Bahadur Shah Zafar’s trial. As Farooqui notes in the introduction, despite the widespread availability of histories, memoires, and essays on the 1857 uprising, we know much about the British experience and remarkably little about what went on within the walls of the seized city. The documents in this collection show how the rebel government administered the city and how the uprising affected ordinary people.